The road to sainthood can last many years, but an Oklahoma priest and the first American-born male martyr will take the final step required before canonization today when the rite of beatification is performed in his honor before an audience of thousands.

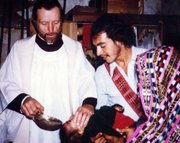

The Rev. Stanley Rother was 46 when he was killed July 28, 1981, while on mission in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala. He had served the Catholic community there for 13 years, and his death occurred in the midst of a decadeslong civil war that raged from 1960-96.

The people whom Rother lived among and served began calling for him to be honored by the Catholic Church shortly after his death, but it wasn't until the case for Rother's beatification was transferred to the Oklahoma City diocese in 2007 that Bishop Anthony Taylor of the Little Rock diocese -- who in 1981 was a priest based just outside of Oklahoma City -- became the first Episcopal delegate for Rother's cause.

CAUGHT UP IN WAR

Stanley Francis Rother was born March 27, 1935, the oldest of four children, and was raised on the family's farm in Okarche, Okla.

He completed seminary school at Mount St. Mary's University in Emmitsburg, Md., and was ordained in 1963, serving in an Oklahoma parish for five years before volunteering for the diocese's Guatemala mission in 1968.

Taylor met Rother only once, but he still remembers the day. It was May 16, 1981, and the occasion was the ordination of Don Wolf, a cousin of Rother's, into the Catholic priesthood.

"He was always a quiet person, and it was just a simple greeting [we exchanged]," Taylor said of their brief meeting. "He looked like he had the weight of the world on his shoulders."

Taylor said the Protestant churches that dominated the area tended to be aligned with the military. The Catholic Church, which had made inroads educating and bringing the nation's poorer populations into the faith, had unwittingly made itself a target during Guatemala's civil war.

Rother's death had become a direct objective in the war. He was at his cousin's ordination with the knowledge that his name was on a hit list of Catholic priests in Guatemala.

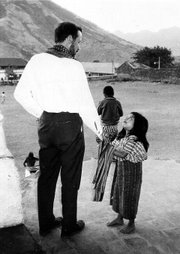

It wasn't until Taylor undertook the cause for Rother's beatification in 2007 that he learned more about Rother directly from the Tzutujil of Santiago Atitlan, an indigenous population descended from the Mayans.

"[The Tzutujil] said that [Rother] was concerned about their material welfare as well as their spiritual welfare," said Taylor, who learned that Rother had drawn from his experience growing up in Oklahoma to create farming and irrigation systems.

The Tzutujil, who numbered in the thousands, were subject to a greatly reduced life expectancy because of poverty and a lack of access to food and clean water.

MORTALITY RATE CUT IN HALF

Fifty percent of Santiago Atitlan's children, Taylor was told, died by the age of 5. By the time of Rother's death, that mortality rate had been cut in half.

Rother, who had struggled greatly to learn Latin while in seminary, had gone on to learn Spanish and then Tzutujil -- the residents' native, unwritten language.

Archbishop Paul Coakley of the Oklahoma City diocese noted that Rother's command of Tzutujil reached a level that no other priest in the Oklahoma mission to Guatemala had achieved, and possibly surpassed his command of the Spanish language.

Coakley, who had been studying at Mount St. Mary's -- of which Rother was an alumnus -- at the time of Rother's death, said Rother's struggles with learning languages and with the dangers of living and ministering in Guatemala at that time inspired him throughout his years in seminary, as a priest and through his early years as a bishop.

"He had struggled so mightily with Latin in seminary, and here he was in Guatemala and was ministering to a people whose primary language was not even Spanish," Coakley said.

Work had begun on a translation of the New Testament into Tzutujil, but it was a project Rother undertook and completed during his time in Guatemala, along with the Mass, giving people access to Scripture and Eucharist in their own language and providing religious instruction to them in their own language.

Speaking via Oklahoma City diocese spokesman Diane Clay, Rother's sister, Marita Rother, recalled Rother's traveling down "dirty, dusty roads" to hold Mass for as few as five or six people during the two summers she spent with her brother in Guatemala.

"He was there for the people; that was just so obvious," said Marita, who is a nun with the Adorers of the Blood of Christ, a Roman Catholic religious community in Wichita, Kan. "[People would] come to the door, [Rother] would be in the middle of a meal and they'd say they need something. He'd jump up and do it and come back and finish his dinner.

"I think it [was] ingrained in him," Marita said. "There was always that need to serve somebody else."

It was Rother's dedication to the Tzutujil that led him to return to Santiago Atitlan, echoing the sentiments he conveyed -- not for the first time -- in a letter dated December 1980: "A shepherd cannot run from his flock."

