ACCRA, Ghana -- A hush fell on the streets of the capital Saturday as the West African nation of Ghana mourned Kofi Annan, the grandson of tribal chiefs and the first black African to assume the world's top diplomatic post.

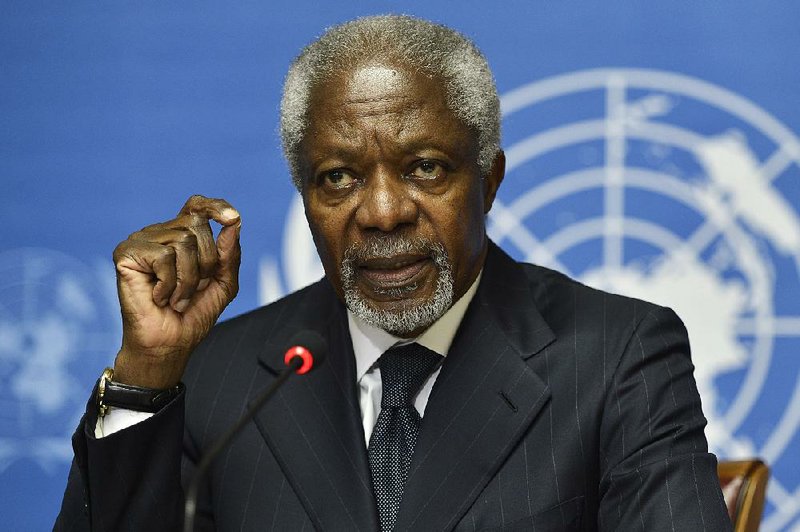

Annan died Saturday in Bern, Switzerland, at age 80. He was a soft-spoken diplomat who became the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations, projecting himself and his organization as the world's conscience and moral arbiter despite bloody debacles that stained his record as a peacekeeper.

His death, at a hospital in Bern, was confirmed by his family in a statement released by the Kofi Annan Foundation, which is based in Switzerland. It said he died after a short illness but did not specify the cause.

President Nana Akufo-Addo of Ghana ordered flags to fly at half-staff for a week while trying to reassure the country's 28 million people that the former U.N. secretary-general and Nobel Peace Prize winner died without pain.

"I am comforted ... that he died peacefully in his sleep," the president said on Twitter after speaking with Annan's wife. "Rest in perfect peace, Kofi. You have earned it."

The normally vibrant capital, Accra, was somber after initial disbelief from some residents who dismissed Annan's death as fake news.

"It was a great shock to hear this news," former President John Kufuor said. He said Annan had continued to visit Ghana about three times a year, adding that if there were any invitations, he honored them.

"Grandpa used to tell us a lot about how he was such a nice person," said Kojo Manu, a mechanic who said his late grandfather had lived in the same neighborhood as Annan.

"Big man Kofi Annan gave some of us a reason to live and to continue to have faith in our roots as Africans," said Emmanuel Youri, an advertising executive.

"He was a great African by every standard," lawmaker Ras Mubarak said.

A CHANGING WORLD

Annan was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001, with the Nobel committee calling him Africa's foremost diplomat. He led the U.N. for two successive five-year terms beginning in 1997 -- a decade of turmoil that challenged the international body and redefined its place in a changing world.

On Annan's watch, al-Qaida struck New York and Washington, the United States invaded Iraq, and Western policymakers turned their sights from the Cold War to globalization and the struggle with Islamic militancy.

An emblem as much of the U.N.'s most ingrained flaws as of its grandest aspirations, Annan was the first secretary-general to be chosen from among the international civil servants who make up the organization's bureaucracy.

He came to be likened in stature to Dag Hammarskjold, the second secretary-general, who died in a mysterious plane crash in Africa in 1961. Annan was credited with revitalizing the U.N.'s institutions, shaping what he called a new "norm of humanitarian intervention," particularly in places where there was no peace for traditional peacekeepers to keep.

And he was lauded for persuading the U.S. to unblock arrears that had been withheld because of the profound misgivings about the U.N. voiced by American conservatives.

