Why would NASA and a number of news outlets announce that identical-twin astronauts Scott and Mark Kelly are still twins?

It doesn't take a rocket scientist to know that even though Scott Kelly spent a year in orbit, such experiences don't change people's biological relationships. A couple can decide to no longer be husband and wife, sure -- but how could space de-relate you from your parents, siblings or twin?

It turns out NASA's statement of the obvious was fallout from a bad case of mangled science communication. It started with an attempt on the part of the space agency to drum up publicity for some ongoing research about how Scott Kelly's year-long stint in space affected his physiology.

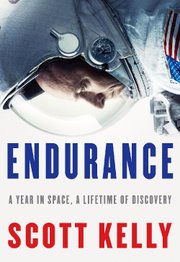

It was an appealing story not only because he broke the record for long-duration space flight, but because scientists were able to compare samples of his blood, saliva and urine with his twin brother's -- "the perfect nature versus nurture study," as NASA described it. In promoting the research, NASA also introduced people to the term "space gene."

But in the end, the episode carried lessons for scientists about the hazards of attempting to coin new scientific jargon.

Earlier this year, many news organizations reported a "space gene" had mysteriously become activated and caused Scott Kelly's genetic code to change. How this happened was not explained.

The news prompted both Mark and Scott to tweet that they no longer had to call the other an identical twin brother. This was, in all likelihood, a joke, since the twins are known for this sort of banter. But the humor might have been lost on the Today show and others that turned the alleged de-twinning of the Kelly brothers into serious news.

The problem looks to have started with a NASA news release which, after a lot of puffery about how "ground-breaking" the study was, said the following:

"Another interesting finding concerned what some call the 'space gene' ... Researchers now know that 93 percent of Scott's genes returned to normal after landing. However, the remaining 7 percent point to possible longer term changes in genes."

The release has since been overhauled, as have many of the web-based news stories, but I saved a PDF of the original. It has the distinctive quality of sounding like it should make sense, but not actually making sense.

One follow-up story informed readers that "space genes" is a "new term and is still being defined."

Another said it was "not a thing."

Geneticist Christopher Mason, who leads one of the teams that's studying the twins' genes, told me that he invented the phrase, hoping it would catch on.

Its debut has been inauspicious, as Mason knows all too well. He even sent me a link to a take-down on The Daily Show. Host Trevor Noah called the term lazy.

60,000-7=?

The original NASA news release doesn't define "space gene," but introduces it as if the reader is supposed to know what it means.

Mason said he meant for the term to apply to all the genes affected by space flight -- 7 percent of Kelly's approximately 60,000 -- but for some reason, NASA's news releases added to the confusion by referring to a singular space gene.

In retrospect, if Mason wanted to introduce the term in NASA press materials, he should have included a clear definition.

As for what actually happened to Scott Kelly's DNA, it's understandable that some journalists would assume there were mutations in it. There probably are.

It's been known for years that outside the protection of earth's atmosphere and magnetic field, astronauts are vulnerable to DNA-damaging radiation that can come from galactic cosmic rays and powerful solar flares. Excessive DNA damage can cause cells to become malignant. People develop mutations here on Earth, too, especially in cells that divide fast or are exposed to the sun.

You have copies of your DNA in most of your trillions of cells, and some of it gets damaged over time.

Mason said that indeed researchers are trying to get a measure of how space flight changes mutation rates. But they aren't releasing any data on that at this time.

As it turns out, the news release in question was supposed to be about something called gene expression.

Gene expression -- a real scientific term -- is what explains how bone and skin and liver cells hold the same DNA but do different things. Environmental influences can change gene expression in different cells, and this can influence human health.

But is the 7 percent touted in NASA's news release a big deal?

The researchers say they need more data to know how much gene expression would differ between identical twins under normal circumstances -- or how much they might differ if one trained for marathon, or went on a diet, or got a virus. The scientists don't yet know what caused the change in gene expression. Some of the change might be related to the effects of microgravity, others to sleep disruption or radiation exposure.

Some might have nothing to do with space.

In retrospect, it would have been better to emphasize the term "gene expression" in the news release, so reporters unfamiliar with the concept would at least know what they didn't know. Communication experts sometimes warn scientists to avoid technical jargon and instead to come up with catchy phrases -- like "space gene." That's good advice if your goal is to get breathless coverage on Today. But if you want genuine understanding, you might have some follow-up explaining to do.

ActiveStyle on 04/23/2018