PARAGOULD -- Kelsey Cox placed the cigarette between her lips, drew in a deep breath, letting it soothe her as it always did, and blew the smoke into a cloud, her mother said.

Kelsey, 24, started smoking when she turned 18 as a way to calm down when she was having "an episode."

Around the time Kelsey hit puberty, she started exhibiting strange behaviors that worried her family. An obsessive need to find and collect eyeglasses. Shaving her head. Eating things that weren't food -- magnets, the bristles from her hairbrush, pills by the handful, hand sanitizer.

She was hospitalized more than 100 times, and when she stood, smoking that cigarette in the parking lot next to her therapist's office on Aug. 14, she was waiting to begin yet another inpatient stay.

The plan had been in place for a couple of days -- an ambulance would take Kelsey to Rivendell, a facility just outside Little Rock. She would stay there for two weeks and then go home, stable and ready to go back to her little apartment in her parents' backyard, to her tabby cat, her golden retriever.

When the time came to start the drive, Kelsey kissed her new phone goodbye, hugged her mother and got in the ambulance.

Details of what happened on that ambulance ride are unclear, but one thing is certain -- Kelsey, in a fit of mania, while the ambulance was charging at more than 70 mph down the interstate, flung open the doors.

And jumped.

After the leap onto the concrete that had become a gray blur beneath her, Kelsey rolled about 207 feet and died nearly an hour later, according to her family. The ambulance was about 45 miles north of Searcy at the time, less than an hour from Kelsey's home.

By accounts of those closest to her, Kelsey did not intend to die that day; the practical results of what would happen when she jumped from the ambulance just didn't compute in her brain.

'JUST LIKE ANY OTHER CHILD'

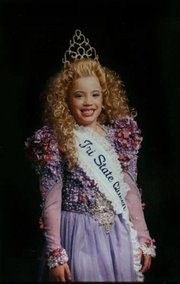

Mental illness was not evident in Kelsey until she was in the seventh grade, her family says. She competed in pageants as a child, curling her mane of blond hair and donning a beaded purple dress to walk down the runway. It helped her come out of her shell, and she even won a few of the competitions.

Kelsey and her younger sister, Lauren Waldon, participated in the pageants together. Lauren Waldon would go on to become Miss Arkansas International 2016.

Kelsey was on the autism spectrum, although this mainly meant that she would rock back and forth when she got upset.

Her mother, Jenny Waldon, thinks Kelsey could have become an artist. Ever since she was a child, Kelsey loved making art. It began with drawings and paintings, mostly of animals, and developed into sculptures of medical equipment as she got older.

"People forget that mentally ill people were children and babies, and had personalities and loved life," Jenny said. "She was just like any other child."

Things didn't get bad until a family trip to Disney World when Kelsey was 12. She had to stay behind in a psychiatric unit while her family went on the trip.

When Kelsey had episodes, she couldn't be left alone for a moment. She once squeezed an entire container of deodorant into her mouth when her mother's back was turned, while she was ordering lunch for the two of them in the hospital.

"She battled -- it seemed like once adolescence hit, between age 12 and 14 -- this other part of Kelsey's brain would emerge, and she couldn't control it," said Jenny. "She would ask, 'Why can't I be normal? Why did God make me this way? Why can't I be like other people in the family?'"

Kelsey started attending special classes where she didn't have to move around in the school hallways. She wasn't in school enough to make it into the yearbook, so her mother made her a book that chronicles her school years.

'SCARED OF DYING'

On July 27, Kelsey started on another downward spiral. She overdosed on pills, had to be taken to a hospital emergency room and was admitted.

Kelsey's overdoses were never suicide attempts, Jenny said.

Kelsey ate pills as if they were Tic-Tacs because she liked the weight of them in her hand, liked to feel them rolling over her tongue. But once they hit her stomach, she always ran to her mother, crying that she didn't want to die.

"Every time that she would take something, for the most part, especially the times she would take pills, she would come tell you immediately because she was scared of dying," said Sue Waldon, Kelsey's grandmother.

After the July incident, Kelsey was scheduled to go to Missouri for an inpatient stay at a mental-health facility there.

Leaving the hospital, Jenny went home to pick up clothes for her daughter, but on her way, she got a call from her father-in-law, who had stayed with Kelsey at the hospital.

Jenny needed to return and pick up her daughter, he said. Kelsey had pulled out the IVs in her arm and left the hospital.

