Judy Joyner thought when she reached her golden years, she would be on a beach somewhere, soaking up the sun with her husband by her side.

Instead, she sleeps just a few feet away from her dining room table; handmade schedules decorate her walls. They show when the kids -- ages 14, 13, 10 and 7 -- take their baths, get up and catch their respective buses.

"I am what I refer to as a guardian grandparent," Joyner, 66, wrote in a letter to an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reporter. "A traditional grandparent loves, pampers, spoils and returns the grandchild to their parents. That is hardly my duties."

She started caring for her daughter's children about a decade ago after the state took custody of them.

At first, money was tight and feeding growing grandchildren proved difficult.

Her husband left when she took guardianship of the kids; the two had worked all their lives planning to travel when they retired, but now they are divorced and he is doing that traveling without her.

"He was my best friend, and he was at the age where he wanted to travel and he wanted to do things that he had worked hard for all his life," Joyner said in her Pine Bluff home. "He just didn't want to be strapped with children, and I can understand, but it threw me because it was a sudden thing."

She still keeps a snapshot of the two of them in her room. In the picture, she is wearing a black dress and lipstick, but said she doesn't have time to care about dressing up now. Her clothes come from Goodwill, and for a while after he left, the kids' clothes came from the second-hand store, too.

She had very little savings of her own.

So, Joyner needed some help getting started. She turned to Targeting Our People's Priorities With Service, TOPPS, a Pine Bluff nonprofit that serves kids and families in need.

TOPPS provides meals for children and sends home boxes of food to families that need it. Joyner said she needed the help after her husband left because she was rebuilding her life entirely, down to buying new dishes.

She got books, food and support from TOPPS; she needed the books to home-school one of the children who hadn't yet learned to read and needed the support because the children came to her with emotional problems. She is still trying to get some of them to stop sleeping with the lights on.

Joyner has since stopped relying on food from TOPPS, although the kids still go for the mentoring and tutoring programs -- Joyner's main concern now is the emotional and spiritual well-being of her grandchildren.

She has three degrees and one year of law school under her belt. She worked two jobs before she retired -- one on the legal team for a railroad and the other as a teacher in Memphis, which has worked to her advantage monetarily.

She's lucky.

ONE IN FIVE

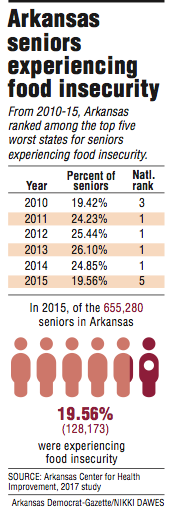

Nearly one in five Arkansas senior citizens experiences food insecurity, and many of them are worse off than Joyner. The fixed incomes from the jobs they worked don't provide enough to pay for medical expenses, bills and their food, according to a study from the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement.

The numbers grow worse for senior citizens who, like Joyner, are caring for their grandchildren, a growing population in the face of increasing rates of incarceration and drug addiction crises that have risen to epidemic levels, according to studies from the U.S. Census Bureau.

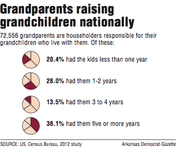

Nationally, about 10 percent of all children live with a grandparent, and the percentage of children living in a grandparent-maintained household has nearly doubled since 1970, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

In Arkansas, just over 11 percent of children live in a household maintained by a grandparent or other non-parent relative. Just over 38,155 grandparents are raising their grandchildren, and about 25 percent of those are living in poverty, according to a report from Grandfamilies, a national organization that is a legal resource for grandparents raising grandchildren.

"Particularly in the state of Arkansas, now a lot more grandparents have custody of their grandchildren and that's where their food is going," said Luke Mattingly, president of Central Arkansas CareLink, which provides resources to senior citizens. "They're sacrificing their food to feed their grandchildren, and that's really a new issue."

Annette Dove, founder and director of TOPPS, said she started noticing the problem because the kids in her program were trying to take food home, even digging half-eaten sandwiches out of the trash to present to caregivers.

"A lot of our kids are living with grandparents," Dove said. "Those grandparents are living on fixed incomes."

Fixed incomes often leave senior citizens turning to Arkansas' Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, which representatives from the Arkansas Food Bank say average from about $12 to $16 per month.

Jayne Ann Kita, a program officer with the food bank, said that because of the minimal amount of groceries that can generally be bought with SNAP dollars, many senior citizens don't bother applying. The Arkansas Food Bank organizes workshops to encourage them to apply and show them what foods they can cook on $12 a month.

