Arkansas prison officials cannot withhold labeling documents about the drugs used to concoct the state's lethal injections, a Pulaski County circuit judge ruled on Tuesday.

Judge Mackie Pierce ordered the state Department of Correction to release the materials before the end of next week unless state attorneys can get the Arkansas Supreme Court to stay his decision through an appeal.

Pierce found that the tenets of the Arkansas Freedom of Information Act trump secrecy provisions of the 2015 Method of Execution Act, the law cited by prison officials to withhold the documents from the public.

His ruling, in response to an open-records lawsuit, marks the second time a circuit judge has found that the Arkansas Code 5-4-617 does not shield drug manufacturers from public disclosure under state open-record laws.

[DEATH PENALTY: Interactive tracks allexecutions in U.S. since 1976]

"The Legislature could have easily inserted that [manufacturer] language. We wouldn't be here if they had," Pierce said. "They left out a key word that's the crux of the issue here, not once but twice."

The Legislature did describe the shielded parties in the law as "the entities and persons who compound, test, sell, or supply the drug or drugs ... medical supplies, or medical equipment for the execution process," and specifically list them as "the compounding pharmacy, testing laboratory, seller, or supplier," the judge said, citing the statute's language.

The absence of "manufacturer" in the description and list cannot be considered just an oversight since lawmakers specifically addressed the role of manufacturers in the language that sets the standards for the drugs that prison officials are required to use for lethal injection, Pierce said.

"The huge issue is -- they left the barn door open -- is manufacturers," he said. "They use it [the term manufacturer] throughout the statute. It's not like they were unfamiliar with it."

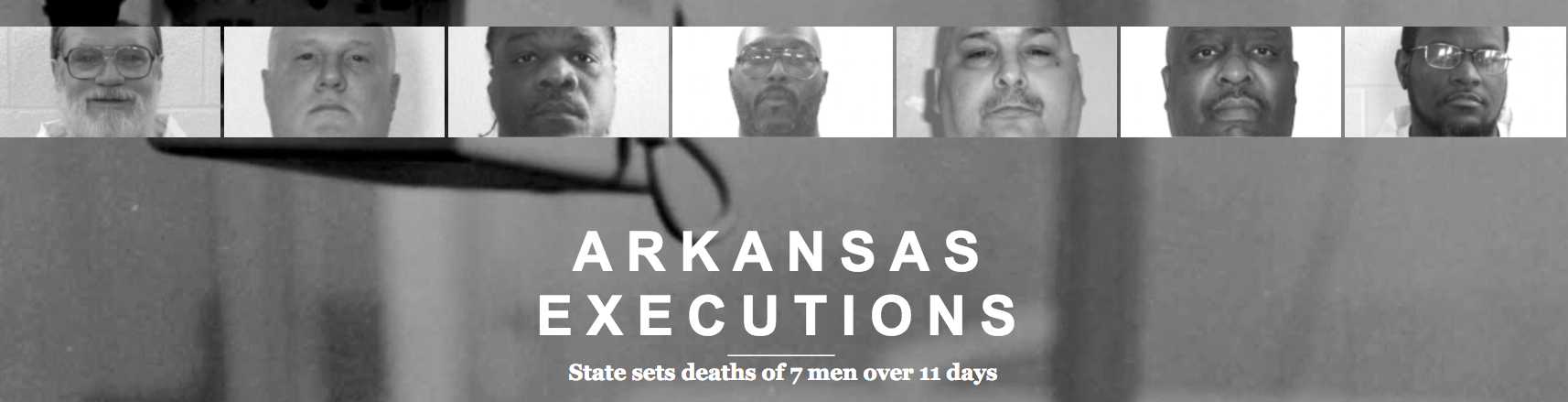

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

Pulaski County Circuit Judge Wendell Griffen reached similar conclusions six months ago. That March ruling resulted in prison officials briefly making public the labeling materials for one of the execution drugs on Griffen's orders, although state lawyers told Pierce that they only gave up a redacted version of the labels, despite Griffen stating that the documents should be released uncensored.

Pierce said he only read Griffen's findings after coming to his own conclusions by researching the execution law and studying the arguments of the attorneys. He said he substantially agreed with Griffen, describing his colleague's ruling as well-researched.

Griffen's decision is on appeal to the Arkansas Supreme Court. Pierce gave Correction Department Director Wendy Kelley until Sept. 28 to either release the complete documents or obtain a high-court stay of his ruling.

