HARARE, Zimbabwe -- For the first time in decades, in a country where protests have often been violently dispersed, thousands of Zimbabweans marched through the streets of the capital demanding the resignation of their president, a swelling of public opposition that followed a military takeover last week.

Thirty-seven years after he came to power, Robert Mugabe's rule is now under threat from multiple fronts. First, on Tuesday, there was the late-night military operation that placed him under house arrest. Then, on Friday, his party voted for him to be recalled. And Saturday, a diverse mix of opposition groups marched through the city in what appeared to be the country's largest-ever demonstration.

Mugabe's fate remains unclear. He is embroiled in negotiations with the military and South African intermediaries.

Still clinging to his now-powerless post, the longtime leader was scheduled today to discuss his expected exit with the military command that put him under house arrest.

But Saturday's demonstration nevertheless sent a signal that opposition to his rule is widespread and diverse.

The rally had the air of collective catharsis. For decades, Mugabe had targeted a broad array of his own citizens: white farmers whose land was seized; political activists who were arrested or simply vanished; even Harare's street vendors, who Mugabe has tried to evict.

Members of those groups, and many others, converged on the country's State House, waving flags and signs that read, "Mugabe must go."

"If we had tried this three weeks ago, hundreds of people would have been dead in the street," resident Terry Angelos said.

It was the first time in decades that Zimbabweans had been able to protest Mugabe without fear of arrest.

"It's like our second independence day," Martin Matanisa said. "For a while it's just been oppression. This is the first time we've been able to stand here and protest."

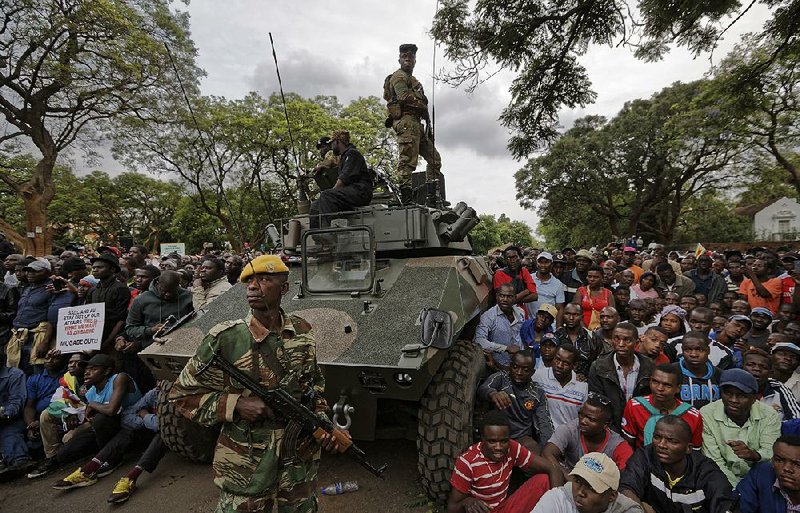

Across the city, soldiers in armored personnel carriers observed the demonstrations, not intervening. They were greeted and praised. Some posed for selfies.

"Zimbabwe's army is the voice of the people," one popular sign read.

When Maj. Gen. Sibusiso Moyo arrived to address the crowd, thousands of people grew quiet. It was clear that they were waiting for an announcement that Mugabe had agreed to step down.

"We are proud of what you have done and the solidarity you have shown," Moyo said. "But you can't achieve everything in one day."

With each day, it has become increasingly clear that if Mugabe does step down, it will be through a tense negotiation. The military has said it will not push him out by force.

Still, the demonstration was a step in Zimbabwe's move away from the 93-year-old president, the world's oldest head of state. He was once seen as a hero of Zimbabwe's liberation from colonialism, serenaded in 1980 by reggae icon Bob Marley, who wrote the song "Zimbabwe" about the country's struggle for independence.

The euphoria, however, will eventually subside, and much depends on the behind-the-scenes maneuvering to get Mugabe to officially resign, jump-start a new leadership that could seek to be inclusive and reduce perceptions that the military staged a coup against Mugabe. The president was to meet military commanders today in a second round of talks, state broadcaster ZBC reported.

