WASHINGTON -- President Donald Trump and top Republicans, after failing to repeal former President Barack Obama's health care law, say their next focus is overhauling the U.S. tax code.

But they'll have to tackle the first major rewrite of the tax code in more than 30 years without the momentum of victory on health care and without the funds gained from spending cuts embedded in the health care bill.

The bill would have repealed nearly $1 trillion in taxes enacted under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, but it coupled the tax cuts with spending cuts for Medicaid so it wouldn't add to the budget deficit.

"Yes, this does make tax reform more difficult," House Speaker Paul Ryan said of the lost spending cuts and future efforts to cut taxes without adding to the deficit. "But it does not in any way make it impossible."

[PRESIDENT TRUMP: Timeline, appointments, executive orders + guide to actions in first 100 days]

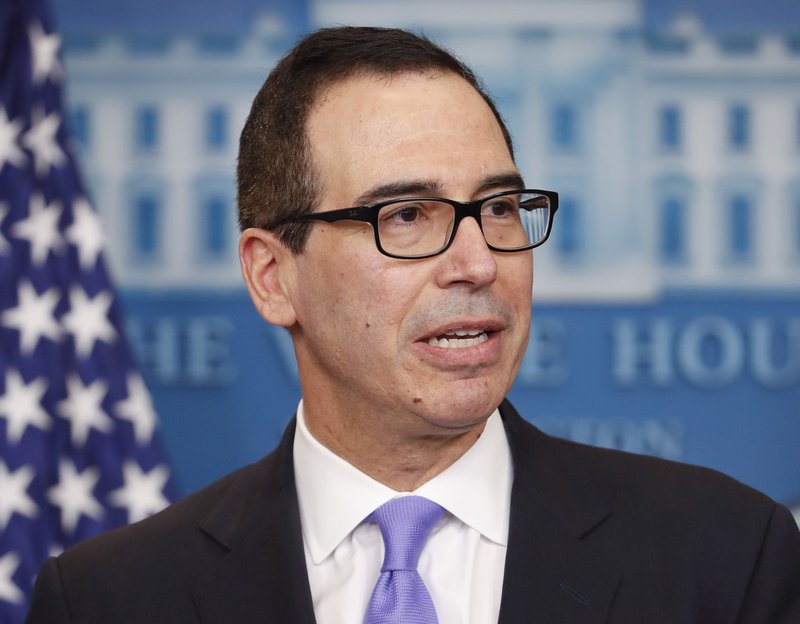

"That just means the 'Obamacare' taxes stay with 'Obamacare.' We're going to go fix the rest of the tax code," he added. Ryan said he met Friday with Trump and Treasury Secretary Stephen Mnuchin to discuss taxes.

House Republicans couldn't round up enough votes Friday to repeal and replace a law they despise, raising questions about their ability to tackle other tough issues. "Doing big things is hard," Ryan conceded.

Rep. Jodey Arrington, R-Texas, acknowledged that Friday's turn of events made him doubtful about the Republicans' ability to tackle major legislation.

"This was my first big vote and our first big initiative in the line of things to come like tax reform," said the freshman congressman. "I think this would have given us tremendous momentum, and I think this hurts that momentum."

Rep. Mike Kelly, R-Pa., said, "You always build on your last accomplishment."

Nevertheless, Mnuchin said Friday that the administration plans to turn quickly to overhauling the tax code with the goal of getting a plan approved by Congress by August. He said that if the timeline is delayed then the proposal should pass by the fall.

"Health care is a very complicated issue," Mnuchin said. "In a way, tax reform is a lot simpler."

At the White House, spokesman Sean Spicer acknowledged that the August deadline is an "ambitious one" for such a comprehensive and complicated project, but he said it's a goal the administration "is going to try to stick to."

"Tax reform is something the president is very committed to," Spicer told reporters.

The general goal for Republicans is to lower income-tax rates for individuals and corporations and make up the lost revenue by reducing exemptions, deductions and credits.

Overhauling the tax code has proved challenging to House Republicans in the past because every tax break has a constituency, and the biggest tax breaks are among the most popular.

For example, nearly 34 million families claimed the mortgage interest deduction in 2016, reducing their tax bills by $65 billion.

Also, more than 43 million families deducted their state and local income, sales and personal property taxes from their federal taxable income last year. The deduction reduced their federal tax bills by nearly $70 billion.

Trump's proposals changed over the course of his campaign -- by Election Day, his plan had moved closer to the blueprint that Ryan and other House leaders prefer. Both plans would consolidate the number of individual income-tax rates to three from the existing seven; the top rate would drop to 33 percent from the current 39.6 percent.

Trump has said he wants a "massive" tax cut for the middle class, but independent analyses of the House tax blueprint have concluded that it would benefit high-earners far more.

Mnuchin said he had been overseeing work on the Trump administration's tax bill for the past two months. He said the White House plan, which would cut individual and corporate tax rates, would be introduced soon. He did not release any other details.

The House plan retains the mortgage-interest deduction but repeals the deduction for state and local taxes. On the corporate side, the plan would repeal the 35 percent corporate income tax and replace it with a 20 percent tax on profits from selling imports and domestically produced goods and services consumed in the U.S.

Exports would be exempt from the new tax, called a border-adjustment tax.

The new tax has drawn opposition from Republicans in the Senate. Mnuchin, during an event sponsored by the media company Axios, would not reveal whether the administration will include the border-adjustment tax in the White House proposal.

Mnuchin was asked if the administration's tax plan would lower rates at all levels but not include an absolute tax cut for high-income individuals because the lower rates for high earners would be offset by increases in other areas, like reduced deductions. Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., dubbed this goal the "Mnuchin rule" during his confirmation hearing.

Mnuchin did not commit specifically on the goal but said, "The president's objective is a middle-income tax cut. ... Our primary focus in a tax cut for the middle-income [earners] and not the top."

Democrats -- none of whom supported the GOP health care bill in the House -- will be similarly wary on tax legislation, said Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer, D-N.Y. If the bill winds up benefiting high earners and not the middle-class, "it won't fly, either," he said.

Democrats aren't the only potential obstacles. As in the health care setback, the divide between moderate House Republicans and the conservative Freedom Caucus proved impossible to bridge.

"The moderates in our conference and the Freedom Caucus are truly at opposite ends of the issues," said Rep. Chris Collins, R-N.Y., a Trump ally. "And so you get one, you lose one, you get one, you lose one."

Still, Republicans, who often complained that they couldn't do a tax overhaul when Obama was president, now control the House, the Senate and the White House -- and they plan to use a Senate rule that would prevent Democrats from blocking the tax plan. But under the rule, the package cannot add to long-term budget deficits, meaning that every tax cut has to be offset by a similar tax increase or a spending cut.

Ryan made this case to fellow House Republicans in his failed effort to quickly gain support for the health plan.

"That was part of the calculation of why we had to take care of health care first," said Rep. Tom Reed, R-N.Y.

Information for this article was contributed by Stephen Ohlemacher, Kevin Freking and Martin Crutsinger of The Associated Press; and by Sahil Kapur, Lynnley Browning, Steven T. Dennis, Anna Edgerton and Saleha Mohsin of Bloomberg News.

A Section on 03/26/2017