Richard Yada's first impressions of the world were formed behind a barbed-wire fence where guards carried rifles on their shoulders.

Nearly 8,000 Japanese-Americans were taken from their homes during World War II and imprisoned in barracks in the Rohwer War Relocation Center for the duration of the war. Another camp in Jerome held about the same number.

Richard, who was born at Rohwer, his parents, his aunt and his brother, Bob, were held at the camp. The Yadas were the only family to stay in Arkansas after the war ended. The family would eventually build a successful greenhouse business after years of sharecropping.

Richard and Bob went on to graduate from college, and both served in the military for the same country that had once made them prisoners.

This is part one of a two-part series. http://www.arkansas…">Click here to find out what happened to the Yada family after internment.

Attempts to keep the memories of what happened at the camps from fading are ongoing in McGehee, a town near Rohwer and Jerome, and in Little Rock at the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, which started a two-year series of exhibitions about the camps in 2017. A new exhibit focused on student life opened earlier this month.

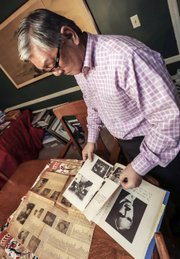

Richard, who was only in the camp for the first two years of his life, says most of his knowledge of what happened, and why, has been gathered through bits and pieces of information over the years.

"They never had an occasion to say, 'Let's sit down and talk about what happened in the camp,'" the Little Rock resident says of his parents. "We never did that."

The Arkansas camps were two out of 10 across the United States that held more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans during the war. Many were American citizens, and none were ever convicted of espionage or treason.

By Dec. 7, 1941 -- the date Japan bombed Pearl Harbor -- Richard's family had been in the United States for generations. They were scattered; some lived in Hawaii, some in California. Some were still in Japan.

In the weeks and days leading up to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, seemingly insignificant decisions shaped lives -- determining whether a teenager lived or died, displacing an entire family branch, leaving another nearly unscathed.

NISEI

At the time, second-generation Japanese-Americans referred to themselves as "nisei." They operated under values of honor and obedience to authority, learned from their parents. One common Japanese phrase used among the nisei and their parents was translated: "It can't be helped."

-- Time of Fear, a PBS documentary about Rohwer

Richard's mother, Haruye Masada-Yada, was a member of the nisei. Her father came to the United States from Japan. Her mother came later as a "picture bride," Haruye, who was born in the United States, said years later during an interview with a representative from the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

Haruye died in 2014 at age 99; the interview with the museum is the last remaining record of her story.

Her parents lived in California, although they sent their children back to Japan for school. It was hard for their kids to get a good education in the United States because the parents moved often, looking for seasonal work and traveling to keep up as different fruits ripened.

When she came back to the States as a teenager, Haruye barely spoke English but tried to attend high school.

"I went, about three years only," she said. "I was placed with small children, so I became very frustrated and resentful being in that situation."

Her father got sick with what seemed to be stomach cancer, and the family moved back to Japan briefly when Haruye was a teenager.

The decision to come back to the United States after a year of treatment was not an easy one -- her father was the oldest male in his family and was expected to stay and carry on the family name in his own country.

He said it was impossible to make a living in Japan, and he avoided going back after the treatment because he would have been pressured to stay, Haruye said.

"No matter what, need to go back to America," Haruye says in a transcript of the interview.

When she was 21, relatives arranged for her to marry Sam Yada, who was about 10 years older. They met twice before their wedding in 1936.

"My aunt kept telling me that he was a good person, a very kind person, a persevering and honest worker," she said. Six decades later, when she heard he had died just before his 86th birthday, Haruye would sprint up stairs to get to him because the elevator was too slow.

Their oldest son, Bob, was born in 1937, and doesn't remember much of his experience living in California outside of playing in the dirt while his mother worked in the celery fields. In between shifts at the field, she cooked for people living in the workers' commune. Customers could buy meals for 50 cents each.

Sam was a mechanic, and when news of the war broke, the couple talked about moving their small family somewhere safer -- maybe Nebraska -- but decided against it; the change would have been too much stress and cost too much. Besides, Haruye liked raising her children in a simple farm life.

'AGAINST ESPIONAGE AND AGAINST SABOTAGE'

"Pursuant to the provisions of Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34 this Headquarters, dated May 3, 1942, all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien will be evacuated ... "

-- Orders from the U.S. Army

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, investigations began. Japanese-American leaders were removed from their positions and put in war camps. Language schools closed. Business operations were seized.

Although the act itself didn't specify Japanese-Americans, they were targeted with much higher frequency than German-Americans or Italian-Americans because they "wore the faces of the enemy."

Families were confused -- why was the FBI investigating American citizens? What were they looking for? Haruye's response was to get rid of any evidence. She didn't want the government to know she had been educated in Japan.

They built a fire in the front yard and tossed in personal effects, photos and signs of their heritage, says Bob Yada, Richard's older brother.

"You didn't know what the consequences were if the FBI found it," he says. Bob is now retired and lives in Fort Smith.

Soon after, the relocations started. Japanese-Americans tried handing off their property to friends and neighbors. One man recounted in information from the World War II Japanese American Internment Museum in McGehee that his father tried to hand off the family dog to a friend for safekeeping until he returned.

