Television is like most of the technologies humans have developed. It has remarkable potential, but we mainly put it to banal purposes. We use it as a narcotic, a way to mindlessly pass time. It's a voice in the other room, a nightlight.

There are plenty of voices that would defend this practice, arguing that we deserve our circuses, or that the last thing we need is to be challenged by a TV show. Fair enough. People have enough to worry about without confronting the epistemological limits of the human mind in Sunday prime time.

I don't watch enough television to argue that HBO's The Leftovers is the best show on the air. I don't know that anyone does, even the professional TV watchers who write recaps of high-profile series for blogs and online editions of newspapers.

(Noel Murray of Conway writes The Leftovers recaps for The New York Times. I highly recommend them. Murray and his wife, University of Central Arkansas professor Donna Bowman -- who used to write the Breaking Bad recaps for the Onion A.V. Club -- are two of the best critics working the surprisingly rich series recap vein. Just sayin'.)

I hear about things every day that I know I'll never get around to checking out. (American Gods. Orphan Black. Sneaky Pete. I tried Taboo.)

But I am watching The Leftovers and am consistently surprised by how the show, a black comedy about the world after a Rapture-like event, interrogates our received notions of family and religion, sin and redemption and the underlying mystery of human existence. The Leftovers is ambitious; unafraid to take on the biggest questions. But what's remarkable is that it's able to combine intellectual seriousness with a playfulness uncommon not only in TV or movies but in any work of art.

I have no idea how many people watch it, but probably a fairly small number. But like everything else in this digital age, it will be archived and accessible to anyone who cares enough to seek it out. (It's not too late if you want to catch The Wire; and you can watch most of Sid Caesar's Your Show of Shows on YouTube. If you want to relive your childhood, you can load up on DVDs or squat on one of the nostalgia channels.)

It used to be that television was a binding agent that held our big country together. In the old days, when most people had access to only two or three broadcast channels, figures like Ed Sullivan, Jackie Gleason and Walter Cronkite held sway over millions of imaginations. They and their programs served as cultural tent poles, covering even the Bohemian Americans who defined themselves in opposition to pop culture. In the 1960s it was possible to live without TV -- it might have seemed noble to live without TV -- but it was impossible to be ignorant of the prevailing stars and shows and remain engaged with fellow citizens.

Now, television is balkanized and -- while networks and sponsors still aspire to reach millions -- broadcasting is a quaint fantasy. Where once TV was widely viewed as a vast wasteland, now it's rich and varied, a lush jungle teeming with freaks and monsters, philosophers and saints. While there's likely as much bad TV now as there ever was (probably more) there has never been as much "quality" programming available to watch. Your options have never been better.

But I'm starting to think The Leftovers, now in its third and final season, is something better than just must-see TV.

It challenges the notion that collaborative art made for mass consumption can only be so good -- that the inevitable concessions that must be made to potential commercial prospects keep any television product from achieving the sort of artistic transcendence of highly individualist works such as novels or paintings. Committees don't produce masterpieces in part because collaboration -- even with other serious-minded artists -- is itself a compromise. When you have to please decision-makers primarily concerned with attracting and holding the attention of a certain number of viewers in order to get your work on the air, there's going to be pressure to make the work more user-friendly.

This is a little different when you're dealing with a subscription service like HBO, which doesn't rely on advertisers but on people who've essentially bought a ticket to watch the programs they produce. As long as HBO offers immensely popular content like Game of Thrones (they're developing four spin-off series) they can afford to keep developing "prestige" shows like The Leftovers. (It's not entirely analogous to Columbia Records keeping the relatively low-selling Bob Dylan on their label through the '60s, but it's close.)

But even the relative freedom afforded by a pay cable channel would seem to have limits. The Leftovers is shutting down after three seasons presumably because its creators, Tom Perotta (who wrote the novel on which the first season was based) and Damon Lindelof (co-creator and showrunner of Lost), will have told the story they meant to tell.

Which isn't the story of how the world's human population was decimated by an event -- the Sudden Departure -- that somehow evaporated millions from the planet, but a story about the ways the survivors sought to cope in the aftermath.

