There was a moment in the late 1970s when we went to discos.

We went there to dance and to meet girls. We wore what we would all now agree were stupid clothes. A friend favored terry-cloth polo shirts and Angel Flights pants. (All of the clubs we went to had a strict "no jeans" policy which apparently didn't extend to denim pimp caps.) We all looked ridiculous.

But in our defense, none of us ever thought much about disco as a musical genre. We didn't detest it the way some reactionaries did, but it wasn't something we listened to a lot either, and at least a couple of us considered ourselves musically sophisticated. One of the guys I used to go to discos with fronted a heavy metal band. I wrote songs and played guitar and spun deep blues and folk cuts on two different college radio stations. (I never attended Centenary College in Shreveport but somehow I ended up with a weekend shift on KSCL, its student-run Bic lighter with a signal that, on a good night, might have covered a few square blocks beyond the campus.)

Yet we went to discos, like everybody else. Because of Saturday Night Fever.

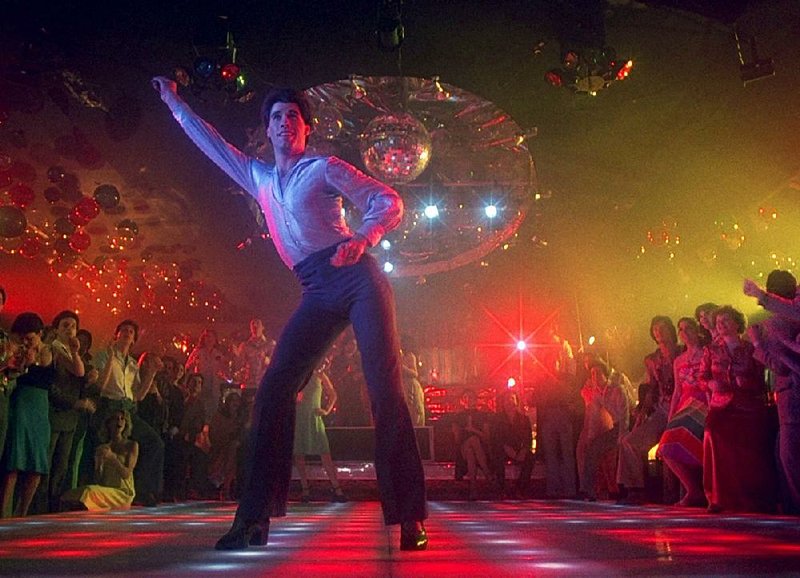

One of the things movies do, one of the reasons they're so insidiously influential, is that they provide young people -- and young men in particular -- concrete models of behavior. Movies teach us how to smoke, how to flirt, how to comb our hair and how to hold our cigarettes and pistols. They present us with characters we can ape, some of whom we can even relate to. Maybe we couldn't be James Bond, with his Aston-Martin and his license to kill, but we could all imagine ourselves as Tony Manero, paint store clerk by day, disco king by night.

They sent me a DVD of the movie recently, because it's celebrating its 40th anniversary. It was initially released in December 1977 in an R-rated version that's much better than the PG one released a couple of years later to take advantage of its record-breaking soundtrack album. It wasn't widely reviewed until February 1978, which was probably around the time I saw it. This means I saw it after I returned from an adventure in Brazil where I'd spent more than a couple nights in a huge club in Rio called New York City Disco. So I knew at least a little of dance floor culture before the movie; my friends and I were going to the Admiral Benbow Inn (which had one of Shreveport-Bossier's largest dance floors) and Daddy's Money and all the other clubs that played disco before we saw the film.

But there was something galvanizing about seeing a rough approximation of ourselves up on the screen. At the time we thought John Travolta's Tony and his Brooklyn buddies were cool; it's only through the long lens of adult reappraisal that they become pathetic. And it's only recently that I've come to regard John Badham's film as a genuinely great movie as opposed to a youthful enthusiasm. Just as I would later come to appreciate some of the disco music that, in the moment, I'd accepted as a functional background noise that provided us an excuse for mingling with young women.

