BENTONVILLE -- "Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus, the Proust of the Papuans?" Saul Bellow once infamously asked an interviewer who may have been probing the great man for his views on multiculturalism, an incident that produced a minor firestorm -- although the writer alleged in The New York Times it was the result of a misunderstanding on the interviewer's part.

What Bellow was speaking to was "the distinction between literate and pre-literate societies." He was no "racist," he was not even "insensitive." And besides, his critics were all Marxists.

“Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983”

When: Through April 23

Where: Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 600 Museum Way, Bentonville

Admission: $10 for the exhibition, free for members and ages 18 and younger; museum admission is free

Hours: 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday, 11 a.m.-9 p.m Wednesday-Friday, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturday-Sunday. Closed Tuesday

Information: (479) 418-5700, crystalbridges.org

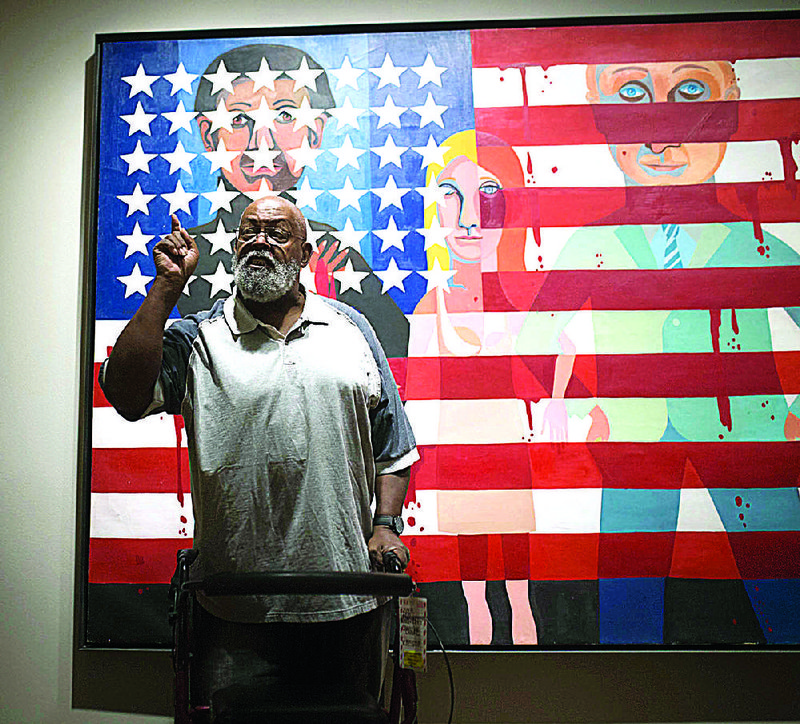

Dana C. Chandler Jr. is reminded of Bellow's words as he steers a rolling walker he seems not to need through the galleries of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. While he allows that the museum's current exhibition, "Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983," is "one of the most important shows of the century," one gets the sense he doesn't view it quite as vindication.

"We knew that we were as valid and that our work was as significant as anything done in the world," the artist and teacher -- he taught at Boston's Simmons College from 1970 until retiring with emeritus status in 2004 -- says. "We didn't really care that the critics at that time were not able to be grown enough to be able to deal with it. You can see that the work that we do is as good as any work that is done in the world. Even back in that time, when we didn't have access to galleries and museums and other things and we would have curators say things to us like 'What black art?' Because they didn't understand what they were looking at -- because at that time the curators were white and weren't interested in understanding what they were looking at. Now that's changing with this new generation of people -- not just black people -- whose minds are open, where the minds at that time were not open at all."

Not that Chandler -- also known as Akin Duro -- was completely overlooked back in the day. A writer for the Harvard Crimson, Caldwell Titcomb (who'd go on to be president of the Boston Theater Critics Association and professor emeritus of theater criticism at Brandeis) visited him in 1967 for a piece on Chandler's one-man show "Black Power Revolution in Art," held in Chandler's hometown of Roxbury, Mass.

Titcomb called him "one of [the Boston] area's most forceful artistic spirits."

