I had a depressing conversation with a friend in the music business the other day about how vinyl records are once again outselling CDs, even though most of us don't have turntables any more. It took us little more than 100 years to come full circle back to a place where the only way to make any money from music is by performing it live before paying customers.

Philosophically this makes sense. With YouTube, Spotify, Pandora and the like, consumers don't feel compelled to buy recorded music. When you can have access to millions of songs for a low monthly fee (or for free) it doesn't make much sense to maintain a home library. Instead of splurging at the record store, you can spend your disposable income going to shows (or on computer games).

Besides, listening to music played in real time is arguably a much more authentic experience than listening to a record that's been built track by track. Some people (Deadheads, Parrotheads) profess to prefer the live experience. A nerdy minority -- to which I belong -- tend to be more interested in the recorded product, which yields liner notes and cover art and sometimes a separate narrative as well as the music. This nerdy minority that places primacy on the physical manifestations of recorded music is aging out of the marketplace.

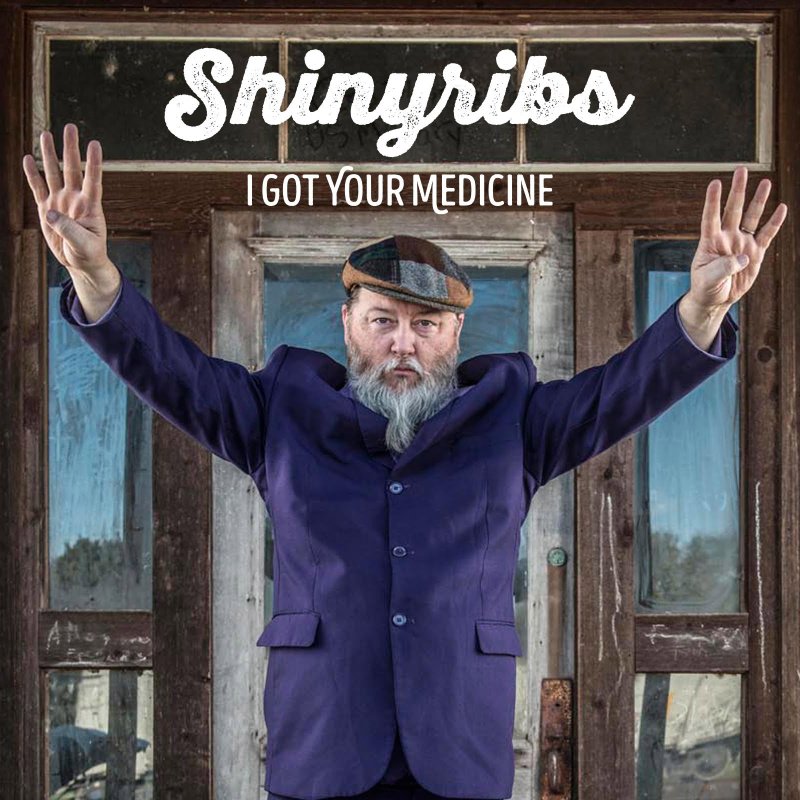

So the highest and best use of the new Shinyribs album I Got Your Medicine may be as a souvenir of a show, and the best way to buy it may be at a merch table while you're still drenched in dance sweat. But it may be a while before Shinyribs shows up at a venue near you.

I've been a fan of Kevin Russell for 35 years or so. He's one of those remarkable people who simply sweats music; it just pills up on him until he shakes it off. I've seen him go through several incarnations, from Picket Line Coyotes -- who should have been Shreveport's answer to The Replacements and Husker Du in the '80s -- to the folk-rock collective The Gourds, to his latest ever-evolving role as the leader and embodiment of Shinyribs, a Louisiana soul/swamp pop band comprised (mostly) of Texas musicians based in Austin, Texas.