A lot of people know the inspiration for the movie was a 1976 New York magazine article by British writer Nik Cohn called "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night." More than 20 years ago, Cohn admitted that he made the story up.

"My story was a fraud," Cohn wrote in London's Guardian in 1994. "I'd only recently arrived in New York. Far from being steeped in Brooklyn street life, I hardly knew the place. As for Vincent, my story's hero, he was largely inspired by a Shepherd's Bush mod whom I'd known in the Sixties, a one-time king of Goldhawk Road."

There was a real Tony Manero, who New York Times writer Charle LeDuff described in a 1996 story as "a scrawny guy who kept mostly to himself in the corners of club Space Odyssey 2001, nothing like the macho dance floor Casanova played by ... [Oscar-nominated] Travolta .... The real Tony Manero drank tequila sunrises, not 7-and-7s as the movie character did. Everybody drank tequila sunrises."

Cohn's original story was considered a fine work of social anthropology back in the day, and despite his fabricating the main character, maybe it was. In any case, it inspired a movie that was ultimately responsible for a lot of Tony Maneros. It sold a lot of white suits. It caused life to imitate it.

Saturday Night Fever is about the precarious crossing from adolescence to adulthood. The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge that separates Tony's Bay Ridge neighborhood from more genteel Staten Island is the film's key metaphor -- Tony wants to make it across, to escape his unemployed father and ultra-Catholic mother and a future working in the paint store. (When his boss points out that his co-workers have been with the shop for 20 years, Tony winces in disgust.)

Maybe the most interesting character in the film is Tony's older brother, Frank, a disillusioned priest played by Martin Shakar. Frank is quitting the priesthood, a vocation he believes he was forced into by his parents: "Tony, the only way you're gonna survive is to do what you think is right, not what they keep trying to jam you with," he tells his younger brother.

Tony seems more dissatisfied with his life in the neighborhood than his posse of close friends -- Joey, Double J, Gus and Bobby C. -- who accompany him on his weekend sorties to the Odyssey. (The real club, at 802 64th St. in Brooklyn's Sunset Park was used for the exterior shots. The club went through several incarnations as a gay bar, a rock 'n' roll club and finally a disco again before being demolished in 2005.) Annette, a neighbor girl (played by Donna Pescow, who gained 40 pounds for the role) is Tony's regular dance partner and sort of the group's mascot. She harbors unrequited feelings for Tony, who throws her over as soon as he identifies a potentially better partner.

This new partner is Stephanie (Karen Lynn Gorney), a Brooklyn girl with ambitions of moving to Manhattan, where she works as a secretary for a music publicist. She agrees to become Tony's dance partner because she sees his talent, but she's cool to his advances and wants to keep things professional. She allows Tony to help her move to Manhattan but is wary of him; he's a boy from the old neighborhood who could foil her escape.

It's significant that the ultimate dance contest, the one where (spoiler alert) Tony and Stephanie win but Tony gives the trophy to a Puerto Rican couple because he realizes they were denied first place because of racism, is located across the bridge in Manhattan. It's also not an accident that the suicidal, misogynistic Bobby C. -- torn by guilt over not wanting to marry his pregnant Catholic girl and hurt by Tony's indifference to him -- falls to his death off the Verrazano-Narrows.

What's most remarkable about SNF is its ending, which is almost what you'd expect. After a long night of the soul riding the subway, Tony turns up at Stephanie's new apartment. He tells her he's planning to move into Manhattan as well. But they don't fall into each others' arms. Instead they briefly touch hands, and Stephanie asks him, mocking his macho bravado if "he can be friends with a girl?"

And Tony, in this moment almost literally a new man, gives a grown-up answer: "I don't know," he sighs. "I really don't know."

And the movie ends, with Stephanie and Tony in Manhattan, across the bridge and separated from his dysfunctional family, Annette and his surviving childhood buddies.

It's a beautiful and moral movie, a lot more than what I took it for back when we used to go to discos.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

www.blooddirtangels.com

MovieStyle on 05/26/2017