"Chandler, an ardent Black Power advocate, is a man with fire in his belly; but he chooses to channel it into art rather than arson," Titcomb wrote. "... He is stocky, has a handsome bearded face, and chooses to wear a symbolic slave bracelet. He is extraordinarily articulate verbally, and by funneling his anger into his art, can afford to be genuinely warm and personable in face-to-face dealings with whites. There is, thus, a division in his work between violence and restraint, and a division in himself between anger and cordiality."

These days, we might be amused or wince by what comes across as Titcomb's patronizing position; but it is important to understand that the '60s were a different world and to note that the description of the artist feels apt more than 50 years later. There is a fierceness banked in Chandler; and what Titcomb identified as a "schizoid sort of position" informs practically every work in "Soul of a Nation," a brilliant show that's as valuable for its historicalization of black artists as it is for the presentation of work that retains an incendiary thrill.

Titcomb was writing about Chandler before Fred Hampton, the 21-year-old chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, and deputy chairman of the national party, was shot and killed while in his bed during a pre-dawn raid by Chicago police and FBI agents executing a search warrant on Hampton's apartment, which served as a Black Panther stronghold.

Police claimed they were fired on by Panthers during the raid, but a subsequent federal investigation indicated the Panthers had fired but a single shot while law enforcement agents -- 13 of whom were indicted and later acquitted for the raid -- fired between 82 and 99 shots.

To support the police claims, misleading images of various door jambs in the apartment were distributed to the media -- what were said to be bullet holes suggesting the Panthers fired on police were actually nail heads. (Hampton's mother, along with the mother of Mike Clark, another Black Panther leader killed in the raid, sued the federal government, state of Illinois and city of Chicago for violating the civil rights of their sons. The suit was settled in 1982 with the government agreeing to pay the women $1.85 million.)

Chandler, who counted Stokely Carmichael and other Black Power leaders among his friends, responded to Hampton's killing by painting a trompe l'oeil acrylic depicting a section of Hampton's bullet-riddled bedroom door, with a blue and white sticker featuring a star and the words "U.S. Government Approved 1969" above a nameplate reading "Fred Hamton [sic], Black Panther Party."

That painting was stolen from a group show in the early '70s and never recovered, but photographs of it reveal a straightforward, almost tombstone-like memorial. Chandler decided to remake it soon after it disappeared, this time using an actual door he splintered with bullets and painted in the red, black and green of the Pan-African flag. Chandler again included the sticker, modified this time to show four stars, and the nameplate, this time with Hampton's name spelled correctly.

While it's impossible to evaluate a lost work, Fred Hampton's Door 2 (1975) registers as a defiant yet eloquent protest in the tradition of Emmett Till's mother insisting on an open casket for her murdered and disfigured son. Chandler lets the artifact bear witness to the ugly reality of state power brought to bear against the individual; bullets came through the door first.

When Chandler says black artists don't need the acceptance of the art world to be vindicated, he's being serious. The future will discover lots of Fred Hampton's doors. But he's also pragmatic when he urges collectors to buy his work as well as the work of other black artists who, after all, face the same sort of financial demands as everyone else.

And he's not joking when, during a question and answer period with journalists at the end of the walk-through, he loudly offers his phone number to anyone who wants to call him and hear his story directly from the source. You get the feeling this is a man who's weary of having other people speak for him.

. . .

"Soul of a Nation" was organized by the Tate Modern in London in collaboration with Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and Brooklyn Museum, New York. It will be at Crystal Bridges through April 23 (before moving to the Brooklyn Museum in September).

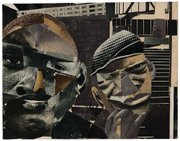

The exhibition features 164 works by 60 American artists (there were a few more at the Tate) who directly addressed American racial problems during the Civil Rights era and beyond. It begins roughly about the time of the 1963 March on Washington, with the formation -- by Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, Charles Alston and Hale Woodruff -- of the Spiral group in New York, a collective of black artists intent on exploring the relationship of art to activism, particularly the problems facing black artists in a segregated American society.

For instance, was it legitimate for a black artist to make art for art's sake, or was there a moral obligation to produce work that served the struggle? Was abstract art a legitimate way of addressing a black audience? Was there even such a thing as a black aesthetic?