Pierce considered a shorter deadline, but state lawyers asked for nine days because they are currently working to finish their written arguments for the Supreme Court in the Griffen appeal, which are due Thursday.

Both of the Circuit Court rulings were in response to open-records lawsuits by Steven Shults of Little Rock, who complained that Kelley has violated the Freedom of Information Act and the public disclosure requirements of the execution law.

Kelley did not attend Tuesday's hearing but has countered in court filings that she did her best to comply with the law. She also argues that there's no way to release the labeling documents in any form without giving away who the state's drug supplier is.

News reporters were able to figure it out last year despite receiving the censored materials as allowed under the execution law.

State lawmakers granted secrecy protections to the death-penalty drug providers because a national shortage of the chemicals required for lethal injections was keeping Arkansas officials from obtaining the compounds.

The shortage was due in part to pharmaceutical manufacturers with overseas operations refusing to sell their wares for use in executions. The drugmakers did not like the publicity that can be attached to using a vital medicine to kill because it can make patients with a medical need for the drug fearful of it.

Those who supply the drug can also be subjected to fines and penalties under European laws that bar the sale of drugs if the chemicals are going to be used for executions. Anti-death penalty activists were also working to expose drug suppliers, some of whom complained of harassment.

Prison officials told state lawmakers the only way to obtain the drugs was if the suppliers could be guaranteed no one would find out they were providing the chemicals to the state.

To reach his conclusions on Tuesday, the judge had to decide which of the competing statutes, the execution or open-record laws, had precedence. To make that determination, court rules require that he first do everything he can to interpret the laws in a way that makes them work in harmony before he can consider giving one statute precedence over another.

Shults' attorney, Alec Gaines, argued that the most sensible way to decide which law should prevail was to interpret the public disclosure provisions of the execution law through the standard set by the Freedom of Information Act.

The open-records law requires that every state statute be "liberally construed in favor of disclosure," Gaines told the judge, citing the law, Arkansas Code 25-19-102. Examining the execution law in that manner leads to the conclusion that the statute only shields the identity of the immediate provider of the drugs to the Correction Department, Gaines told the judge.

Lawmakers obviously agreed that some disclosure was allowable because they included such provisions in the execution-drug law, Gaines told the judge.

To give credence to the state's position that the law requires keeping anything that could identify any part of the entire supply chain secret from the public would render those disclosure provisions meaningless, Gaines said. But a law cannot be interpreted to contradict itself, he said.

Representing the prisons department, Senior Assistant Attorney General Jennifer Merritt argued that the proper way to decide the case was for the judge to give preference to the more recent execution law, which was passed last year, over the 50-year-old Freedom of Information Act.

Looking at the laws as prison officials do makes the most sense to comply with the goal of the Legislature, which is ensuring that Arkansas has a steady supply of the three drugs used for lethal injections, she said.

Acknowledging that the law could have been better written, Merritt said manufacturers do not have to be specifically included in the list of shielded entities for them to receive the secrecy protections of the law.

She told the judge that for 100 years, Arkansas courts have been interpreting that language from the statute to include manufacturers in the definition of suppliers.

She also argued that the case should be dismissed, offering the judge an argument recently put forward by Attorney General Leslie Rutledge.

The Republican attorney general, in pleadings to the Arkansas Supreme Court, argues that the state constitution's sovereign immunity protections absolutely bar any kind of state-court lawsuit against the government, unless there's proof that the state officials are acting illegally.

Laws that allow residents to sue state agencies, like the Arkansas Whistle-Blower Act and the Freedom of Information Act, are only permissible because the General Assembly has written statutes that waive sovereign immunity and allow the state to be subjected to such litigation.

But Rutledge argues that lawmakers do not have that power. She contends that the state constitution strictly bars the Legislature from waiving the immunity provisions described in Article 5, Section 20, of the state constitution.

Gaines told the judge that such an argument would "gut" the Freedom of Information Act.

Shults' March lawsuit was an effort to obtain the labeling information for the state's supply of potassium chloride, the heart-stopping chemical that is the most lethal of the three drugs and, critics say, the most likely to inflict illegal pain and suffering on the condemned killers.

His current suit is about Arkansas' brand-new supply of the sedative midazolam. It's the first chemical injected and is used to prevent the inmates from feeling the effects of the killing drugs, the chloride and the paralytic vecuronium bromide.

State prison authorities announced in August that they had acquired a new batch of midazolam to replace the expired supply, allowing the state to resume executions. The only execution scheduled is set for Nov. 9.

A Section on 09/20/2017