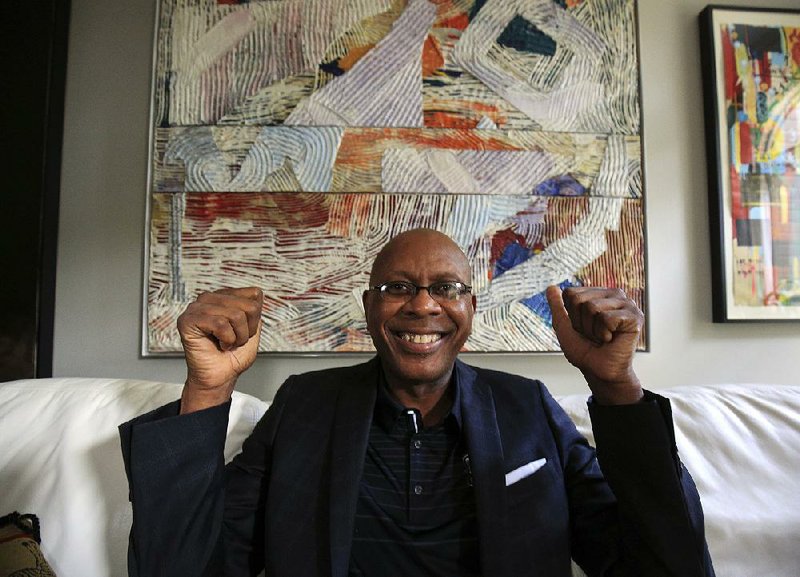

It's hard to pay attention to University of Arkansas at Little Rock head basketball Coach Darrell Walker as he talks while sitting on a white couch in the living room of his Little Rock home.

Not that what he's saying isn't interesting -- it is, very much so -- but it's difficult not to look to the left at the large canvas of a dancing woman painted by the acclaimed British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, or gaze behind Walker at the colorful Sam Gilliam abstract piece on the wall over the couch or at the Radcliffe Bailey mixed media image to the right.

And you know there's more because Walker, the 57-year-old former Arkansas Razorback, 10-year National Basketball Association veteran and longtime coach who was hired by UALR in March, is a passionate collector of art and has acquired an impressive assemblage of pieces made mostly by black artists.

"I love waking up and walking through the house looking at the works that we have here," he says. "It's something I can pass down to my kids and my grandkids. It's our culture, it's African American culture and it's a treasure to me. It's a big part of my life, and I've been doing it for a long time."

Walker grew up on the south side of Chicago -- "in the projects, violence, drugs, the usual inner city stuff," he says. He played basketball at Westark Community College, now the University of Arkansas-Fort Smith, and then played for Eddie Sutton at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

Walker would become the Razorbacks' 18th leading scorer and is ranked fourth in steals and sixth in free throws made.

In 1983, he was drafted 12th overall by the New York Knicks and became a teammate of Bernard King, who would eventually lead Walker into the art world.

But not right away.

"Bernard was one of the greatest players I've ever played with," Walker says. "He tried to get me into art when I was a young kid, but at that time I was in New York, having fun, trying to get into Studio 54 and hang out."

A few years later, when the two were playing for the Denver Nuggets, King's talk about art started to sink in.

"I would sit with him on the airplane during road trips and he would show me parts of his art collection and talk to me about art and why I should collect."

Walker started collecting seriously in the early '90s. His first pieces were bought from George N'Namdi's gallery, then in Birmingham, Mich. (now in Detroit), and included Jacob Lawrence's serigraph The Birth of Toussaint L'Ouverture, Romare Bearden's lithograph The Open Door and a painting on paper by Robert Colescott.

"Robert deals with a lot of racial stereotypes," Walker says while standing in front of the Colescott piece, titled My Momma Done Told Me, at his home.

He got to meet Colescott, who died in 2009, when he bought the painting.

"It's always special when you can meet the artist," he says.

He visited with Yiadom-Boakye a few years ago at her London studio.

"I was assistant coach with the Knicks and we were playing the [Detroit] Pistons over there," Walker remembers. "I went to her studio and hung out with her. I gave her tickets to the game and that was the first time she'd ever been to a basketball game."

He also befriended painter Jacob Lawrence, who died in 2000, and abstract artist Sam Gilliam.

"I've built a really good relationship with Sam Gilliam. When I was coaching in Washington, D.C., I'd go to the studio and hang out with him."

Walker and the 84-year-old Gilliam were together in Washington earlier this month, actually.

"He is a helluva artist," Walker says. "His work is powerful, colorful, vibrant. It really speaks for itself."

Walker has donated two works by Gilliam, who was part of the color field movement, to the Arkansas Arts Center and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville.

Former arts center executive director Todd Herman says the Gilliam piece, Black Frost, is a boon to the center.

"Sam Gilliam is an important abstract African American artist, and having a work by him in the collection, in any collection that tries to tell the story of American art, is very important."

Herman and Walker became friends after Herman came to the arts center seven years ago.

"He's an outstanding collector, and he is always finding new artists," says Herman, who recently left the center to be chief executive at The Mint Museum in Charlotte, N.C.

. . .

Walker and his wife, Lisa, who also collects art, have five children and four grandchildren. Little Rock has been home base for them since 1983.

But his career as an NBA player and coach and later as a college coach means that he has spent a good part of his adult life traveling, and he has built a network of friends among gallery owners, artists and fellow collectors.

"It became my outlet on the road, to go to museums," he says. "I take artists out to dinner and before you know it, years go by, you wind up amassing a huge collection. My wife says all the time that through this art world, we have created a whole new set of friends."

Herman says that Walker has a habit of checking in from the road with a new art find.

"Fairly regularly I'll get a text from Darrell and he's somewhere in the country and has come across an artist he thinks deserves a look."