Under Mugabe's watch, the economy has imploded, leaving 95 percent of the workforce unemployed, according to Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions estimates, and forcing as many as 3 million people into exile. His swift and legal exit would enable the military to implement its plan to install a transitional government until elections can be held, without the risk of outside intervention.

On Saturday, demonstrators tore down the sign from Robert Mugabe Road and stomped on it. At Zimbabwe Grounds, where Mugabe gave his first independence day speech in 1980, thousands of his opponents gathered.

Members of Zimbabwe's white minority joined the protests, many of them having lost their farms in violent government-led seizures. The land was frequently redistributed to Mugabe loyalists.

Elaine Rich and her family were given two hours to flee their farm in 2004.

"I've been waiting 37 years for this," she said, carrying a Zimbabwean flag.

"I'm glad with this show of unity to force Mugabe out," said Joyce Mujuru, whom Mugabe fired as vice president in 2014.

"We have to march to State House to remove the tyrant," said Oppah Muchinguri, the current minister of water who has backed the military takeover.

Still, some Zimbabweans expressed concern that the country was offering legitimacy to military and civilian leaders with a questionable track record.

"We cannot afford to give another set of leaders a blank check or license to dictate," said Ibbo Mandaza, a Zimbabwean academic.

Mugabe's decision to fire his longtime ally and former vice president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, could have paved the way for his wife, Grace Mugabe, 52, and her supporters from a ruling party faction known as the G-40 to gain control of the southern African nation. Nicknamed "Gucci Grace" in Zimbabwe for her extravagant lifestyle, she said on Nov. 5 that she would be prepared to succeed her husband.

The military commanders responsible for detaining Mugabe appear to support Mnangagwa as Mugabe's successor. But many Zimbabweans and Western officials have raised concerns about Mnangagwa. In 2000, a U.S. diplomat in Zimbabwe sent the State Department a cable -- later released by WikiLeaks -- saying that Mnangagwa was "widely feared and despised throughout the country" and "could be an even more repressive leader" than Mugabe.

There was still no sign of Mnangagwa, whose dismissal set off the process that culminated in Mugabe's house arrest.

The military denies having orchestrated a coup and says it is only targeting "criminals" close to the president who are damaging the country. The ruling party's provincial committees singled out Finance Minister Ignatius Chombo, Higher Education Minister Jonathan Moyo and Saviour Kasukuwere, the party's political commissar, and said they should be expelled.

On Friday, the military said in a statement that "significant progress" had been made in its efforts to apprehend members of Mugabe's government who are suspected of vast corruption and other abuses.

But negotiations with Mugabe were continuing, the military added, referring obliquely to "the way forward" without explaining whether commanders were seeking Mugabe's ouster or a different kind of settlement.

Throughout the day Friday, all 10 provincial committees representing the governing party ZANU-PF voted for Mugabe to step down. The state broadcaster, now under military control, reported that party members believed Mugabe had "lost control of the party and government business due to incapacitation stemming from his advanced age." Many of those who voted had already been at odds with Mugabe.

The discussions over Mugabe's fate come ahead of a key ruling party congress next month, as well as scheduled elections next year.

The president, who is believed to be staying at his private home in Harare, a well-guarded compound known as the Blue Roof, is reported to have asked for more time in office. He has been deserted by most of his allies, with others arrested. The ruling party has turned on him, asking for a Central Committee meeting this weekend to formally pass a resolution recalling both him and his wife, who heads the women's league of the party. Impeachment is also a possibility when Parliament resumes Tuesday.

"If there is ever to be a Zimbabwean Spring, today's marches are the first green shoots," Charles Laurie, head of African analysis at Bath, U.K.-based Verisk Maplecroft, said by email. "For the first time in 37 years, Zimbabweans stood today as a united people. The mass public demonstrations are intended to ensure there is no backsliding as the notoriously wily Mugabe seeks to negotiate an exit to the unprecedented political crisis."

Information for this article was contributed by Kevin Sieff of The Washington Post; by Christopher Torchia and Farai Mutsaka of The Associated Press; and by Godfrey Marawanyika, Desmond Kumbuka and Brian Latham of Bloomberg News.

A Section on 11/19/2017