Two death-row inmates spared from execution last year had their cases heard again Thursday by the Arkansas Supreme Court, where their lawyers argued the justices have been wrongly applying 30 years of case law.

Convicted murderers Don Davis and Bruce Earl Ward were to be executed April 17, but they were granted reprieves last year by the Arkansas justices, in part to wait and see what the U.S. Supreme Court decided in another case. An Alabama inmate sought the right to have an independent mental-health examiner testify on his behalf, at the state's expense.

The high court in Washington ruled for the Alabama inmate, and on Thursday, federal public defenders representing Ward and Davis said the Arkansas court should do the same.

Regardless of how the Arkansas justices decide, neither of the condemned men faces an execution date.

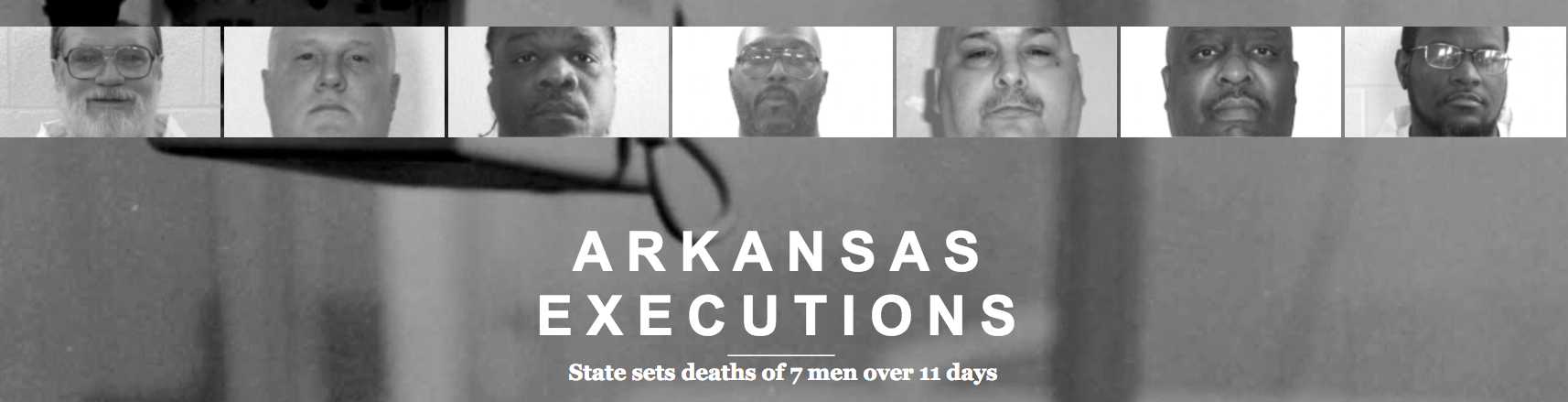

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

Ward, 61, still has other claims regarding his mental competency that have yet to be resolved by the courts. Davis, 55, does not, but one of his attorneys, Scott Braden, said Thursday that an unfavorable ruling is ripe for appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Unaffected by all the judicial deliberations and legal filings is the simple fact that one of the three drugs Arkansas uses in executions is set to expire March 1.

The back-and-forth Thursday between attorneys and justices in the circular Supreme Court room, however, was focused on the past -- specifically, the justices' own 2015 ruling that Ward was not entitled to an independent mental-health expert at his 1997 sentencing.

In that decision, the court upheld its long-running standard that an evaluation at the State Hospital in Little Rock fulfills a defendant's right to a "competent psychiatrist," under the U.S. Supreme Court's 1985 Ake v. Oklahoma decision.

The Arkansas Public Defender Commission began paying for indigent defendants to have their own psychiatrists in 1998, so Ward did not receive one at his trial held earlier. The justices in 2015 declined to overturn his sentence on that basis alone. Davis' defense team did have their own psychiatrist, but federal defenders said Thursday that the doctor's work was not sufficient.

"What precisely has changed since 2015?" Justice Rhonda Wood asked.

Braden, delivering his argument's in Ward's case, said he risked being facetious in his response to the question: "Everything and nothing."

The court has been interpreting Ake wrong all the way back to 1985, he said. Not only does the U.S. Supreme Court require a psychiatrist to be competent, he argued, but also they must be readily available to "assist in evaluation, preparation and presentation of the defense." State Hospital doctors, he argued, are too closely aligned with the prosecution.

But Solicitor General Lee Rudofsky of the state attorney general's office told the justices they have continued to correctly interpret the law. Changing course now, he said, "wouldn't just open up the floodgates, it would blow up the dam."

Other than Davis and Ward, there are 26 men on death row at Arkansas' Varner Unit.

Based on their line of questioning, the justices also appeared skeptical of Braden's arguments. Several wondered aloud if what the inmates were really seeking was the right to have a psychiatrist who will say whatever is in the defense's best interests.

"Is there a difference between being independent of the prosecution and being adverse to the prosecution?" Justice Shawn Womack asked.

Braden and his co-counsel, April Golden, said there is. An independent expert, they argued, would not just testify but also help defense attorneys build a legal strategy, explain mitigating factors during sentencing and prepare for the cross-examining of other witnesses, Golden said.

According to the attorneys, Ward has been diagnosed with schizophrenia while living in a single-man cell on death row. A history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may have played a factor in Davis' crimes, Golden told the court.

Both men were convicted of killing women more than a quarter century ago. Davis was found guilty of shooting 62-year-old Jane Daniel after robbing her inside her Rogers home in 1990. Ward was found guilty of killing 18-year-old Rebecca Doss in 1989 in the restroom of the Little Rock convenience store where she worked.

If the court rules in their favor, Ward will be eligible for a new sentencing, while Davis' case could go back to trial, Braden said.

Metro on 01/26/2018