As far as I can tell, Russell is to Shinyribs as Debbie Harry is to Blondie, which is to say Shinyribs is a band, though we might be forgiven for believing it a persona. In Texas, Russell has become a treasured and revered figure, a big guy in a loud suit injecting junk pop with soul on festival stages. A remarkable empath who never mocks his material (even when he's playing the Bee Gees' "Stayin' Alive" on uke behind the wheel of his truck), Russell has built Shinyribs from the ground up. It started out as a revenue-generating solo side project when he was in The Gourds, but after that band went on hiatus in 2013 Shinyribs became a vehicle for Russell and Gourds drummer Keith Langford.

Eventually the group grew to encompass bassist Jeff Brown, keyboardist Winfield Creek, a horn section (the Tijuana Train Wreck Horns, namely Mark Wilson on saxophone and flute and Daniel "Tiger" Anaya on trumpet) and backing singers Alice Spencer and Sally Allen (Shiny Soul Sisters). Violinist David Levin joins them on some gigs.

It's this big band that finds expression on Shinyribs' independently released fourth album I've Got Your Medicine, a rollicking little miracle produced by Jimbo Malthus (late of Squirrel Nut Zippers) that apparently chases the band's live sound. Russell wrote nine of the album's joyfully noisy 12 tracks, most of which feel like unearthed regional hits from forgotten labels like Minit-Instant, Ace, Imperial and Sansu, produced by mad alchemists like Cosimo Mattas and Dave Bartholomew.

"I Don't Give a S***," which Russell sings with Spencer, comes off as a rocked-up version of a lost George Jones and Tammy Wynette duet. "Ambulance" uses the dissonant "Devil's Interval" (the augmented fourth -- "ti-fa" -- often used in emergency sirens) to great musical effect. And "Tub Gut Stomp & Red-Eyed Soul" provides a showcase for Russell's wit as well as his John Hiatt-esque vocals.

Russell's lyrical gift is evident in the title track:

You say you feel like a ghost or a Star Castle arcade machine

There's a mall down inside you -- nah, you never bought that dream

The covers are also carefully chosen as Russell, who produced the 2015 compilation Cold and Bitter Tears: The Songs of Ted Hawkins, leans into the street bluesman's "I Gave Up All I Had." Hawkins performed the song as a spare acoustic ballad with his wife. Here it's a smoldering horn and organ-driven rave. Meanwhile Allen Toussaint's more familiar "A Certain Girl" is sexed up with a catchy call-and-response treatment, and the Toussaint McCall/Patrick Robinson ballad "Nothing Takes the Place of You" is a straight-ahead, wonderfully sung soul track.

I Got Your Medicine coheres as a record, not simply as a collection of disparate tracks. As such it's probably already as anachronistic as it sounds. But if you can't get to a Shinyribs show, it may be the next best thing.

...

After the sad news of the death of character actor Bill Paxton last week, Karen Tricot Steward at local public radio station KUAR-FM, 89.1, asked me to come in and talk about One False Move, the 1992 film that Paxton did with Billy Bob Thornton that in retrospect seems like one of the most important movies of the 1990s.

One False Move is one of the prime examples of the hard-violence films that started appearing about that time. One False Move beat Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs into theaters by a few months, and when I rewatched it last week, my intuition that it is a better film than Tarantino's breakout was confirmed. While there's a certain low-budget awkwardness that's apparent -- primarily in the early scenes -- in One False Move, it is a wonderfully acted and terrifically written (by Thornton and his friend from Malvern, Tom Epperson) movie. It feels European in its sensibility as it treats the American South as dark but ultimately scrutable territory.

It's in part a road movie that has three desperate drug hijackers, Ray (a volatile and neurotic Thornton), the cerebral sociopath Pluto (Michael Beach) and Ray's relatively innocent girlfriend Fantasia (Cynda Williams, who was married to Thornton at the time) running from the murders they committed in Los Angeles to Houston and on to Ray and Fantasia's hometown of Star City, where Dale "Hurricane" Dixon (Paxton) is the good-ol'-boy police chief.

