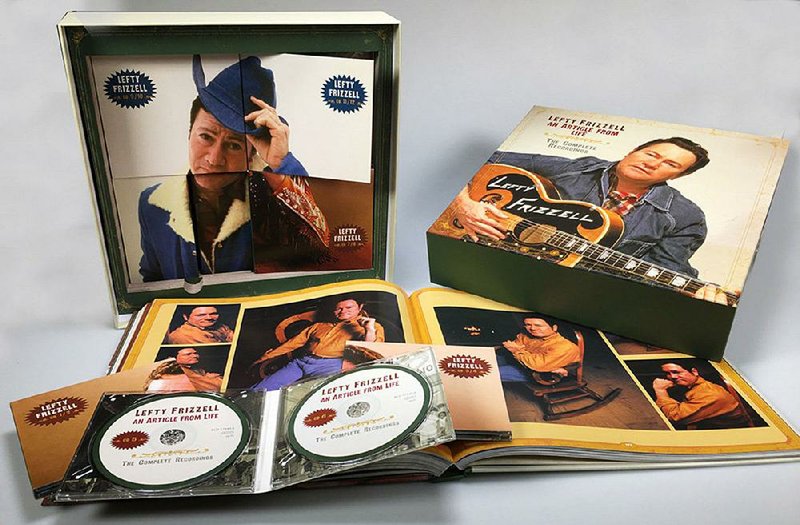

To many modern people, country singer "Lefty" Frizzell may seem obscure, and the idea of a 20-CD set presenting not only every track he's known to have recorded but nine CDs of his younger brother David -- also a notable country singer -- reading the audiobook version of his (pretty good) biography I Love You a Thousand Ways: The Lefty Frizzell Story might seem ridiculous.

The list price of An Article from Life: The Complete Recordings (Bear Family) is $299.99. It's beautifully packaged, with an "updated and revised" copy of Life's Like Poetry, Charles Wolfe's 1991 biography of the singer, augmented by hundreds of photographs.

It's a lot of music -- 361 tracks -- for a guy who had a handful and a half of hits and disappeared for long stretches during what now seems be a truncated career. Frizzell died in 1975 at age 47.

But his influence can't be tracked by numbers. He probably had as much to do with shaping the sound of vocal pop music over the past 70 years as anyone, including Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra. Many singers were deeply influenced by him -- George Jones, widely considered the greatest country singer ever, lost an early gig because the auditioners thought he was a too-blatant imitator of Frizzell. Roy Orbison adopted "Lefty" as his Traveling Wilburys name in his honor.

Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard issued tribute albums to Frizzell; crediting him as a foundational inspiration. Keith Whitley was so affected by Lefty that he recruited another of his siblings -- Allen Frizzell, a gospel artist who bills himself as The Other Brother -- to sing on the chorus of Whitley's 1987 version of Lefty's "I Never Go Around Mirrors."

Yet, outside of "If You've Got the Money, I've Got the Time," "The Long Black Veil" and maybe "Saginaw, Michigan," his records haven't obtained the canonical status as those of his contemporaries Hank Williams and Webb Pierce. As it is, Frizzell pops up here and there in the story of American country music, a kind of singer's singer. More than settling his legacy, the Bear Family set raises a question:

Why isn't Lefty more famous, more respected, more heard?

Heck, some of you are probably even asking: Why have I never heard of this Lefty Frizzell before?

. . .

Sometimes straightforward questions cannot be answered in a straightforward manner.

For instance, there are people who will tell you that the term "honky-tonk" comes from the fact that the upright pianos manufactured by an outfit called William Tonk & Brothers of Chicago and New York were popular in the brothels and bars where the music was performed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Others will cite the prevalence of these instruments among the songwriters of New York's Tin Pan Alley in the late 19th century.

But William Tonk & Brothers -- not to be confused with Tonk Manufacturing Co., the Chicago-based furniture maker the brothers established in 1871 that was once the world's largest maker of piano stools and benches -- didn't begin producing pianos until 1881, by which time the phase was apparently common enough to be understood by a general audience. It appears in the Peoria Journal in 1874: "The police spent a busy day today raiding the bagnios and honkytonks."

A Wikipedia entry speculates that since "early uses of the term in print mostly appear along a corridor roughly coinciding with cattle drive trails extending from Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas, into south-central Oklahoma, suggesting that the term may have been a localism spread by cowboys driving cattle to market. The sound of honky-tonk (or honk-a-tonk) and the types of places that were called honky-tonks suggests that the term may be an onomatopoeic reference to the loud, boisterous music and noise heard at these establishments."