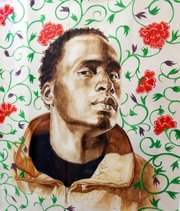

In 2013, Walker saw the work of a young Baltimore painter named Amy Sherald. When he learned that she wasn't represented by a gallery, he called his friend Monique Meloche, owner of Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago.

"He said, 'She's not fully formed yet, but I've got this artist you should be looking at,'" Meloche recalls.

In 2015, Meloche invited Sherald to be in a group show at her gallery, which focuses on contemporary art by artists of color.

"When the first painting arrived we were spellbound," Meloche says. "When she arrived I told her that we needed to represent her, and we gave her her first solo show the next year."

This year, Sherald painted the official portrait of former first lady Michelle Obama for the National Portrait Gallery.

"Darrell has a tremendous eye," Meloche says. "He's always looking for what young, contemporary artists are doing. I definitely listen to him."

Walker doesn't own a work by Sherald, but he does own one by Kehinde Wiley, who painted former President Barack Obama's official portrait.

His collection, which numbers around 80 pieces, is an eclectic mix that features midcentury and contemporary works and includes sculpture, paintings, drawings, photography, collages, mixed media and more.

There's a Beauford Delaney; a graceful, powerful bust by Elizabeth Catlett; a Jeff Sonhouse image made in part with burnt matches; a photo and powerful accompanying text by MacArthur Foundation Grant award winner Carrie Mae Weems; a Lois Mailou Jones watercolor; Demetrius Oliver's brutal, sobering photograph Till, inspired by the 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till; an intense charcoal drawing by Pine Bluff's Henri Linton; an acrylic on plexiglass piece by Alvin Loving; a spare, elegant Richard Hunt sculpture of two dancers on a table beneath Calvin Burnett's ink on paper drawing Lovers and on and on.

(Don't bother being gauche and asking what it's all worth or how much is the most expensive piece. Walker just smiles and declines to answer.)

In his home office hangs a poster-size photo called Basketball and Chain by New York-based conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas. The image shows a chain stretched from a basketball and connected to the ankle of a player wearing Nikes and soaring above the ball.

Explaining what it means to him, Walker, whose professional life revolves around the sport, says that "it's talking about athletes, basketball players, and not letting themselves become slaves to the game. Don't let the game use you."

. . .

When he started collecting, Walker leaned toward figurative work. Abstraction was, well, too abstract.

That all changed when he found his first Norman Lewis.

Lewis was a New York City-based painter and contemporary of Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Ad Reinhardt and other abstract expressionists in the '40s and '50s.

"There's a photograph from Life magazine," Walker says. "They were at the Cedar Tavern [in New York City's Greenwich Village] -- de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline -- and Norman Lewis was at the table with them."

But Lewis, who died in 1979, never got the attention the white artists did and struggled for years.

"To be in that group and sit at that table and see them take off and sell for millions and you never see a piece sell for over $10,000 in your whole life before you die, you'd be a bitter guy. But he kept painting and he kept working."

Walker is standing before an untitled Lewis work, one of three he owns. The oil, pen and ink image on paper has a light blue background with clusters of black markings.

"This was the first time an abstract piece hit me. I said, 'I'm buying this' and I'm so glad I did. You can see different things in it. It's a great Norman Lewis piece."

Walker's preferences continue to grow. He points to a round sign, a sort of pop art piece advertising The Association of Named Negro American Potters by Theaster Gates of Chicago.

"Years ago, I would have never bought that," Walker says. "I would have laughed at that, but my taste has changed."

Walker, like his mentor King, also spreads the art-collecting word to fellow athletes.

Elliott Perry of Memphis, who played 11 years in the NBA, started talking art with Walker on an NBA trip to China in the mid '90s. Perry has since amassed his own impressive collection.

"He has one of the best collections of African American art in the world," Walker says.

"I didn't know anything about art until I met Darrell," says Perry, a Memphis native. "He piqued my interest and then followed up and kept me engaged and helped me navigate through how to collect. We spent time going to shows and art fairs and my interest increased more and more."

Perry says the collecting they do "is like we're curating culture and heritage. We're supporting that. When people look back, they will see a mighty journey from the work that Darrell has collected and the impact that he has had on art and artists and people."

Walker stresses that beginning collectors should buy what moves them, but they should also learn about what they are buying.

"It's very important that they study. Go to museums, go to art openings, spend time reading," he says. "Read about art and just observe. Just look, see what attracts you, go to galleries, go to the openings and hang out."

The collecting bug has caught on. NBA players like Caris LeVert and Carmelo Anthony and former players like Juwan Howard and Grant Hill, among others, have put together notable collections and entrepreneur and rapper Sean "P. Diddy" Combs recently paid $21 million for Kerry James Marshall's painting Past Times.

(Walker still rues the day years ago when he passed on a $60,000 Marshall drawing. "It was pretty nice-sized work, and I didn't pull the trigger," he says.)

"I think it fascinates some people that athletes can collect at that level," Perry says. "You're starting to see others like Jay-Z, [rapper] Swizz Beatz, Beyonce, Oprah -- a lot of the artists they're collecting now, we've been singing those artists' praises for 20-25 years."

. . .

There are certainly big chunks of money passed around at the high end of the art universe, but Walker sees collecting as something more than a financial investment. A work of art has to appeal first to his tastes.

"You buy what you like," he says. "I look at it as something to get pleasure from. But if it goes up, moneywise, that's even better."

Has he ever thought about leaving courtside and buying and selling art as a full-time gig?

"The people that I know in the business world, the sports world, entertainment, I could probably make a good living," he muses. "But I'm a basketball coach. That's what I am. A basketball coach who is also an art collector."

Style on 08/19/2018