The film cuts back and forth between the criminals' progress and Dixon's interactions with the Los Angeles detectives who fly in to intercept the killers in Star City. In this role, Paxton, who at the time may have been best known as nasty older brother Chet in the teen comedy Weird Science plays Dixon as a loudmouth version of Sheriff Andy Taylor, albeit with some of Barney Fife's lust for law enforcement glory. In six years as police chief he has never pulled his weapon, and he's eager to engage the bad guys.

But it turns out that nothing is quite so clear-cut in One False Move. It's as gritty as any Jim Thompson noir, although there's a certain humanistic quality that's absent from some of the films it anticipated -- like Tony Scott's True Romance and Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers.

...

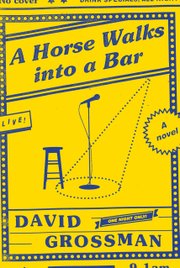

David Grossman's new novel A Horse Walks Into a Bar (Knopf) sounds gimmicky. It takes place during a monologue by a slipping-down Israeli comic named Dovaleh G (for Greenstein), who's working a half-empty club in the small city of Netanya, a place about the size of Little Rock which lies between Tel Aviv and Haifa.

Dovaleh has invited his childhood friend, a recently retired and recently widowed judge, to his performance, a request that baffles His Honor because he doesn't remember the comic. But slowly it dawns on him that the two had attended the same summer camp where he had witnessed young Dovaleh humiliated. But he still doesn't understand why he has been asked to witness this particular show.

But he goes anyway, expecting that he'll be able to slip out after a while, having discharged his obligation. But as Dovaleh starts to unspool his story, he manages to hook the judge even as he drives some members of the audience out of the basement club. (Every time someone leaves, Dovaleh marks it on an onstage chalkboard.) The judge begins to wonder about why he and the others stay: "How, in such a short time, did he manage to turn the audience, even me to some extent, into household members of his soul? And into its hostages?"

Grossman, a remarkably deft writer whose work doesn't suffer noticeably in translation (Jessica Cohen has turned his original Hebrew text into English), grants Dovaleh a standard-issue unhappy childhood, with a lumpen, violent father and a flighty, distracted mother, both of whom survived Polish concentration camps. (Joseph Mengele was like their family doctor, he jokes.) This mirrors the author's biography, and it's not hard to get a sense of the comic as a surrogate for the comic novelist, especially when those in the audience start complaining that they didn't come to the show to see someone "working out his hangups."

The truth is, few of Dovaleh's jokes are funny. They seem to serve as transactional markers, excuses for the painful story he insists on telling. To keep from being beaten up, the young Dovaleh learned to walk on his hands, an act that confounded his tormentors and insulted the dignity of his father. Now, as a full-fledged adult with a broken marriage, five kids and a prostate cancer diagnosis, he's reduced to literally beating himself up on stage, slapping his head so hard his glasses fly off and break. He taunts those who feel compelled to stay and stare at him -- "Wait, you're from the settlements? But then who's left to beat up the Arabs?" -- as he warily circles around the narrative.

There is a woman in the audience who remembers him as a kind and gentle boy, her protector. The judge remembers how Dovaleh's appearance in the summer camp provided him with some cover -- had the other boys not had Dovaleh to torture, they would have turned on him.

While at the summer camp Dovaleh was abruptly pulled out of line and told he was to be taken home to attend a funeral. But because of a bureaucratic oversight, no one told him who had died. So he begins a long ride from the camp to Jerusalem in the company of a driver who can't tell Dovaleh what he needs to know, so he tells him jokes instead.

I've read Grossman before and especially admired his somber 2008 novel To the End of the Land, which he wrote as a charm to protect his youngest son, Uri, who was serving in the Israeli military. It didn't work, for as Grossman was completing the book word came that Uri had been killed in Lebanon.

In a way, A Horse Walks Into a Bar feels like Grossman's response to the loveless universe that shames such naive magical thinking. Dovaleh is bloody and he's bowed -- but he's not hopeless. He's human underneath it all. He sweats. He bleeds. He needs a witness.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 03/12/2017