That driving music, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was related to ragtime, with an emphasis on rhythm. In part this was because the pianos in the establishments where this music was played were generally cheap and poorly maintained, often out of tune with broken keys. They were more fit for pounding than for Debussy's "Arabesque No. 1."

It was regional music centered in Oklahoma, Texas, and northwestern Louisiana, with some bleed into Arkansas and New Mexico, informed by spirit more than technique, with singers shouting over the din. It was stripped down and raw and often performed by self-taught musicians. As time went on it evolved; pianos were exchanged for guitars, steel guitars and dobros, with drums coming along a little later. It was magpie music, snatching whatever it wanted from different traditions, taking, as Bob Wills said, "a little bit of this, and a little bit of that, a little bit of black and a little bit of white ... just loud enough to keep you from thinking too much and to go right on ordering the whiskey."

But if you really want to know what honky-tonk is, skip straight through to the end of World War II when, in 1945, Hank Williams left his wartime job in the shipyards of Mobile, Ala., and resumed writing songs. He was rejected when he tried out for the Grand Ole Opry, but signed a publishing deal with Acuff-Rose that led to a deal with Sterling Records and, in December 1946, his first recording session.

. . .

About the same time Williams was beginning to make something of what Roy Acuff called his "million dollar talent" (that went with his "ten-cent brain"), William Orville Frizzell, known to family and friends as Sonny, landed in Dexter, N.M. He was married, with a daughter, but was still too young to legally drink in the honky-tonks where he played guitar and sang on Saturday nights.

He'd been born in 1928 in Corsicana, in east Texas, the oldest son of a peripatetic oil patch worker. The family spent time in El Dorado, where brother David was born in 1941. Sonny married Alice Harper in Oklahoma just before he turned 17. He'd stay married to her all his life, but there were some blowups.

The most major of these came in August 1947, about the time Hank recorded "Lovesick Blues." Frizzell had become something of a local celebrity. He'd formed a dance band and graduated from playing the two-bar town of Dexter to playing the Cactus Garden Club outside the relatively big city of Roswell and the Top Hat Club, between Roswell and Carlsbad. He had a live radio show. He had groupies.

One of those groupies was 14 years old and told her daddy about what she'd got up to with "Lefty," who in all probability probably wasn't yet Lefty but still known as Sonny. The judge said six months in jail for statutory rape. Frizzell spent a lot of his jail time writing apologetic letters and poems to Alice, one of which would become "I Love You a Thousand Ways" which was the B-side to his first single, "If You've Got the Money, I've Got the Time," which was his first hit in 1950.

"I Love You a Thousand Ways" was his second hit, also in 1950. In all, Frizzell, who by then was called Lefty, landed eight singles in the Billboard Top 10 in 1950-1951.

. . .

OK, let's deal with the Lefty business. There are lots of stories about how Sonny came to be known as Lefty. His press bio used to claim that he'd acquired the nickname as a teenage prizefighter. Most accounts now say he never formally boxed but, during a schoolyard brawl, demonstrated a tidy left hook. In some tellings the other kid didn't realize Frizzell was left-handed.

Though there's no reason to doubt the fighting story, I'm dubious. Sounds like a record label myth.

On the other hand, Frizzell apparently was left-handed (though he played guitar righty) and not afraid of physical confrontation. In his book, David Frizzell recalls his brother fighting their father after the old man abused their mother.

David also mentions that Lefty abused Alice, to the point she once pulled a gun on him. (She filed for divorce three months before he died.)

Like I said, straightforward answers are elusive.

. . .

It's interesting to note, as Texas writer Michael Corcoran has in his excellent book All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music, the role technological advances played in Frizzell's success. Corcoran points out that Seeburg Corp. introduced the 45-rpm jukebox in 1950. Frizzell's songs were tailor-made for the format -- his audience consumed jukebox music and boosted his chart success.

More than that, what really helped Frizzell was the improvement in microphones during the 1940s. As Corcoran notes, "singers didn't have to shout like Roy Acuff" any more. Electric guitars and well-amplified voices changed the textures of barroom music; Frizzell's phrasing, the way he slides sinuously through a lyric, affecting a conversational, almost offhand tone, was only possible because you could hear it over the rest of the band.

Frizzell was country music's first great modern vocalist -- he and Hank Williams draw from Jimmie Rodgers' keening modal palette, the high lonesome yodel. But Frizzell was savvy enough to realize that by relaxing into his natural register, by refusing to strain to hold notes that were difficult, he produced a tone so warm and natural -- so authentic and unassuming -- that it didn't feel like a style. Frizzell's other main vocal influence was Earnest Tubb, a singer so laid back and easygoing that, one story goes, when a new musician asked him what key he was singing in, he replied, "Oh, three or four of 'em."