While each member of the collective had answers for these questions, they did agree to limit their palette to black and white for their single group show in 1965. Lewis' semi-abstract painting America the Beautiful dates from before the formation of Spiral (it's dated 1960). The large (127-inch-by-163-inch) white on black oil (on loan from filmmaker Spike Lee and his wife) reads as a nighttime array of robed figures, in context clearly Ku Klux Klan members carrying crosses and torches.

Yet Lewis, who studied alongside Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell and who had been painting in an Abstract Expressionist mode for more than 20 years by the time of the Spiral show, was insistent that "aesthetic ideas," rather than political concerns, had primacy in his work.

"I am not interested in an illustrative statement that merely mirrors some of the social conditions, but in my work I am for something of deeper artistic and philosophic content," Lewis told Jeanne Siegel of ArtNews in 1966. He is no polemicist; while his early figurative paintings (from the 1930s) often depicted social conflict and topical themes (breadlines, police brutality), by the 1960s he was more concerned with pure painting.

Ironically, as the only black artist among the first generation of Abstract Expressionists, his work was often overlooked by black and white dealers and gallery owners during his lifetime.

. . .

If anything, the scope of the show -- co-curated by the Tate's Zoe Whitley and Mark Godfrey -- is overwhelming, and it might be better experienced in smaller chunks than a day-tripper to Bentonville might be able to give it.

The photography component is exceptionally strong and might have broken off into a number of worthwhile shows. Pioneering black and white photographer Roy DeCarava, who did much to uncouple his art from expectations of evidentiary literalness and make it an expressionist tool, is especially well represented; and Lorraine O'Grady's wonderful series of conceptual photographs, "Art Is ..." from 1983, which turns up near the end of the exhibit, is worthy of a book-length treatment.

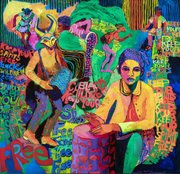

You could have mounted a fine exhibition just from the explicitly revolutionary materials that appear in "Soul of a Nation" -- such as Black Panther Party's minister of culture Emory Douglas' posters and illustrations from The Black Panther newspaper; Chicago collective AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) member Wadsworth Jarrell's candy-colored, textually explicit Revolutionary, 1972, and Faith Ringgold's Guernica-evoking painting American People Series #20: Die (1967).

Or you could focus on the marvelous humanism and wit of post-modern photo-realist Barkley Hendricks, a giant who died in April 2017 and who is represented here with three major works, Icon for My Man Superman (Superman never saved any black people -- Bobby Seale), a self-portrait from 1969; the technically precise What's Going On (1974) that adorns the cover of the exhibit's catalog; and Brilliantly Endowed (Self-Portrait) from 1977 that plays off a certain well-circulated myth about black men.

Hendricks is a fabulously talented painter, perfect in an almost commercial-arty way but always able to imbue his subjects with a wry twinkle of humanity that removes them from the realm of symbols and allows them a dignity beyond politics. He is able to convey a sense of his subject's genuine personality -- to arrange his pigments in such a way as to suggest a full-blown soul.

At the other end of the spectrum lies the abstractions of Sam Gilliam, William T. Williams and Jack Whitten, and Betye Saar's Rainbow Mojo, 1972, a cosmic acrylic on leather assemblage which suggests a certain syncretism of new age, pagan and voudon traditions. (Saar's acerbic and funny 1972 assemblage Her Liberation of Aunt Jemima -- which presents the pancake deity in a shrine-like box with a broom and shotgun and a black power fist ascendant -- also makes an appearance.)

So rich is the exhibit that even people who have spent a lot of time wandering through galleries are likely to encounter the unexpected. I did that with Timothy Washington's One Nation Under God (1970), a remarkably powerful etching on aluminum that reminds us of the broken promises made by the U.S. government to former slaves.

Most of the artists represented in these galleries are gone now. Few of them died wealthy. But Chandler and his remaining cohort acknowledge that any artist who can afford the cost of materials probably should count themselves fortunate. Chandler says he didn't expect to be recognized during his lifetime; he knows he's lucky to be included in a show like this, and that sometimes it has nothing to do with the quality of the work produced.

He knows of a lot of lost Tolstoys.

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 02/18/2018