Second in a series

JONESBORO — Roseetta Robinson wept alone on Halloween 2011 after a policeman killed her father.

There were no protests, no riots, no public calls for accountability. No activists or TV cameras showed up in Jonesboro.

Her father, Cletis Williams, was black. Former Jonesboro patrolman Nick Holley is white.

Williams, 57, didn’t have a gun, and he was inside his home.

“If it were to happen now, it probably would have gotten more attention,” Robinson said, noting the added media coverage of police shootings in recent years.

Williams was one of 53 Arkansas black men killed or wounded by police in the past six years, an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette investigation found.

Seventeen of them, like Williams, were unarmed.

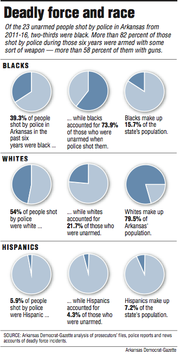

Black men accounted for 73.9 percent of the unarmed suspects shot by police in the years studied by the newspaper. They make up 7.5 percent of the state’s population.

By comparison, police shot five unarmed white men and one Hispanic man from 2011 through last year. White men make up about 37.9 percent of Arkansas’ population; they accounted for 21.7 percent of all unarmed victims shot by police.

Not every police-shooting case reviewed by the Democrat-Gazette involved a white officer shooting an unarmed black man. In a handful of cases, the officers were black.

And in most cases, regardless of the participants’ race, the person shot by police was armed.

Arkansas has not seen the level of outrage and protest that police killings of unarmed black men sparked elsewhere in recent years, but the tension between police and people of color exists here, the Democrat-Gazette’s research shows.

It’s nothing new, said state Sen. Joyce Elliott, D-Little Rock.

“Everyone is seeing it now because there are cameras everywhere,” she said.

“Black people aren’t surprised because they’ve experienced it for years. It’s taken cameras to validate what we’ve been saying” about police treatment of blacks.

Criminal justice experts caution against drawing sweeping conclusions about race and police shootings from raw statistics.

The outsize share of black men who have been shot by police is disturbing, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that it’s entirely police officers’ fault, those researchers say.

[DEADLY FORCE: Complete Democrat-Gazette series investigating police shootings in Arkansas]

Joseph Rukus, a criminology professor at Arkansas State University, said there’s a disproportionate number of blacks caught up in the criminal justice system.

“What this highlights is it’s an overall problem,” Rukus said. “It doesn’t show racial bias on police per se, but racial bias in the criminal justice system as a whole.”

Civil rights leaders agree with Rukus that blacks are systemically overrepresented, but they aren’t as quick to shift blame away from law enforcement, pointing out that police in Arkansas are far more likely to shoot an unarmed black man than an unarmed white man.

Does that mean police perceive a greater threat when dealing with black suspects?

“That’s a good ground of inquiry,” said Rukus, who conducted research in Ferguson, Mo., last summer. “We have to take it in the context of the neighborhood where it occurred. Is it cause for concern? Yes.”

BEHAVIOR IS TARGET

Law enforcement officials largely dismiss the idea that implicit bias is widespread within their ranks. Instead, they cite high crime rates in areas with predominantly black populations.

Some officers are “bad apples,” or as Little Rock Police Chief Kenton Buckner put it, there are “some that I wouldn’t want making a run to my mother’s house.”

But most cops are fundamentally good guys who want to do the right thing, he said.

Shuffling through a stack of spreadsheets scattered on his desk, Buckner, who is black, recites his department’s arrest statistics — about 70 percent of arrestees are black.

Therefore, he reasons, the majority of suspects shot by Little Rock officers would be black.

The newspaper’s findings bear that out: 78.6 percent of those killed or wounded by Little Rock officers since 2011 were black — the highest rate of any department in Arkansas when adjusted for population.

Buckner said the “socioeconomic cocktail” of single-parent homes, substance abuse, mental illness and lack of education plagues the city’s black youths.

“That’s uncomfortable for people to hear, but it’s a fact,” he said. “The truth is the truth. And in no way, shape or form would anyone be able to say to you that we are targeting African-Americans because of their race or skin color.

“We target people because of their behavior.”

POLICE CULTURE

Buckner may be right, said Cody T. Ross, a University of California-Davis researcher who has studied police shootings across the nation.

