Arkansas public officials don’t know for sure how many of the state’s residents are dying because of opioid painkillers and other drugs but are working to change that, several said in recent weeks.

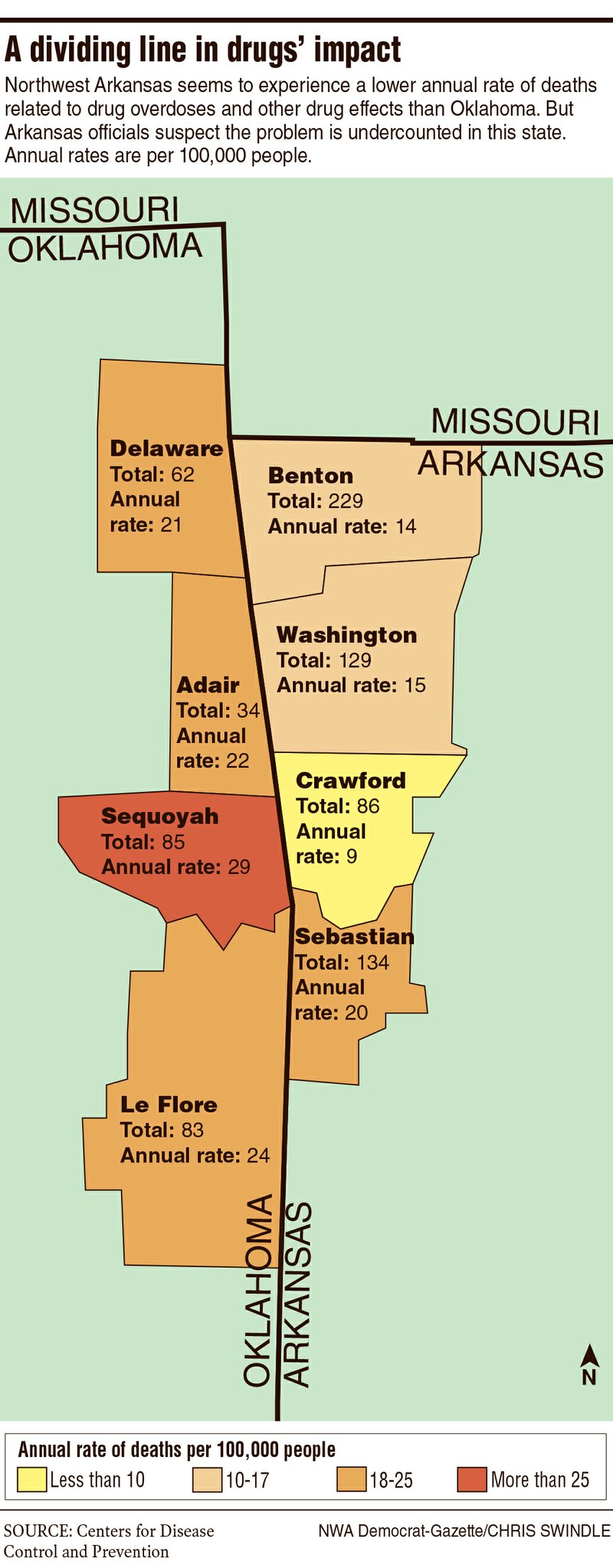

Federal data on drug-induced deaths, which can come from overdoses or longer-term effects of a substance, at first seem to make Arkansas look good compared with neighbors such as Oklahoma. The rate of those known deaths adjusted for population was half as high in Northwest Arkansas in 2016 as it was just over the Oklahoma border.

Other numbers suggest reality is more complicated than that comparison. Benton, Crawford, Sebastian and Washington counties have a lower rate of drug deaths than their Oklahoma neighbors but lost more people because their population is so much bigger, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The agency counted almost 600 drug deaths in the four counties from 2010 to 2016, more than twice those on the other side of the border.

Arkansas as a state has the second-highest opioid prescription rate in the country, behind Alabama and about 17 percent more than Oklahoma’s. Legal and illegal opioids account for a majority of all drug deaths in Arkansas and the rest of the country based on state and CDC figures.

Arkansas Drug Director Kirk Lane, who oversees substance abuse programs at the Department of Human Services, several coroners and a Department of Health spokeswoman all agreed Arkansas is likely missing or miscounting drug deaths. They and other experts point to several factors, including differences among coroners’ practices and resources and the fact people who die from drugs often are using more than one kind.

Roger Morris, Washington County coroner, said all opioid-related deaths he could think of also featured alcohol or other drugs. His Benton County counterpart, Daniel Oxford, said he sees other drugs as often as any opioids, sometimes mixed with alcohol.

Lane guessed Arkansas’ drug-related deaths could be twice as high as measured. For the state overall that would mean more than 2,000 deaths between 2010 and 2016 had drugs as a cause.

“Not having good data kind of skews the whole process of trying to solve the problem,” Lane said.

The Arkansas Department of Health and the nonprofit Arkansas Coroner’s Association are connecting every coroner in the state to an online, standardized reporting system to get better data, said Kevin Cleghorn, Saline County coroner and president of the association. The system is called MDILog and is marketed as a secure platform for death investigations.

Cleghorn said MDILog would let coroners document deaths the same way and share information with the State Crime Lab, which runs toxicology tests to see if a deceased person was intoxicated. If substances were involved, the system prompts the coroner to fill in more detail.

Health Department spokeswoman Meg Mirivel said a CDC grant of more than $200,000 is helping with the data improvement effort.

Cleghorn said the system would be far better than each coroner choosing a different way to track deaths. Some counties haven’t kept death records of any kind, he said. Others rely on part-time coroners. Morris and Oxford said they request toxicology reports for all unnatural deaths and are confident in their counties’ data, but they know others don’t do the same.

“They’re wanting to do it right, they just don’t have the financial means to do it right,” Cleghorn said. He and Lane agreed states throughout the country are struggling with similar issues on tallying the impact of drugs.

The system will be free for counties to use and should begin rolling out to some this month.

In the meantime, Arkansas and Oklahoma are tackling the role of opioids in residents’ deaths in similar ways. The two states have prescription monitoring programs to make it easier to detect when people get several opioid prescriptions in quick succession. Lane and others in both states said increased grants from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health are going toward more addiction treatment.

The states, the Cherokee Nation in eastern Oklahoma and Arkansas’ groups for cities and counties are joining a lawsuit against opioid manufacturers, claiming wrongdoing in their marketing and selling of their potentially addictive medications.

“Federal law mandates that they have reasonable safeguards in place to ensure any area’s not flooded with pills like we have been,” said John Young, Cherokee assistant attorney general. The national lawsuit includes Walmart and Walgreens as defendants and claims hundreds in the nation have died because of opioid sales in recent years.

Defendants have largely said they’re committed to solving the opioid problem and called lawsuits such as these unhelpful. The Healthcare Distribution Alliance, which represents some of the pharmaceutical companies being sued, said in a statement in December the opioid problem stems from several factors, such as U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration approval for increased opioid production.

“Distributors respond to demand in the market for medicines — they don’t create it,” the group said. “Expecting distributors to have unilaterally stemmed the flow of opioids — a flow that increased yearly with the explicit oversight and approval of the DEA — is a transparent attempt by former DEA officials to shift the blame for their own failed approach to regulation during the growth and peak of the epidemic.”

Dan Holtmeyer can be reached at dholtmeyer@nwadg.com and on Twitter @NWADanH.