That Albert Murray is not as well-known as James Baldwin or Norman Mailer is more a (mis)function of the American celebrity machine than any discernible daylight between the quality of these public intellectuals' thought or work; what Mailer and Baldwin could be and Murray never was is reducible to caricature.

A scholar, critic and novelist who had a parallel career in the military, Murray was a remarkable man. A product of Tuskegee Institute, he returned to the school to teach literature after a stint in the U.S. Army Air Corps, only to be called back to active duty during the Korean War. He seemed to know every major figure in black culture. His friend Ralph Ellison was a older student at Tuskegee when Murray was an undergrad; they checked out many of the same books from the library.

In 1957, after a mild heart attack allowed him to take early retirement from the military, Murray moved to Harlem, to an eighth-floor corner apartment at 461 Lenox Avenue with a spectacular view that inspired Romare Bearden's six-panel tribute to the neighborhood, the mural-size collage The Block (1971). Murray lived there until his death at the age of 97 in 2013.

It took him until 1970 to publish his first book, the uneven but essential essay collection The Omni-Americans. It was written partially in response to Daniel Patrick Moynihan's The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, a 1965 study Moynihan undertook on his own initiative when employed in Lyndon Johnson's Department of Labor. The future New York senator concluded that the black family was in crisis, and that the "matriarchal structure of black culture" emasculated black men, resulting in a "tangle of pathology ... capable of perpetuating itself without assistance from the white world."

Murray objected to the paternalism of the "Moynihan report" and the vulgar literalism of the social science it employed.

"Nowhere does Moynihan explain what is innately detrimental about matriarchies," he wrote. "... Harlem Negroes do not act like the culturally deprived people of the statistical surveys but like cosmopolites. Many may be indigent but few are square. They walk and even stand like people who are elegance-oriented ... They dress like people who like high fashion and like to be surrounded by fine architecture."

But he also pushed back against the separatism of the Black Power movement, denouncing both the "folklore of white supremacy" and the "fakelore of black pathology."

"The United States is in actuality not a nation of black people and white people," Murray wrote. "It is a nation of multicolored people ... Any fool can see that the white people are not really white, and that black people are not black. They are all interrelated one way or another ... American culture, even in its most rigidly segregated precincts, is patently and irrevocably composite. It is, regardless of all the hysterical protestations of those who would have it otherwise, incontestably mulatto."

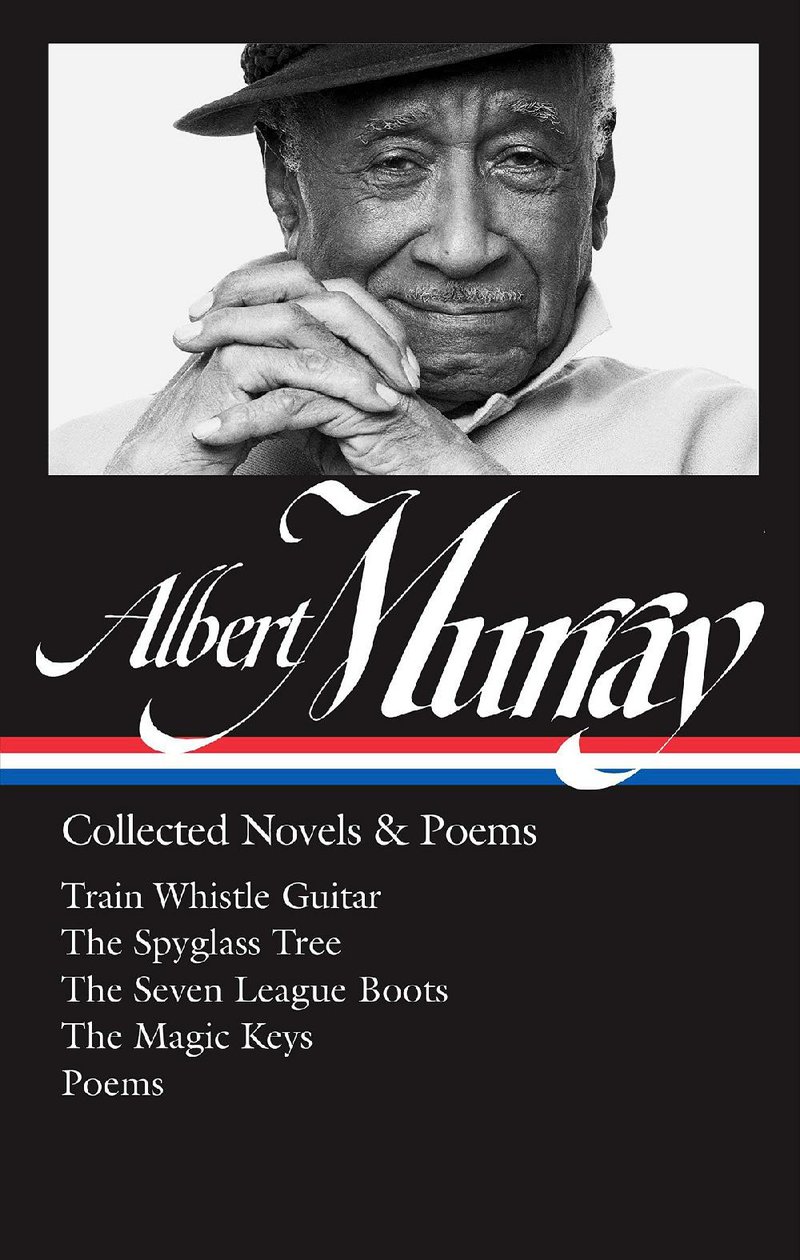

In 2016, the Library of America published a volume of Murray's memoirs and essays, following it last week with Murray's Collected Novels & Poems, a volume that is an absolute joy to read. Murray's freewheeling jazz and blues-infused style belies the careful precision of his fiction. He began work on the autobiographical story "Jack the Bear" in 1951 but didn't publish the first part of it until 1974 as the novel Train Whistle Guitar. The second part, The Spyglass Tree, didn't appear until 1991.

If you can have only one volume of Murray's work, go with the nonfiction. But this one is more fun.

. . .

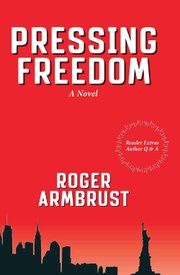

Former journalist Roger Armbrust is a poet of some accomplishment, a sonneteer working with modern themes. His 2009 collection The Aesthetic Astronaut is a remarkable combination of chops and heart. But it's still poetry, which means a limited audience.

His new book Pressing Freedom (Parkhurst Brothers, $22.95) is an audacious novel with narrative points ripped from the headlines (and a narcissistic president with orange hair) and a protagonist -- a Vietnam veteran turned newspaper reporter named Reeves Franklin -- who comes across as an aging Jack Reacher, damaged and physically competent and living by his own code. Which is to say that while the mode of the book is sometimes as groaningly overt as the sort of Hollywood action movie it aspires to be, it is good fun -- especially for Arkansas residents who will be quick to recognize many of the scarcely described place names.

But what really gives the book its kick is that Franklin writes sonnets -- some of which are nearly as good as Roger Armbrust's.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 02/18/2018