MARTYRDOM CALLS

One of Taylor's main responsibilities as Episcopal delegate for Rother's beatification cause was coordinating and conducting interviews with people in Guatemala and the United States. Taylor conducted the Spanish and Tzutujil interviews -- of which there were about 60 -- while the Rev. Albert Bruecken handled the English-language interviews in the United States.

Taylor said the Spanish and Tzutujil interviewees were prioritized because those witnesses "were much more fragile," referring to the Tzutujil's life expectancy and because many of them had been at or near the scene the night of Rother's death, for which no one has ever been held responsible.

Once Taylor was made the bishop of the Little Rock diocese -- Arkansas' only diocese, which falls under the same ecclesiastical province as Oklahoma -- the work of Rother's beatification cause was passed to Archbishop Eusebius Beltran.

Coakley, who succeeded Beltran as archbishop, said the news of a fellow alumnus' demise was still fresh for the students when he returned for his second year of seminary at Mount St. Mary's in late August 1981.

Rother had taken to sleeping in different locations each night in the compound where he stayed to avoid detection, Coakley said. He had already planned to let himself be killed right away, rather than be tortured and reveal information that would bring danger to others.

That night in July 1981, several people forced a young man at gunpoint to lead them to where Rother was sleeping. Rother awoke but did not cry out, afraid that the nuns who also stayed in the compound would come to help him and put themselves in danger.

"There was a struggle and a scuffle," Coakley said.

SHOT TWICE IN THE HEAD

Two shots rang out, and by the time the nuns arrived Rother was dead. He had been shot twice in the head.

Once the news of Rother's death had spread, Santiago Atitlan's plaza filled with thousands of people, gathering to mourn their pastor, Coakley said. As Rother had instructed in the event of his death, the people gathered to light an Easter candle and sang Easter songs in his memory.

The Tzutujil initially resisted the removal of Rother's body for burial in Oklahoma.

"To [the people], he was their father. They considered him one of their own," Taylor said. "He wasn't a foreign visionary [trying] to bring foreign things to them. He brought to them the Gospel in a way that connects them and their culture, and it's because he invested himself in their culture that really helped [Rother connect]. And they made him one of their own."

An arrangement was reached. Rother's heart and the cloth he had with him the night he was killed would remain in Guatemala, while his body would be returned to the United States for burial in the Rother family plot.

Although the cause for Rother's beatification was begun in 2007, it wasn't until December that he was proclaimed a martyr. Pope Francis issued the decree clearing the path for Rother's beatification. Rother had met the criteria for martyrdom: He had put himself in danger with the need to do so, he had been killed violently, and he had been killed as a result of religious hatred.

THOUSANDS EXPECTED

Cardinal Angelo Amato of Italy, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints prefect, will serve as the papal representative for Pope Francis at Rother's beatification ceremony. Representatives from the parish in Guatemala will be present, along with more than 50 bishops from around the world, and thousands are expected to attend the free event. Parts of the program, such as the Mass, will be read in English and Spanish, and parts of the program will be read in Tzutujil, melding cultures in a celebration of Rother's love and legacy.

"He was a very ordinary man, a very good man," Coakley said of Rother. "But it was God's grace that really transformed him. ... Stan overcame so much in his life and achieved so much because of this simple fidelity to God, prompting God's grace in his life."

Marita Rother said her brother's recognition by the Catholic Church makes him a modern-day religious figure that people can better relate and aspire to.

"Someone commented on the fact that children look at pictures of saints, and they're usually the saints of 14th, 15th, or first and second centuries," Marita said. "But [a] little boy saw a picture of someone that looked kind of modern and said, 'Oh, so we could be a saint too!'

"I think it's very timely that we have somebody now that can be that."

Nathan Ashburn, a fourth-year seminary student in Little Rock, headed to Oklahoma City on Friday with a group of fellow seminarians to witness the beatification rite at Oklahoma City's Cox Convention Center.

In addition to reading about and learning about Rother, Ashburn was one of the seminarians who ventured to Guatemala last year to commemorate the 35th anniversary of Rother's death. About 7,000 people -- half of Santiago Atitlan, he said -- turned out for the commemoration ceremony.

"Reading ... [about] how [Rother] struggled with school relates to me, because he struggled with Latin, and so did I for two semesters," said Ashburn, who said seminarians in the Little Rock diocese must learn Spanish to become an ordained priest.

He sees Rother as a relatable figure whose connection and selflessness make him a role model for all people.

"The idea of being all in for the people is for everyone," Ashburn said. "It's not just Catholics, it's not just Christians. It's just [that] you're all in for everyone who needs your help."

Religion on 09/23/2017