"We wanted Music From Big Pink to sound like nothing anyone else was doing. This was our music, honed in isolation from the radio and contemporary trends."

-- Levon Helm, in his 1993 memoir This Wheel's on Fire

Nostalgia isn't our best look. It's a soothing lie we tell ourselves. The past is a legend, warped by the wishful fantasies of its retellers. We can make the evidence say whatever we need it to say.

Maybe it would have been a good project to spend this year focusing on 1968. It seems that every week brings the 50th anniversary of some national trauma. That was the year when something broke deep in a seemingly exhausted American experiment.

It was the year of James Earl Ray and Sirhan Sirhan and Cmdr. Lloyd Bucher, captain of the USS Pueblo, who surrendered his ship to the North Koreans. The year of the Tet Offensive and the My Lai massacre. The year Walter Cronkite took off his glasses and looked into the camera to say: "It now seems more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate. To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe in the face of the evidence the optimists who have been wrong in the past ... it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could."

It was the year The Beatles recorded "Revolution," and the Rolling Stones released "Street Fightin' Man:": Everywhere I hear the sound of marching, charging feet, boy/ Cause summer's here and the time is right for fighting in the street, boy. Otis Redding died. The Byrds released the ticking time bomb that was Sweetheart of the Rodeo.

And in the basement of an 1,850-square-foot split-level (three bedrooms, two baths, sleeps six, currently renting for $471 a night) in West Saugerties, N.Y., music brown and eerie as a sepia photograph was being brewed.

That music became Music From Big Pink. It was released approximately 50 years ago, on July 1, 1968.

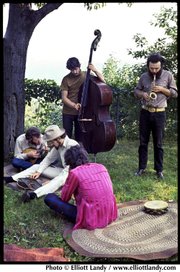

On Friday, several new iterations of the the record will be released. It has been spruced up with a new stereo mix on CD and digital with five outtakes, alternate recordings and an unreleased a cappella version of "I Shall Be Released." There will be a double-LP vinyl boxed set of the album, with a CD, digital access card and high-res surround mix on Blu-ray. It also includes a reproduction of the 7-inch single "The Weight" with the B-side "I Shall Be Released." There's a hardback book with an essay by David Fricke and photos by Elliott Landy.

And there's a limited-edition version on pink vinyl.

. . .

Music From Big Pink wasn't recorded in the house with the famous basement. And that rental house in the Catskills, named for its pink siding, wasn't the only place where Bob Dylan and his backing band jammed after the 1966 "motorcycle accident" that drove him into seclusion and kept him from touring for eight years.

"Motorcycle accident" in quotes, because I don't believe it. There are no records of Dylan going to a hospital, no police report. Dylan was close to his manager Albert Grossman's house (on Striebel Road, near the intersection with Route 212) when the wreck occurred; his then wife Sara was following him in a car. Sam Shepard said the sun blinded Dylan and he laid the Triumph Tiger 100 down. Dylan told writer Robert Shelton he hit an oil slick and was thrown off the bike. It's said he suffered facial lacerations, maybe a broken back, that he almost died.

Yet 1967 was one of his most productive, most creative years.

I think something happened, maybe a close call, maybe a minor crash. The real trauma was psychic. Like Dylan wrote in his memoir Chronicles: "I had been in a motorcycle accident and I'd been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race. Having children changed my life and segregated me from just about everybody and everything that was going on. Outside of my family, nothing held any real interest for me and I was seeing everything through different glasses."

But this left his band -- which wasn't yet called The Band -- in a lurch. The cancellation of 60 tour dates was a serious deal -- they couldn't afford to live in Manhattan or Los Angeles where they might have found studio work. (They played gigs supporting Tiny Tim.)

Other members of what would become The Band were making frequent trips to Canada, thinking they were going to have to find another gig soon, when Dylan invited them to his rambling cedar house on Camelot Road near the old Byrdcliff arts colony to look for places to stay. Robbie Robertson and his wife Dominique Bourgeois took up residence in Grossman's guest house.

Rick Danko found a relatively new house, with pink siding and a view of the Overlook Mountain, about five miles away. He signed the lease for $125 a month, and Garth Hudson and Richard Manuel moved in.

Meanwhile, Arkansas native Levon Helm worked on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. To earn money to live.

But he came back after Grossman convinced Capitol Records to sign the band, then known as The Crackers, to a deal of their own. And the songwriting began in earnest.