His research has flagged Pulaski County and seven other U.S. counties where “racial bias in shooting rates is strongest.”

The other counties were Miami-Dade County, Florida; Cook County, Illinois; Los Angeles County, California; Orleans Parish, Louisiana; Harris County, Texas; Baltimore County, Maryland; and Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

Police departments in those counties, including Pulaski, “may benefit from [a] review” to determine whether arrest and shooting numbers are a result of racial bias or higher criminal activity among black residents, Ross said.

Matthew DeGarmo, a criminal justice professor at ASU, said crime rates may be higher in Arkansas’ black communities because of a history of systemic racism in the state.

Black families, he said, were isolated into segregated neighborhoods. Those communities became impoverished after jobs moved away, which sowed seeds for increased criminal activity.

“In many places, officers know that African-Americans commit more crime, so when an officer sees a black suspect, that can affect their actions,” he added.

Such a notion frustrates Pulaski County Circuit Judge Wendell Griffen, who instead sees a police culture that allows “incompetent” officers on the streets.

“Why would people who profess to be trained in subduing unarmed people using less than lethal force be killing so many unarmed people and disproportionately doing so when that person is black and male?” he asked.

For example, Carleton Wallace, who was black, was killed by a barely trained officer on Sept. 8, 2012, in Alexander, records show.

Officer Nancy Cummings told detectives she accidentally shot the unarmed 30-year-old in the back while arresting him.

Cummings had worked for the Alexander Police Department for seven months, but had not attended the police academy. Her only firearms training had been target practice, according to trial testimony.

Cummings was charged with manslaughter. A jury acquitted her.

Wallace’s family has a civil suit pending against Cummings and the city of Alexander in federal court.

Allowing untrained cops to patrol the streets leads to preventable police shootings, said Griffen, who is often outspoken on civil rights issues.

“That’s a charitable conclusion,” Griffen said. “The damning conclusion is there is a culture in policing that intends to kill people — two out of three of which are black males — who aren’t a lethal threat.”

‘YOU SHOT ME’

In retrospect, the paths that led officer Nick Holley and Cletis Williams to a confrontation on Oct. 31, 2011, seem clear.

From 2010-12, Holley used excessive force 14 times when arresting suspects, four times more than the average Jonesboro cop, according to federal court records. Of all of the Jonesboro officers, Holley was the only one to resort to force more than 10 times, court records show.

Jonesboro’s population is 18 percent black. Holley patrolled in a predominantly black neighborhood of the city, and 10 of the 14 suspects he used force to arrest were black.

Williams, an Army veteran, started having problems with the law in Jonesboro in 2009 after he was ticketed for excessive noise.

On Oct. 10, 2009, an officer stopped him while he walked along the street and arrested him on a warrant for failing to appear in court on the noise citation.

After that, the warrants began to snowball, Craighead County District Court Clerk Joe Monroe said.

Police stopped Williams every few months for the next two years for infractions like riding his bicycle without a light or driving with a broken tail light.

His daughter believes those minor violations were simply excuses to stop a black man.

When Holley saw Williams riding his bike home that Halloween day in 2011, Williams was named in 16 bench warrants for failure to pay fines and seven for failure to complete public service — all misdemeanors.

He was also due in federal court the next day for a hearing in a pending lawsuit that he had filed against guards at the Craighead County jail for excessive use of force.

So when Holley knocked on Williams’ front door, Williams asked the officer to issue him a citation commanding him to appear in court, instead of arresting him.

When Williams reached out the door to show Holley some papers indicating that he had a federal court hearing in the next few days, the officer grabbed his arm.

A struggle ensued, Holley said. Williams dragged him into the mobile home, he said.

Holley said he tried to subdue Williams with a Taser. It didn’t work, and Williams ripped the device away, the officer told investigators.

Williams then jammed the Taser into Holley’s shoulder, he told detectives. They never found any burn marks from the Taser on Holley’s uniform or his skin, investigative reports say.

Holley said he fell on his back with Williams on top of him.

“That’s when he said, ‘You shot me,’” Holley said in his police interview.

The struggle continued, Holley said, and he fired several more times, striking Williams in both arms and five times in the chest.

“I was scared,” said Holley, whose actions were ruled as justified.

FADING SUNSHINE

Roseetta Robinson, 34, moved to Memphis after her father’s death.