His tenure was rarely free of debate, however. In 1998, Annan traveled to Baghdad to negotiate directly with Saddam Hussein over the status of U.N. weapons inspections, winning a temporary respite in the long battle of wills with the West but raising questions about his decision to shake hands -- and even smoke cigars -- with a dictator.

Annan called the 2003 invasion of Iraq illegal and suffered a personal loss when a trusted and close associate, the Brazilian official Sergio Vieira de Mello, his representative in Baghdad, died in a suicide truck bombing in August 2003 that targeted the U.N. office there, killing many civilians.

The attack prompted complaints that Annan had not grasped the perils facing his subordinates after the ouster of Saddam.

While his admirers praised his courtly, charismatic and measured approach, Annan was hamstrung by his position as what many people called a "secular pope" -- a figure of moral authority bereft of the means other than persuasion to enforce the high standards he articulated.

As secretary-general, Annan, like all his predecessors and successors, commanded no divisions of troops or independent sources of income. Ultimately, his writ extended only as far as the usually squabbling powers making up the Security Council -- the highest U.N. executive body -- allowed it to run.

In his time, those divisions deepened, reaching a nadir in the invasion of Iraq. Over his objections, the campaign went ahead on the U.S. and British premise that it was meant to disarm the Iraqi regime of chemical weapons, which it did not have or which were never found.

In assessing his broader record, moreover, many critics singled out Annan's personal role as head of the U.N. peacekeeping operations from 1993-97 -- a period that saw the killing of 18 U.S. service personnel in Somalia in October 1993, the deaths of more than 800,000 Rwandans in the genocide of 1994, and the massacre of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims by Bosnian Serb forces at Srebrenica in 1995.

In Rwanda and Bosnia, U.N. forces drawn from across the organization's member states were outgunned and showed little resolve. In both cases, troops from Europe were quick to abandon their missions. And in both cases, Annan was accused of failing to safeguard those who had looked to U.N. soldiers for protection.

EFFORTS IN AFRICA

Annan was born April 8, 1938, in the city of Kumasi in the Ashanti heartland, two decades before Ghana became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to gain independence from colonial rule.

The son of a provincial governor, he attended an elite boarding school and became fluent in English, French and several African languages and quickly entered the diplomatic world.

Most of Annan's working life was spent in the corridors and conference rooms of the U.N. But, he told author Philip Gourevitch in 2003, "I feel profoundly African, my roots are deeply African, and the things I was taught as a child are very important to me."

Africa's widespread health and development challenges shaped Annan's crafting of what became known as the Millennium Development Goals and played a central role in the creation of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

After stepping down as U.N. chief, Annan was still called on to apply his diplomatic skills to some of Africa's biggest crises, either on his own or as chairman of The Elders, a group of former leaders founded by South Africa's Nelson Mandela.

On Saturday, Kenyan opposition leader Raila Odinga said he had "fond memories" of Annan because he stepped in to save the country from civil war after a flawed presidential election in 2007 that led to more than 1,000 deaths. Annan brokered a power-sharing deal to calm tensions.

Annan also spoke sharply at times about the continent and its ills, saying late last year on Twitter that "the African officials who are signing away their countries' resources at an almost giveaway rate to big multinationals in the expectation that they will get something are really betraying their people. It denies them development and food."

Annan's last major public appearance in Africa was last month in Zimbabwe before a historic presidential election, the first without longtime leader Robert Mugabe on the ballot.

As Annan urged Zimbabweans to vote peacefully and met with the country's leaders, he struggled to walk and coughed from time to time, with his aides closely following behind.

"Annan's origin and home will always be traced to Ghana, but his exceptional leadership roles, humanitarian spirit and contributions to global peace and development will remain indelible in the history of the entire world," President Muhammadu Buhari, the leader of another West African power, Nigeria, said Saturday.

Information for this article was contributed by Francis Kokutse, Tom Odula and Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi of The Associated Press; and by Alan Cowell of The New York Times.

A Section on 08/19/2018