Do some searching online, and you’ll learn that 233 fish species swim in Arkansas waters. You’re no doubt familiar with many. Almost everyone can identify my favorites, the catfish, for example. And most people would have little trouble naming species such as the largemouth bass, bluegill, crappie, striped bass, various kinds of trout and even unusual giants like the alligator gar and paddlefish.

There is one group of Arkansas fish you may know very little about, however, despite the fact that some members of the family may reach weights near or exceeding 100 pounds. Sturgeons are scarce here, and most Arkansans are unfamiliar with these interesting creatures.

Fossil records indicate that sturgeons swam in a world swarming with dinosaurs 200 million years ago. The 25 living species of sturgeons range widely throughout North America, Europe and Asia. Seven species occur on our home continent, and three of those — the shovelnose sturgeon, lake sturgeon and pallid sturgeon — occasionally turn up in Arkansas waters.

Shovelnose sturgeons are sometimes caught on hook and line by anglers bottom-fishing for catfish or other species. But lake sturgeons and pallid sturgeons are so rare in Natural State waters, most fishermen have never seen or heard of one.

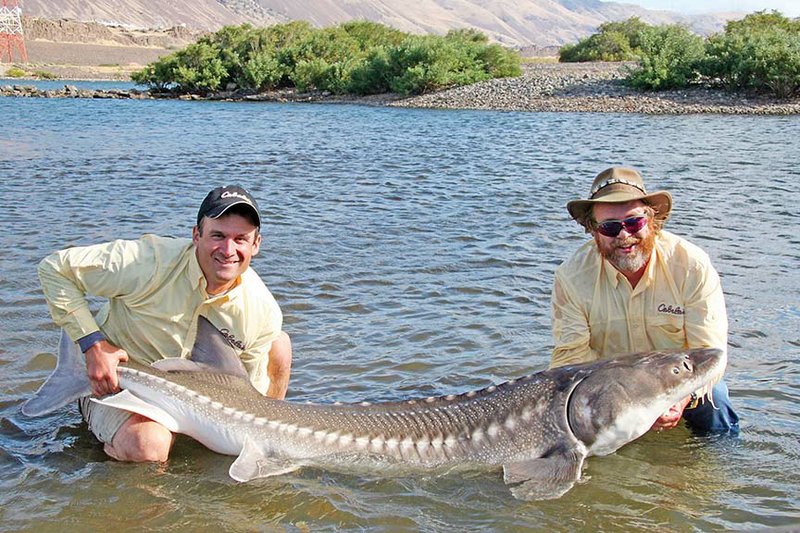

Sturgeons look quite odd. Their bodies are not covered with small scales like a bass or the smooth skin of a catfish. Instead, they wear a complete suit of protective armor that comprises bony segments called scutes. Each scute is topped with a sharp spur, which can injure anyone who handles a sturgeon carelessly.

While sturgeons aren’t likely to be mistaken for sharks, they resemble those saltwater fish in having “heterocercal” tails (the upper lobe is longer than the lower). The sturgeon’s most recognizable features, though, are its big snout, retractable vacuum-cleaner mouth and a Hitler’s mustache of barbels (“whiskers”) dangling from its upper lip.

Some sturgeons rank among freshwater’s true giants. The white sturgeon of Pacific coastal rivers, for example, can weigh nearly a ton. Arkansas sturgeons are much smaller.

In the 1800s, these curious fish were important in the Mississippi River Valley. At that time, sturgeons were in high demand for their eggs, which produce high-quality caviar. Their flesh, delicious when smoked, was considered a delicacy, too.

Commercial fishermen also collected sturgeon swim bladders. These were made into isinglass, a transparent gelatin used in the manufacture of glue, wine/beer clarifiers and jelling agents.

Sturgeons are slow to grow and mature, requiring six to 25 years to reach spawning age. This makes them very open to overharvest. As a result, by 1900, commercial sturgeon fisheries throughout the fishes’ range had sharply declined as a result of a scarcity of the fish.

When the harvest of sturgeons decreased, some species might have returned to their former abundance, but environmental changes prevented a comeback. River channelization, dam construction and pollution destroyed the sturgeons’ essential habitat. Dams blocked migration from feeding grounds to upstream spawning grounds.

Today, no American sturgeons are abundant, and several species are on state or federal lists as threatened, endangered or species of special concern. Recreational and commercial fishing for less-rare sturgeon species are still allowed in many areas, but harvest regulations are usually strict.

In 1990, the pallid sturgeon was added to the federal endangered-species list. Little is known about this fish because it is rarely observed and infrequently taken on hook and line. Even historical records of the species are obscure because it was not formally distinguished from the shovelnose sturgeon until 1905.

In Fishes of Arkansas, authors Henry Robison and Thomas Buchanan note, “Only two records are known for Arkansas, one from the Mississippi River and one from the St. Francis River.” They note that the pallid sturgeon “is apparently rare throughout its entire range” and “may be threatened by man-made modification of the channel of the Mississippi River.”

The shovelnose sturgeon, the pallid’s lookalike cousin, is still common in big rivers like the Black, White, Red and Mississippi. Robison and Buchanan report, “In the early 1980s its population in the White River near Augusta was large enough to support the establishment of a modest sturgeon roe fishery. From 1980 to 1985, an average of 31,983 pounds of sturgeon per year was taken commercially in Arkansas.” The shovelnose is our smallest sturgeon, rarely exceeding 5 pounds. The pallid, by comparison, may weigh more than 65 pounds.

The lake sturgeon reaches the southern limit of its range in Arkansas and is very rare here. Of the five records known for the state, one came from the Little Missouri River, two from the Mississippi River and two from the lower White River. Lake sturgeons are extremely long-lived, occasionally reaching 120 to 150 years and weighing up to 300 pounds.

All Arkansas sturgeons share a preference for strong currents over sandy or gravel bottom in large rivers. They feed on the bottom using their barbels to find foods such as mollusks, worms, insects, crustaceans and small fish. Arkansas anglers often call them hacklebacks or duck-billed catfish.

The pallid sturgeon is protected by federal law, and fishermen should be aware that possession of the fish or any of its parts is prohibited. Pallids and shovelnoses are similar in appearance, but the pallid is usually grayish-white with a smooth belly. Adult shovelnose sturgeons are typically tan, and the belly is covered with bony plates.

Also, the pallid’s four barbels are staggered, with the two short center barbels are positioned slightly closer to the front of the snout than those of the shovelnose, whose barbels are about equal in length and set in a straight line. Anyone who catches a sturgeon that cannot be identified should release it immediately.

Arkansas’ shovelnose-sturgeon population appears healthy, but Steve Filipek, who conducted fisheries research for the Game and Fish Commission for decades before retiring, said appearances can be deceiving.

“We know that loss of habitat in our big-river ecosystems is having a detrimental effect on sturgeons and other big-river fish,” he said. “In the case of sturgeons, though, we don’t know how severe the problems are because little research has been done in Arkansas.”

Certainly, much remains to be learned about these ancient fish. Unfortunately, sturgeon populations are still threatened by the continuing degradation of our big-river ecosystems. Unless we react quickly to protect these amazing creatures, we may never know all the fascinating secrets they could share.