NEW YORK -- Georgia O'Keeffe, the pioneering modernist artist, had sensibility to spare. She lavished it on her work, but she applied nearly as much to self-presentation: the clothes she wore, the places she lived and the furnishings and objects they contained. All these elements formed a single powerful aesthetic -- in an era long before widespread branding, social media and Instagram marketing -- that was foundational to her fame and her myth.

That point is driven home by a refreshing exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum that for the first time combines O'Keeffe's art and her wardrobe with photographic portraits. "Georgia O'Keeffe: Living Modern" (through July 23) reveals how this painter of simplified images of enlarged flowers, Lake George tree trunks and New Mexico's terra-cotta hills applied her meticulous sense of austerity and detail to her every garment. Some she designed and sewed, others she had custom made and some others she bought off the rack or in antique shops.

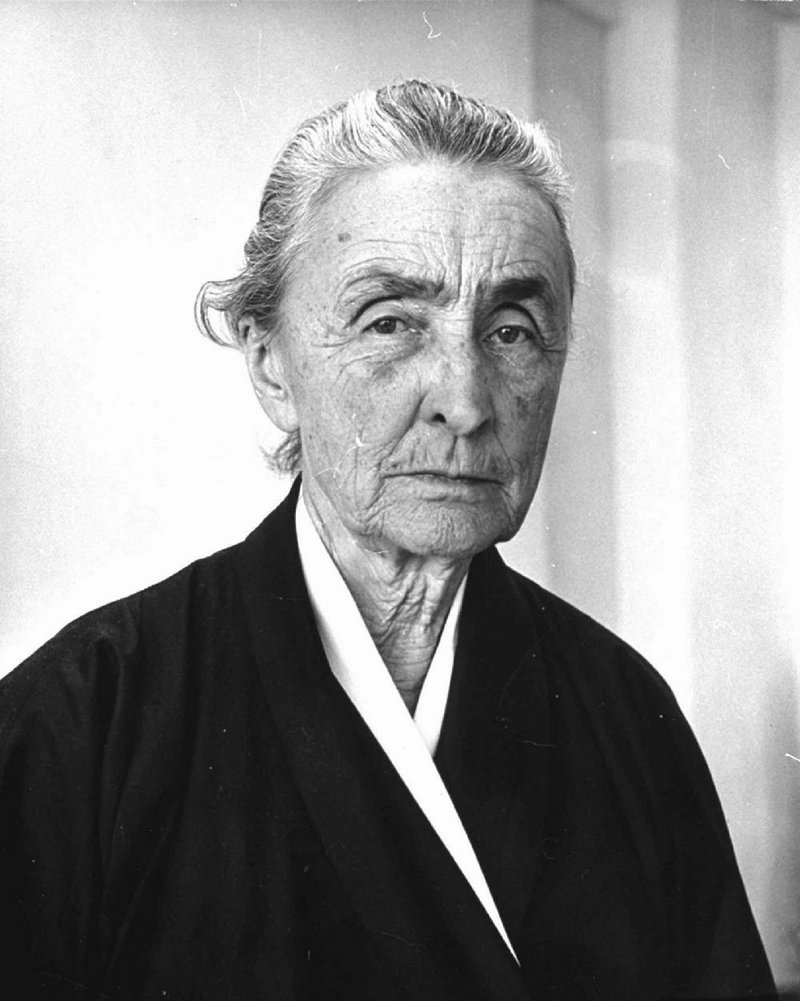

The exhibition suggests that O'Keeffe (1887-1986) wanted every aspect of her life and person, like her art, to announce her difference. She also controlled the way she was photographed as carefully as a Hollywood studio, creating a seamless merging of nature-based art and a monkish persona. The sparsely furnished structures and the landscapes she inhabited outside Santa Fe, where she spent most of her time after 1929, framed the presentation. The house near Abiquiu, N.M., that she saved from ruin and her stunningly situated Ghost Ranch, 16 miles away, figure in some of her best-known paintings and as photographic backdrops.

"Living Modern" has been organized by the influential historian of early American modernism, Wanda M. Corn, whose depth of research is reflected in an exceptional catalog. She sums up O'Keeffe sartorially as "a confident seamstress, a steady manager of her wardrobe and a well-informed shopper."

The exhibition argues that as she became modern art's first celebrity artist, O'Keeffe's self-created image shaped her work's accessibility, while at the same time shielding her privacy. This unity is revealed in the links drawn among some 50 works of art and 50 garments or ensembles, accessories included, and nearly 100 photographs taken by 23 photographers, from Ansel Adams to Andy Warhol. The greatest number of these images were taken by O'Keeffe's husband, the eminent photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz.

For years, O'Keeffe limited her wardrobe to mainly black and/or white, until the Southwest loosened her color sense a bit and introduced her to denim and jeans. She favored an androgynous look, frequenting the same New York men's tailor -- Knize -- as Marlene Dietrich, liked Ferragamo flats and wore little jewelry. A rare favorite, visible in many photographs, was a brass brooch made for her by Alexander Calder. It represents her initials, OK, with ancient rock-painting complexity, and she wore it vertically to make it more abstract.

In the final gallery hangs a photograph of O'Keeffe wearing a Knize black tailored suit with a white shirt and four-square. She looks ancient and wise, a bit like Marcel Duchamp, a bit like Fred Astaire. Dan Budnik took the picture in 1975, but didn't print it until 2000. O'Keeffe didn't need further proof of her self-creation, but it's sad to think she never saw it.

"Georgia O'Keeffe: Living Modern," through July 23, the Brooklyn Museum. Info: brooklynmuseum.org.

Travel on 03/26/2017