Jonesboro didn’t feel like a place to raise black children anymore, and those drives past the empty lot where her father’s mobile home once stood never got easier, she said.

In October, four of her six children, sat across from her in a dimly lit living room in Memphis as she told the story of what happened to their grandfather five years earlier.

Hearing police sirens on Jonesboro’s Warren Street, Robinson had stepped out her front door and peered through binoculars several blocks to south.

Through the fading sunshine, she could see Jonesboro police cars lined up along the road near her father’s house.

But she didn’t think much of it and returned inside.

That’s when she noticed a TV breaking news alert that someone had been shot.

She grabbed her keys and drove down the street, more curious than concerned.

Her dad’s mobile home was surrounded by crimescene tape.

“They killed your dad,” a neighbor said.

Robinson had planned to take her kids trick-or-treating that night.

Instead, she sat sobbing on the pavement surrounded by police.

Her children learned to hate Halloween that day, she said.

‘NOT THE FIX-ALL’

After a series of high-profile shootings across the country since 2015, police departments everywhere have put more emphasis on socalled community policing.

In the past month, for example, Fayetteville police donated coats to needy children.

In Little Rock, officers talked with residents over coffee.

In Jonesboro, cops threw a block party in one of the city’s high-crime neighborhoods.

Photos from those events are scattered among the mugshots of wanted suspects on the departments’ social media pages.

Those may be great events, but they don’t fix the problem that exists between police and communities of color, said Griffen, the circuit judge.

“You don’t fix the situation by a community night out,” he said. “You don’t fix that situation with a ride-along. You don’t fix that situation by playing basketball with kids at night. You don’t fix that situation with a police chief talking about black-on-black crime.

“It’s an attempt to direct attention away from police who kill unarmed people and are treated like God, like they’re infallible.”

Some civil rights leaders have called for cities to require police to live within the city limits, or even in the neighborhoods they patrol. Little Rock and Pine Bluff rejected such measures in recent years.

Buckner and others have suggested a compromise. Instead of a residency requirement, cities could offer incentives for officers to live in the city.

“It’s not the fix-all, but it’s a start,” said Dale Charles, president of the Little Rock branch of the NAACP.

“If they were in the community, they’d see us for more than eight hours a day on patrol. We still see everything too much on the basis of race. We’ve got to interact, or that’s not going to change.”

‘HE’D BE PROUD’

After Cletis Williams’ death, his daughter says she changed as a parent, becoming more cautious.

Her boys, 14 and 13, will start driving in a few years. They’ll be on their own even more.

She worries that like many other black men, police will pull them over whether they’ve done something wrong or not.

She’s had that talk with them and what they should do if it happens.

“I just tell them to ‘Watch what you say, do what you’re supposed to and make no sudden movements,’” she said.

Elliott, the state senator, gave her son the same talk “over and over again.”

Sylvia Perkins did too. After a Little Rock officer killed her 15-year-old son in 2012, she told her other son and her grandsons to drive to her house if a cop tries to pull them over.

“That way I can watch,” she said.

Robinson still has questions about the death of her father.

Why didn’t Holley call for backup? Why did he shoot so many times? Why did her father have to die?

They’re all in her pleadings in U.S. District Court where she sued Holley and the city of Jonesboro.

U.S. District Judge Kristine Baker denied Holley qualified immunity, writing in an order that “a reasonable juror could find it unreasonable that Officer Holley pulled his gun and shot Mr. Williams.”

The lawsuit was settled shortly after for $22,155.

“Money doesn’t repay someone’s life,” Robinson said.

The settlement helped put Robinson through school. She graduated from Remington College in Memphis in September as a certified medical assistant.

As she told what happened the day her father died, Robinson calmly described how her father was shot seven times, and the sadness, panic and anger that surged through her that day.

But, as she described her father’s personality, her lip quivered and she buried her face in her arms: Strongwilled. Tough. Strict. Happy.

Across the room, her 16-year-old daughter’s cheeks shone with tears.

Robinson looked sideways at her family then raised her head.

“He’d be really proud,” she said.

Some officers are “bad apples,” or as Little Rock Police Chief Kenton Buckner put it, there are “some that I wouldn’t want making a run to my mother’s house.” But most cops are fundamentally good guys who want to do the right thing, he said.