When Pixar writer and director Lee Unkrich received the green light in 2011 to develop his follow-up to Toy Story 3, the best picture nominee that made his career, his initial excitement dissolved into fear.

Unkrich, 50, hadn't caught sophomore jitters. He knew his idea for a new animated film, which eventually became Coco, had the same potential for dazzling visuals and emotional catharsis that distinguished Toy Story 3 and other hits from the Disney-owned studio.

His anxiety was personal. The story of Coco centers on Dia de los Muertos -- the festive holiday celebrated in Mexico to honor the dead -- and Unkrich, who grew up outside Cleveland, is white and has no firm connections to that country or its traditions. He worried that he would be accused of cultural appropriation and see himself condemned to a Hollywood hall of shame for filmmakers charged with abusing ethnic folklore out of ignorance or prejudice.

"The Latino community is a very vocal, strongly opinionated community," he said. "With me not being Latino myself, i knew that this project was going to come under heavy scrutiny."

Unkrich faced a dilemma. On the one hand, he believed that artists should not be restricted to "only telling stories about what they know and their own culture." But he also needed to safeguard against his ineluctable biases and blind spots, and ensure that his film didn't "lapse into cliche or stereotype."

And that was before the rise of President Donald Trump.

The choices made by the director and his collaborators suggest one model for culturally conscious filmmaking at the blockbuster level. On Coco, Pixar's 19th film and the first to feature a minority character in the lead role, Unkrich largely dispensed with the playbook used to create immersive fictional worlds such as those in Finding Nemo and Monsters, inc. instead he relied on several research trips to Mexico and the personal stories of Hispanic team members, which helped ground his fantasy realm with specific geographic and sociological roots.

The filmmakers also turned to an array of outside Hispanic cultural consultants to vet ideas and suggest new ones -- upending a long-running studio tradition of strict creative lockdown. That approach was formalized after an early misstep in 2013, when lawyers for Disney applied to trademark the phrase "Dia de los Muertos," a working title for Coco, and ignited a backlash online.

"We don't normally open up the doors to let people in to see our early screenings," Darla K. Anderson, one of the film's producers and a longtime Pixar admiral, said of working with external consultants. "But we really wanted their voice and their notes and to make sure we got all the details correct."

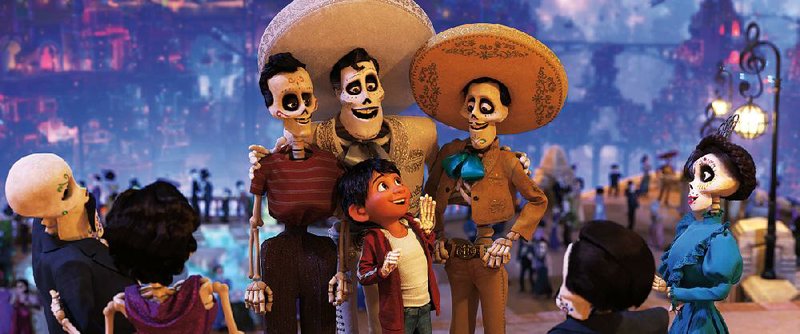

Coco tells the story of Miguel Rivera, a 12-year-old Mexican boy who dreams of becoming a famous troubadour like his idol, ernesto de la Cruz -- a guitar hero and movie star inspired by midcentury luminaries like Pedro infante and Jorge Negrete. Miguel's family sharply disapproves of music, leading to a fateful act of rebellion on the Day of the Dead that plunges him into an incandescent netherworld of walking skeletons, winged spirits and long-buried family secrets.

By seeking input on everything from character design to story early on, the studio hoped to make the movie feel more native than tourist, and to pre-empt the kind of withering, social-media-fueled whitewashing controversy that plagued the production of the Charlie Hunnam vehicle American Drug Lord more than a year ago, and helped sink films like Aloha and Ghost in the Shell. At the same time, executives trusted that non-Hispanic audiences would be drawn in by the story's universal themes of familial legacy and solidarity.

The result is brimming with small nods to daily life in Mexico, including a slack-tongued Xolo (a Mexican breed of hairless dog) as Miguel's loyal sidekick and a two-dimensional prologue animated to look like papel picado (traditional tissue-paper art).

Throughout the film, several main characters -- voiced by a nearly all-Hispanic cast that includes Gael Garcia Bernal, Benjamin Bratt and the young Anthony Gonzalez as Miguel -- slip in and out of untranslated Spanish, a rarity in commercial U.S. cinema.

"The original idea was to have the characters speak only in english with the understanding that they were really speaking in Spanish," said Octavio Solis, a Mexican-American playwright who was a consultant on the film. "But for us, language is binary, and we code-switch from english to Spanish seamlessly."

Unkrich and his team based the Rivera family -- a multigenerational matriarchy headed by Miguel's formidable abuelita, or grandmother -- on real-world families with whom they embedded while visiting the Mexican states of Oaxaca and Guanajuato between 2011 and 2013. The consultants, including Solis, cartoonist Lalo Alcaraz, media strategist Marcela Davison Aviles and a wider network of 30 to 40 volunteer advisers, played referee.

For example, in early drafts of the film, Miguel's grandmother was a coldblooded disciplinarian who kept him in line using a wooden spoon. The advisers said she felt discordant, so Unkrich softened the character and changed her chosen implement -- from a spoon to well-worn flip-flops, or "las chanclas."

"We found whenever we were made aware of these nuances and addressed them, it helped in terms of representation, but it also just helped in terms of storytelling," said Adrian Molina, who was promoted from screenwriter to co-director of Coco in 2015 and is Mexican-American.

For all of Pixar's efforts to honor the film's culturally specific origins -- and to make converts out of the 21 percent of moviegoers in the United States and Canada who identify as Hispanic -- the studio is bracing for pushback from a constituency it didn't anticipate six years ago, when President Barack Obama was on the verge of his second term in office.

The rhetoric of Trump, who disparaged Mexican immigrants and antagonized Mexico with chants of "Build the wall" during the 2016 campaign, poured gasoline on an incendiary political debate just as the film was nearing completion. Though the only borders it depicts are metaphysical (skeletal customs agents make an appearance), Coco will arrive at a moment of pitched far-right and nationalist sentiment. A February poll by the Pew Research Center showed that more than a third of Americans support building a wall between the United States and Mexico.

"It's been painful for me and a lot of people that there's been so much negativity in the world, specifically and unfairly having to do with Mexico," Unkrich said, declining to refer to Trump by name. "We're just honored and grateful that we can bring something positive and hopeful into the world that can maybe do its own small part to dissolve and erode some of the barriers that there are between us."

On at least one side of the division, the verdict on Coco is in. The film had its premiere in Mexico nearly a month ago to coincide with Dia de los Muertos, and is already the highest-grossing animated film in its history, dethroning Unkrich's previous effort, Toy Story 3, in fewer than three weeks.

"This movie is a departure, but it's a departure without making a big deal out of it," said Alex Nogales, an unpaid adviser on Coco and president and chief executive of the National Hispanic Media Coalition, a watchdog group. "They're just representing who we are."

MovieStyle on 11/24/2017