When you hear Haggard's sincerity or Nelson's half-talked vocal phrases, you're hearing Frizzell. When you hear Orbison, you're hearing a preternaturally gifted bel canto version of Frizzell.

When you hear Elvis Costello, you're hearing a nasal baritone version of Frizzell. It's hard to think of a pop singer from the mid-20th century onward who hasn't been profoundly influenced by Frizzell.

. . .

So Frizzell gets out of jail in Roswell, moves to Big Spring in west Texas where his band is established as a major force in the Ace of Clubs, one of those bars where they surround the performers with chicken wire to protect them from thrown bottles.

Corcoran reports Frizzell drove 180 miles to fill in for the ailing lead singer at the Ace of Clubs and was an immediate sensation ("The Ace of Clubs was his Cavern Club, his CBGB," Corcoran writes). He's invited to record in Dallas by Jim Beck, who was also interested in Frizzell as a songwriter. Beck immediately pitched "If You've Got the Money" to the label's hottest act at the time, Little Jimmy Dickens. When Dickens passed, Columbia A&R man Don Law signed Frizzell as a recording artist.

At the time, Frizzell's highest and best use seemed to be as a songwriter -- he wrote most of his early hits. From 1950 to 1953, he was arguably the biggest star in country music, scoring seven more chart hits in 1951, including "Mom and Dad's Waltz," "Travelin' Blues," and the No. 1 "Give Me More, More, More (Of Your Kisses)." He had four more chart hits in 1952, and was in demand as a concert performer, appearing on the Grand Ole Opry and Louisiana Hayride multiple times during that stretch.

But while Frizzell wrote or co-wrote most of those songs, he never came close to Williams' hillbilly poetry. Frizzell's drinking became worse -- he got arrested for "contributing to the delinquency of a minor" in Shreveport in 1951, had a suspicious automobile accident in Minden, La., in 1952 and never really got along with the establishment in Nashville, Tenn. He sued his manager in 1953 and moved to Los Angeles. While he continued to tour sporadically, he virtually stopped recording and writing.

He allegedly passed on recording Buddy Holly's "That'll Be The Day." He was allegedly too jaded to meet the up-and-coming Elvis Presley. He disappeared from the charts.

. . .

His first comeback came in 1959, when he recorded "The Long Black Veil" (which sounds like an old Appalachian ballad but was a new composition by Denny Dill and Marijohn Wilkin ). The Top 10 success encouraged him, and he moved back to Nashville in 1961. Law -- his biggest supporter in the industry -- assembled a coterie of talented sidemen including Floyd Cramer, Grady Martin and Hank Garland to play on his recordings. He scored a No. 1 hit in 1964 with "Saginaw, Michigan," a song written by Don Wayne and "Whisperin'" Bill Anderson (whose low-key vocals might be unimaginable were it not for Frizzell).

"Saginaw, Michigan" is a novelty song transformed to a near-classic by Frizzell's masterful and sly delivery. While it's basically a trite morality play about a poor boy getting one over on his rich father-in-law (the song seemed to be about committing real estate fraud, but never mind), Frizzell's take is infectious. Despite some potential tongue-twisting groaners (how many ways can you rhyme Saginaw, Michigan?), Frizzell's version feels effortless.

And that was just about it. In 1965, he had a minor hit with Harlan Howard's "She's Gone, Gone, Gone." After that came a string of indifferently received albums.

Would things have worked out the same way for Williams if he hadn't died as he did, when he did, on the first day of 1953? He's a giant now, but how much of that is due to the legend? He was a better songwriter than Frizzell, but back in the day it was too close to call. When they played shows together, they flipped a coin to decide who would go on first.

It's rumored they secretly traded songs -- Hank wrote one and gave it to Lefty, who recorded it and claimed the publishing. Hank did one of Lefty's. They both charted high. Nobody ever figured out who wrote what.

But Hank was at least as problematic to work with as Lefty, and think about what happened in the middle of the '50s with that boy out of Memphis. When Sam Phillips, Elvis Presley and the rest of them set the world on fire. Hank might have had some fallow years too.

Then came that countrypolitan thing. When honky-tonk came back a little bit, Frizzell's protege Haggard was doing it just as well, maybe better.

Maybe that's why you never heard of Lefty Frizzell.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

RELATED ARTICLE

https://www.arkansa…">Frizzell dominated country music in '50s

Style on 12/09/2018