They recorded the album in January and February of 1968 in studios in Manhattan and Los Angeles, at least in part because Big Pink's basement had concrete floors, cinder block walls, and an iron stove -- not an environment conducive to recording. But it's not difficult to locate the source of what became known as alt-country or Americana in that house, to designate it one of the primal scenes of American music history. What it was, was a womb, from which the Great American Band was birthed.

. . .

It is hard to convey exactly how weird Music From Big Pink was when it was released 50 years ago; and how different The Band was from Levon and the Hawks, the rowdy professionals who backed up barnstorming Ronnie Hawkins. Those guys were ravers and hell-raisers; The Band was sui generis, one of the few rock 'n' roll bands that deserve a few paragraphs in history texts.

You can make fun of them if you go no deeper than the album cover, or the way Danko sings "kilt" as a joke on "Long Black Veil," the only cover song on Music From Big Pink, a faux Appalachian ballad inspired by the murder of a New Jersey priest and a mystery woman who allegedly paid regular visits to the grave of Rudolf Valentino by the sly pro who'd written "Big Bad John" for Jimmy Dean. There was lots of silliness in the poses adopted by pop musicians in the '60s, and The Band's wardrobe (along with Landy's Matthew Brady-style portraits) might suggest a more authentic Gary Puckett and the Union Gap. But listen to the music.

Heard today, Big Pink remains a revelation, perhaps the best debut record ever released, though The Band had been together nearly a decade by the time it came out. Most of the songs have become overly familiar, part of the hammering, inescapable baby-boom soundtrack. Still, it is important to listen, to hear how different it is from most American pop music. It integrates elements of folk, gospel, ragtime jazz, rockabilly, doo-wop, bebop, pop, country and blues into a sound thrillingly unique and comfortingly familiar, plain and strange, intimate and monumental.

Like the Velvet Underground, The Band didn't rely on standard blues progressions and like Dylan, they reached back into a collective warehouse of images from what music critic Greil Marcus has termed "the old, weird America." Their songs were narratives. The singers -- especially Helm and Danko -- assumed characters and told their stories in cinematic detail.

Maybe they are the Great American Band in part because they are mainly Canadian (and one-fifth Arkansan), which makes them only sort-of Americans, outsiders, which lent them perspective. Which let them see straight into the heart of the wounded noble land to the South. For them, all of America was the South.

Maybe we needn't get too deep into history lessons or recounting of old grievances here. Whether Robertson fairly or unfairly appropriated Helm's cultural heritage for his lyrics might be worth thinking about, but there's no way to reconcile the two camps with an essay. Some people thought Robertson took too much from his bandmates without giving them proper credit; others think he was undeniably the band's chief creative engine. Let's just notice that the divorce was ugly and that Helm held a grudge until he died in 2012.

And that Helm (born in Marvell, 1940) was the band's leader after they split from Hawkins in 1963, but Robertson was closest to Dylan. And that none of them were slouches.

Except for Robertson, who was a guitarist, they were all multi-instrumentalists. Helm was mainly the drummer but was playing guitar by the time he was 8 years old and added the mandolin soon afterward. Danko played bass, guitar, violin and trombone; Manuel played piano, harmonica, drums and sax. Hudson may have been the most accomplished -- he got an extra $10 per week as the band's music instructor -- and considered his rock 'n' roll organ playing a hobby, something to fill the time while he was preparing for a serious music career.

While they never went in for ostentatious instrument-switching on-stage, in the studio it didn't seem to matter who was playing what. Their songs could sound like a chuckwagon full of marching band instruments falling down a mountainside in a tornado, but they were also full of subtle colors, shifting timbres.

It helped that they could sing. Helm had his plaintive dirt farmer's drawl, sweat-soaked and seeded with grit; Danko a gliding, frictionless tenor and Manuel -- whom Helm and Danko considered the lead singer -- moved between a keening falsetto and a dark, murderous baritone. With occasional support from Robertson (who only sang lead on a handful of songs) they formed rough-hewn harmonies, approximate and relative but with the odd, raw beauty of a Howard Finster painting.

Robertson's guitar solos are short and sweet, little bursts of riffs rather than pealing, twisting runs. (Compare his economical work with that of Duane Allman and you might understand why Eric Clapton once aspired to become a member of The Band.)

Helm -- famously described by Jon Carroll as "the only drummer who can make you cry" -- favored loping, ragged beats that evoked the smell of blood and cordite.

There's an appealing, jug band-style looseness to the record; only the sonic fidelity argues against the songs being recorded in the 1930s. But it's not nostalgic.

It's timeless.

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.come

Style on 08/26/2018