Because it seemed that the disappeared had been harvested at random rather than selected for any quality of conscience or soul, established religions were destabilized and cults sprouted. Some were led by charismatic figures acting out of renewed conviction or opportunism, while others were committed to reminding people of the apparent meaninglessness of their existence.

The first season was concerned largely with Kevin Garvey, the police chief of a small town in upstate New York (Justin Theroux), whose wife Laurie (Amy Brenneman) left him to join the Guilty Remnant, a nihilistic cult given to yippie-like disruption that arbitrarily requires its members to maintain a vow of silence, dress in white clothing and chain-smoke. Laurie left Kevin with their teenage daughter. Meanwhile, her slightly older son -- whom Kevin adopted -- was in thrall of a (charlatan) faith healer.

Over the course of the first season, Kevin became romantically involved with Nora Durst (Carrie Coon), who lost her husband, son, and daughter in the Sudden Departure. Nora's brother Matt (Christopher Eccleston) is a Christian minister determined to debunk the idea that the Sudden Departure was the Rapture by publishing a newsletter proving that the departed were not especially virtuous. His truth-telling made him remarkably unpopular.

In the second season, most of the cast moved to the fictional town of Jarden, Texas -- the largest community in the world from which no one disappeared during the Sudden Departure -- and therefore a place of pilgrimage. Another unexplained event occurs, the Guilty Remnant shows up and Kevin takes an audacious trip through the afterlife that includes a purgatorial stay in a bland luxury hotel. While the first season hewed relatively closely to the plot of Perrota's novel, the second season was a trip that left the audience unsure of whether the events depicted were happening in the show's reality or in the unreliable protagonist's fever dream. For a show about loss and grief, it got pretty kooky.

Now, in the third season, it's apparent some of the people around Kevin noticed his death and resurrection. Some are positing him as a possible savior of mankind. And it's starting to look like he's trying the idea on. Four episodes into the final season (episode five airs tonight), it's impossible to guess where this story is going. For those of us who've watched a lot of movies and have become acclimated to the rhythms of long-form episodic television, that's a really rare thing.

...

Elizabeth Shores' byline might be familiar to Arkansas readers. She went to work at the Arkansas Democrat in 1979 and was a newspaper warrior through most of the next decade. Full disclosure requires me to say I edited some of her investigative work for the alternative newspaper Spectrum Weekly in the late '80s and early '90s. After a while she found work in academia and a few years ago the University of Georgia Press published her biography of botanist Roland McMillan Harper.

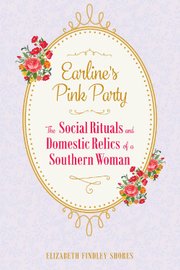

Now she's back with a remarkable and inventive work called Earline's Pink Party: The Social Rituals and Domestic Relics of a Southern Woman (University of Alabama Press, $29.95). It is essentially a biography of her grandmother, Earline Moore Finley of Tuscaloosa, Ala., who was born in 1896 and died in 1953, five years before the author was born.

Earline was a schoolteacher who married "a man with a modestly aristocratic lineage" who raised her children in a three-bedroom bungalow on a respectable Tuscaloosa street and could afford domestic help. She was not wealthy, but had plenty of leisure time, which she mainly used to pursue the domestic arts of cooking and sewing.

By examining her grandmother's heirlooms and digging into family and social history, Shores has produced a fascinating and insightful look into the ordinary life of a certain kind of white Southern woman that also examines the casual and obligatory racism of the times. Piecing together scraps -- brief handwritten notes, recipes scribbled on the backs of envelopes, short letters to a daughter -- Shores has managed to create a surprisingly detailed portrait of a woman of her times, in a way as stunted and oppressed by the moral directive to "be nice" and by her community's obsessive fear of black ascendancy. Shores manages to incite compassion for a woman who, she writes, "was literally incapable of empathy."

"One must be the beneficiary of empathy in order to learn its practice," Shores writes, "and she evidently did not find love or security in her relationships with her parents .... The frightening exterior world of Choctaw County, where hundreds of economically oppressed freedpeople surrounded Earline's home and family, constantly reinforced the idea ... that the world is a dangerous, even malevolent place."

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 05/14/2017