Neville Chamberlain is popularly viewed as a weak, if not foolish leader; even ahistorical Americans associate his name with policies of appeasement and concession.

His image -- wing collar and furled umbrella -- is summoned whenever the words "upper class twit" are sounded. His name still comes up in letters to the editor and vitriolic social media posts, serving as a kind of all-purpose term of obliteration for the gung-ho and hawkish. He is generally seen as the antithesis of his successor as British prime minister, the bulldoggish Winston Churchill.

It is not as simple as we make it. But Chamberlain was -- along with Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and French premier Edouard Daladier -- a signatory of the Munich Agreement which, on Sept. 30, 1938, virtually handed over Czechoslovakia to Hitler in the name of "peace in our time."

Actually, the agreement was only supposed to give to Hitler the Sudentenland, the industrial Czechoslovakian border region where 3 million ethnic Germans lived. But it also handed over to the Nazi war machine 66 percent of Czechoslovakia's coal, along with 70 percent of its iron and steel. Over the next year, Hitler terrorized the Czech government into essentially ceding the western provinces of Bohemia and Moravia and ultimately Slovakia and the Carpathian Ukraine to Germany.

In each of these German "protectorates," Hitler set up pro-Nazi puppet regimes. By the time of the invasion of Poland in September 1939, Czechoslovakia had for all practical purposes ceased to exist.

Chamberlain, who met privately with the Fuhrer at his mountaintop retreat Berchtesgaden before the Munich conference, was convinced Hitler was a rational actor (if not a gentleman, as has often been reported) and that his territorial demands were not unreasonable.

"I cannot believe that you will take the responsibility of starting a world war, which may end civilization, for the sake of a few days' delay in settling this long-standing problem," he wrote to Hitler on Sept. 27, 1938, pledging that the British and French would keep the understandably recalcitrant Czech government in line.

After the Blitzkrieg, when it became clear Hitler never had any intention of abiding by the agreement, Chamberlain was embarrassed; his credibility destroyed. As the Nazis occupied Norway and Denmark, he was finished as a credible leader. On May 7, 1940, Leo Armey, a Conservative member of Parliament, addressed Chamberlain by paraphrasing Oliver Cromwell's words to Parliament in 1653: "You have sat too long for any good you have been doing lately. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!"

Churchill, a problematic and vainglorious figure in his own right, stepped in to become (in the eyes of a 2002 BBC poll at least) "the greatest Briton of all time," the man of England's "finest hour."

But ...

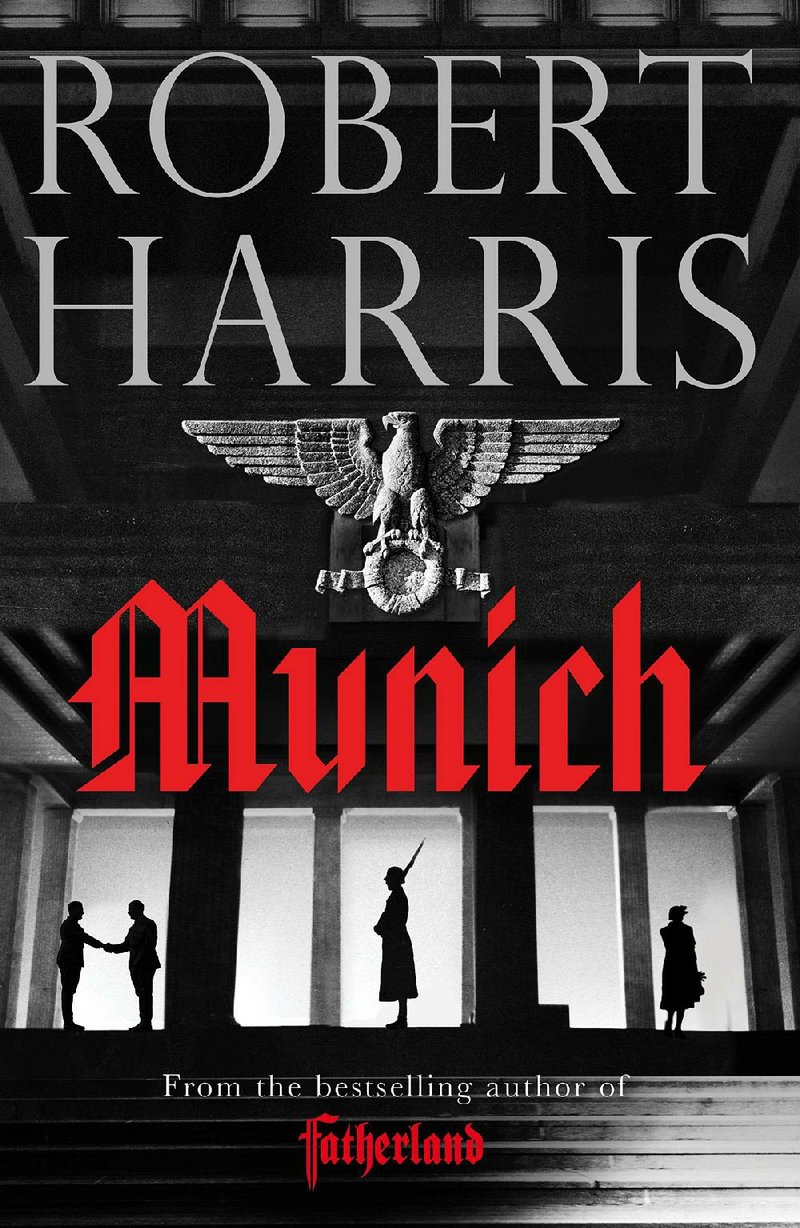

As writer Robert Harris points out in his lucid and engaging new novel Munich (Knopf, $27.95), without the Munich agreement Hitler would have immediately sent troops into Czechoslovakia, and France and Britain would have declared war. And England, especially, was not up to fighting a war in 1938. The memory of the nearly 750,000 men lost barely 20 years before was still fresh. The Royal Air Force had only 20 operational Spitfire fighters and the German Luftwaffe had proved its effectiveness in the Spanish Civil War. They might have bombed a defenseless Britain into submission in weeks.

Hitler did not want to wait a year to begin his glorious campaign. Chamberlain forced him to. Harris speculates that Chamberlain got the better of Hitler at Munich by delaying what turned out to be inevitable. (Though at the time, no one could see the future. There were at least five attempts on Hitler's life between the signing of the Munich agreement and the entry of the British and French into the war.)

It is somewhat ironic that the chief strength of Munich is Harris' recounting and contextualizing known facts -- Munich is more persuasive as an evocation of fraught times than it is a thriller. He focuses his story through the twin lenses of two relatively minor players, a low-level German Foreign Office staff member named Paul von Hartmann and a British aide to Chamberlain named Hugh Legat. They knew each other at Oxford years ago, and now both see the world plunging toward the abyss. They are good men, not great men, and they are powerless before the rising tide of fascism.

So long as survey classes are the rule, Munich won't rehabilitate Neville Chamberlain's reputation. But it does present the reader with a nuanced view of a problematic figure, one who agreed with his storied successor that "meeting jaw to jaw is better than war."

Harris makes the case it wasn't Chamberlain who was hopeless; it was the world itself.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 02/04/2018