One recipe was for a soup, a dish many pantries work to teach senior citizens how to make because it's cheap, easy and nutritious.

Studies indicate that senior citizens will water down their food to make it stretch through a month when they have to choose between paying for medication or paying for food.

"We understand that medication is so expensive that they're choosing between medication and food, so I think some of that awareness is growing," Kita said. "I think for a while we didn't think about it. They're in their apartment or in the house and we don't see them."

Another common tactic to save money is just to buy the cheapest food available, even if it means buying unhealthful food, which can compound health problems. Mattingly said this is particularly an issue in rural areas where the nearest grocery store can be miles away.

Donations for nutritious foods are always an issue for pantries, organizers said. The best food for senior citizens is usually low-sodium, fresh vegetables or pop-top cans that are easy to open.

. . .

Food insecurity in the senior population can also be caused by poverty or simply the inability to get up and get food, Mattingly said.

CareLink provides Meals on Wheels, a home food delivery service for senior citizens. Mattingly said many of the people served through that program have plenty of money, they just aren't physically able to prepare a meal.

This is the case for Rosemary Meritt, 82. She has had meals delivered for about a year because standing up for too long wears her out.

"Well it's just so hard for me to get around, and you know somebody suggested it one time and I thought 'Well I probably don't even qualify because I didn't know what you had to do to qualify,' " she said.

She uses a cane to walk around her house and when she gets up to feed her dog, Millie, but hauling the walker out to go to shopping is a hassle.

"I can't get out as much, and it's real hard to go to the grocery store and walk around and get out," she said.

Meritt donates to Meals on Wheels once a month, slipping $25 into an envelope. She said she can afford to pay for food, although others, like her 100-year-old aunt, can't.

"I don't know whether you're supposed to or not, but anyway I do because I can afford to send a little contribution, " she said.

Meals on Wheels has instituted a waiting list for the first time in more than a decade, Mattingly said. Funds are drying up. People are living longer. There isn't enough food to go around.

"With all of the things we need ... demand is just outpacing the funding," Mattingly said.

The waiting list is up to 50 people and Mattingly said he doesn't anticipate it disappearing anytime soon. More people will get meals as current recipients move into nursing homes or die.

Tina Hillman, a Carlisle resident who runs a food pantry for senior citizens called the Daily Bread Senior Food Pantry, said her group has senior citizens who have trouble standing in line at the pantry to get food.

In Carlisle, a town with a population of just over 2,000, eight miles from the nearest Wal-Mart, senior citizens begin lining up at the food pantry, which is housed in a Methodist church, an hour or two before it opens.

One woman took an insulin shot in the summer heat and because she had not had any food yet that day, passed out and broke her wrist.

In response, the pantry brought in students from Carlisle High School to help load cars. The arrangement helped them get their volunteer hours, required to be a part of the honors society, and senior citizens didn't have to carry bags and freezer totes out in the heat.

However, after the students started coming to help, Hillman noticed the number of senior citizens coming to the pantry jumped by about 10, a significant number at a pantry that usually serves about 50.

Students who lived with their grandparents were telling them about the food, and more hungry senior citizens were making their way to the pantry, Hillman said.

Hillman said the issue is easily and often overlooked because many senior citizens are ashamed to ask for help. Three senior citizens interviewed for this story later asked that their stories not be printed because they were not willing to speak publicly about needing assistance.

"The face of senior hunger is not lazy," Hillman said. "It's not the typical stereotype. It's people that have worked all their life, have raised their kids."

Joyner said raising her grandchildren has made her a different person who is more willing to ask for help.

She's less proud, more spiritual, tougher. She said she couldn't have done it without assistance from TOPPS, state child care services and the foster care system, which kept the kids for two years before she was able to take guardianship.

After her husband left, Joyner said, she signed the divorce papers and walked out of the lawyer's office in a daze, leaving her purse behind. She barely remembers the year that followed.

"He left me, and for a year it was just dark. Dark, dark, dark," she said.

But she had a dream about one of her grandsons contacting her while she lounged on the beach, and he was asking her to come to his execution. In the dream he told her that he had killed four people and wanted his Granny there for his dying moments.

She then dreamed nearly the opposite -- she was being wheeled from the nursing home after having cared for the child through his graduation from divinity school, and knew she had made the right decision.

"There's a lot of grandmothers doing what I do. And grandfathers too," Joyner said. "They're saying, 'I'm not going to have a generational curse on my family.' That's what we're fighting for. To save our family."

Style on 11/19/2017