Jenny whipped the car around and headed back to Arkansas Methodist Medical Center in Paragould.

A Paragould police report says that after she left the hospital, Kelsey wandered behind a Dodge's convenience store.

When police found Kelsey, Jenny asked them to take her daughter to inpatient care; Jenny was worried she wouldn't be able to prevent Kelsey from hurting herself.

Officers told Jenny they couldn't take Kelsey anywhere without an official pickup order, and they advised her to just take her daughter home.

Jenny loaded a frantic Kelsey into the car. The trip to Missouri was canceled -- they had no way of transporting her to the center while she was in an agitated state.

On the way home, Kelsey tried to jump out of her mother's car, yanking on the handle of the passenger door. Jenny veered across traffic to the side of the road and grabbed her daughter.

"Kelsey, what do you think is going to happen if you were to just get out of that car and take off? What do you think would happen going 40 miles per hour?" she asked.

"I would just get up and go and hide, and y'all aren't going to find me because I'm not going back," Kelsey replied.

This conversation has Jenny convinced that when Kelsey leapt from the ambulance, her mind wasn't on death. Jenny says her daughter thought she could get out of the car, no matter how fast it was traveling, and bounce back, ready to run.

Mother and daughter sat on the side of the road until Kelsey's stepfather arrived to help take Kelsey home.

A DAUNTING TASK

After they went home, Kelsey's therapist arrived at the house. Kelsey was yelling and crying. Her speech was starting to deteriorate into half-sentences and unintelligible mumbles, according to police reports dated July 27.

Police tried to calm Kelsey. She told them that she needed to go to the bathroom. After a few minutes, she called for her therapist to enter and said she had done "something special," according to reports.

Kelsey had cut her arms and legs with a disposable razor and had to go back to the emergency room for treatment. She was transported to Rivendell later that day.

She got out of what would be her last stay at a mental hospital Aug. 6. She went to stay with her father, Frankie Cox. The two spent the next few days going to flea markets looking for eyeglasses to add to Kelsey's collection, Frankie said.

When Kelsey went back to her mother's house, she had a few good days, but then she used rubbing alcohol as an enema and had to go back to the emergency room.

Her parents took precautions to protect Kelsey from herself -- a lock box for all the pills, locks on every door -- but it was a daunting task.

"I can't tell you how many times I've been in an emergency room and just slid down the wall from complete exhaustion and devastation because I couldn't help her," Jenny said.

'GET SOMETHING DONE'

Jenny has now immersed herself in advocacy work to get more long-term mental health facilities for adults in Arkansas -- doing everything she can think of, from talking to reporters to meeting with legislators.

"Once they appear stable, they have to let them go," Jenny said of most mental health centers. "It's temporary; it's not a long-term thing."

Most long-term mental health facilities in Arkansas are for children and adolescents. The Arkansas State Hospital is one option for inpatient stays of more than 30 days.

Frankie Cox said that when Kelsey switched medications, she was never in a facility long enough for employees to see if the new drugs really worked.

Jenny filed a lawsuit Thursday alleging that the ambulance technicians are at fault for her daughter's death.

The seven-page lawsuit, filed by Memphis-based attorney Mark Geller, alleges that Wendell Jones and Gary Goff, who work for Arkansas Excellent Transport Inc., a Walnut Ridge ambulance service, were negligent in their care of Kelsey on the trip.

The ambulance technicians listed in the lawsuit made "disparaging and inflammatory comments" to Kelsey about her willingness to be employed, according to the suit.

Other claims outlined in the suit state that Jones and Goff failed to properly treat Kelsey, that they failed to properly restrain her and that the company failed to properly train personnel.

The lawsuit demands a jury trial in White County.

Jones said he had no comment and that he had not yet seen the lawsuit.

Kelsey's family continues working to mend. Frankie Cox said he has good and bad days and is trying to return to work. He has lost 15 pounds since Kelsey's death.

Lauren Waldon said that, to her, Kelsey's death still doesn't feel real -- her sister was absent so often that it feels like she's on an extended stay at a mental hospital.

In the days after Kelsey died, just the sound of an ambulance's sirens made Jenny cry, Sue Waldon said.

"Kelsey's story is not over because I know Jen will take it as far as she needs to go to get something done," Sue Waldon said.

SundayMonday on 11/19/2017