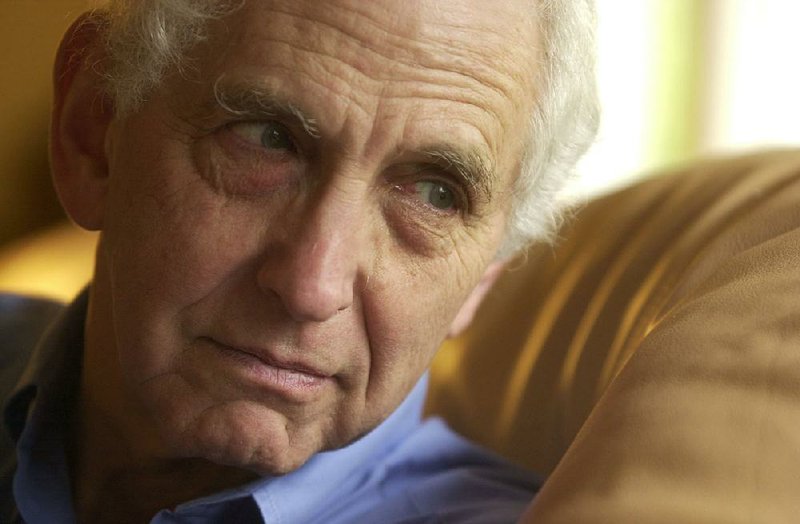

In 1971, Henry Kissinger dubbed Daniel Ellsberg "the most dangerous man in America" after the latter leaked a 7,000 page study called "The Pentagon Papers" to The New York Times, The Washington Post and other news organizations.

President Lyndon Johnson's Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara commissioned the history, which revealed that four presidents (Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson) misrepresented America's role in Vietnam and chances of meaningful victory were unlikely.

Ellsberg, who was one of the authors of the study, shamed politicians, bureaucrats and other insiders such as Kissinger in the process and risked spending the rest of his life in prison. Instead, the Nixon administration's dirty tricks (which included breaking into the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist) backfired, and he and co-defendant Anthony Rizzo walked free because the judge declared a mistrial.

"Over 40 years, I've been asked dozens of times, 'What gave you the right or what made you think you had the right to put this information out?" I've virtually never gotten the question, 'Why did you have the right to keep it secret earlier?' It doesn't occur to people," he says from San Francisco.

Ellsberg's personal struggle is sketched out in the first few minutes of Steven Spielberg's new movie The Post, which focuses primarily on the risks that publisher Katherine Graham (Meryl Streep) and executive editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks) took in publishing the information Ellsberg leaked.

Emmy-nominated Welshman Matthew Rhys (The Americans) plays Ellsberg, which leads him to admit, "It's very nice to be portrayed by a terrific actor, Matthew Rhys, who happens to look a lot like the way I did at the time, only better. That's gratifying."

In fact, the early portions of the film mirror portions of Ellsberg's 2003 memoir Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. An exchange on a jetliner in the mid-'60s with McNamara, where the secretary candidly admits the war is going badly, only to lie about it later, is taken almost word-for-word from Ellsberg's account.

The film also shows that Ellsberg, a civilian at the time (he was discharged from the Marine Corps as a first lieutenant in 1957), following ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) and American troops in uniform. He recalls, "You just didn't wear slacks in a rice paddy, you know. I was wearing jungle boots and combat field gear that I'd picked up here and there gradually. What I didn't have ... was a helmet, and since I went out on many field patrols, day and night for a few weeks in 1967 I had to borrow a helmet. [Spielberg] has my character borrowing a helmet when he goes out on patrol ... I had to turn it back to them when I got done. It wasn't what I wore in town."

KUBRICK'S LAST LAUGH

If The Post owes a debt to Secrets, Ellsberg's sobering new book, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner, is ironically tied to Stanley Kubrick's disturbing 1964 comedy Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. The book gets more than its title, which refers to the movie's main weapon, from the film.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Ellsberg worked as a military consultant for the RAND ("Research And Development") Corporation and observed that, contrary to what we've been told about the president and his "nuclear football," determining the authority to launch a nuclear strike was a messy business.

In The Doomsday Machine, he recounts how some bases in the Pacific had fitful communications with Washington, and it was hard to tell when and if a strike would be launched and who might do it. People like the movie's crazy Gen. Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) could have sent missiles to their Soviet targets.

Kubrick consulted with fellow RAND researcher Herman Kahn, and according to Ellsberg, it shows.

"It was a documentary," Ellsberg says. "Dr. Strangelove deserves to be seen again and again as a description of what the dangers actually are, not just what they were but what they are just now.

"I understand that in one of the articles on Dr. Strangelove that Herman asked for some compensation afterwards because they did, in fact, put some of his words in Dr. Strangelove's (Peter Sellers) mouth or in the mouth of (Gen.) Jack D. Ripper or (Gen.) Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott) or one of the various characters. Kubrick had to tell him, no, it doesn't work that way.

A STRIKE ON RUSSIA

Dr. Stangelove and The Doomsday Machine reveal that nuclear warfare can potentially harm both the people targeted in the strike and those who pull the trigger. During his research at RAND, Ellsberg discovered that a strike on Russia could have destroyed Finland and other neutral countries and our NATO allies.

"The fallout of nuclear attacks on North Korea would affect China and parts of Russia, I would say. Of course, a retaliation from the North Koreans to our attack would very, very likely affect South Korea. It would be almost foregone. It would also hit targets in Japan as well," he says.

"The effect of nuclear winter would be to stop all harvests for a decade. People would pretty much all starve to death within a year. I understand that the world's food supply for the whole population is about 60 days, and that's concentrated in a few countries like our own. So, we'd last longer, and others would go faster from an absence of food. If people hadn't stored up a decade's worth of food, they wouldn't survive."

In addition, maintaining nuclear arsenals is a dangerous business. The Doomsday Machine documents situations like the Cuban missile crisis where nuclear weapons could have been used. In addition, the footnotes list an incident in 1980 where a dropped wrench caused a Titan II missile near Damascus to explode without detonating the warhead. An airman died in the accident.

"Wasn't that a nine-megaton warhead (it ranged from nine to 10)? That would have been more than all the wars of human history in explosive power in that one weapon.

MovieStyle on 01/19/2018