The man accepted care of the pet and promptly shot it.

Most of these moves happened from the West Coast to middle America where any traitorous prisoners would have a harder time communicating with the Japanese government. However in Hawaii, where Japanese fighters dropped bombs, and about a third of the population was Japanese, most families remained free, according to information from the museum in McGehee.

Estimates at the time showed that Hawaii's economy would have collapsed if all the Japanese-Americans had been pulled out of the workforce. Very few were interned at a camp; Sam's family was not.

Before the war started, Sam's teenage sister, Sadami Hamamoto, had traveled from Hawaii to stay with the family. She planned to stay for a year, help out on the farm and then go back to finish school.

If she had stayed, she would have been able to graduate with her friends on the island.

Instead, she graduated on a racetrack at a prison camp.

She, along with her brother, sister-in-law and nephew, was rounded up and taken to horse stables in Stockton, Calif., while the barracks in Arkansas were being prepared for their arrival.

"They had built some temporary barracks, and we got to stay in the barracks, but some of them had to stay in the horse stalls," Bob says.

When the housing in Arkansas was ready, the Yada family was loaded onto a steam-engine train for the four-day trip. Each family was allotted one bench to sit and sleep on.

"There was a conductor and he was joking with me," Bob says. "I was scared to death to ride on the train but when we got to our destination in Rohwer, he gave me a piece of Dentyne chewing gum."

There were a few stops, all in the middle of the desert with armed guards standing watch.

"I remember the MPs had a formation around the area so we wouldn't escape," Bob says.

"I don't know where we would escape to."

IMPRISONED

Gaman: A Japanese term of Zen Buddhist origin that means "enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity."

The road into Rohwer was lined with long, black, wooden buildings filled with families trying to make sense of things.

A guard tower at the front of the camp overlooked the structures built on the low-lying farmland.

A pile of scrap wood was quickly snatched up to be made into furniture. Sam made boxes for his family to store clothes and a crib for the baby they were expecting -- Richard.

The internees flooding into Rohwer and Jerome made the small Delta towns the fifth and sixth largest cities in the state.

The Yadas, like the others held at the camp, lived in one room with a potbelly stove, a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling and three Army cots lining the walls. The space was about 15 by 20 feet, Richard says.

Adults were allowed to work -- for the lowest wage an Army private could make at the time, about $17 a month -- to buy trinkets and candy from the commissary.

Sam worked as a lumberjack and in the kitchens. Haruye learned to sew in an adult class while caring for her sons.

Families rarely ate together; children chose to eat in the dining hall with their friends, and usually only saw their parents at night. This caused families to fracture in ways that proved difficult to repair, former internees say in the PBS documentary.

Bob ate with his friends and spent the days playing with them. He was still too young for school, and there were no chores to do in the camp.

"We had blow-gun fights and would sling clay balls at each other," he says. "We would roll up the clay ball, put it on the end of the stick, and just sling it."

Each internee was given a name tag to wear; it was required when they left the confines of their barracks. Bob's said "Robert," which was not his birth name, but it stuck and he had his name changed from Bob to Robert when he became a teenager.

Richard was born in 1943, about a year after the camp opened. An Army ambulance transported Haruye to a military hospital in the camp.

It was hard to find ways to celebrate big life events and holidays in the camps, but Bob says his mother tried. For his fifth birthday, she cooked a meal for just the family and took his picture.

One year on Christmas Eve, he asked his father if Santa Claus could bring him a new bicycle. Sam told his son that a bicycle wouldn't fit down the chimney, but that he could ask for something else. Bob decided on a Boy Scout knife, which was waiting for him the next morning.

"That was one of my most pleasant memories of incarceration," Bob says. "I never asked him how he got it."

Bob went to school at the camp through the second grade, but Richard was not old enough. Most of his memories of being imprisoned are blurry -- sitting on the grass next to his mother, the soldiers with their rifles, watching older kids play in the creek.

He didn't learn to speak English until after his family left the camp.

"When we got out of the camp and moved to Scott, I figured everybody else speaks English, so I'd better pick that up myself," Richard says. "I just blocked it [Japanese] off, and I wish I had some knowledge of that. It left."

As the war wound down, internees were allowed to leave to work in the interior of the United States. Richard and Bob's aunt got a job as a nanny in Ohio and left before the rest of the family.

Before leaving the camp, adults were required to fill out a loyalty questionnaire. It was designed to divide the Japanese-Americans into "loyal" or "disloyal" categories. Those in the disloyal category would be required to go to a higher security camp, and yet many were labeled disloyal, which researchers say was likely a response to being imprisoned without cause or trial, according to the Densho Encyclopedia, which chronicles the story of the Japanese-Americans during WWII.

Question 27 asked if men would be willing to serve in the draft. Question 28 asked if individuals would forswear any allegiance to the Emperor of Japan.

Sam and Haruye didn't feel allegiance to either country and answered "no" to both. Several men interned at Rohwer and Jerome served in the war, fighting in Europe.

"We were placed in camps, and how could they ask us such questions, that's what he [Sam] said," Haruye told the museum interviewer.

The Yada family was one of the last to leave Rohwer, and one of few who didn't go far.

PART 2 » War and remembrance: Japanese-American family struggles with patriotism after Arkansas internment

Style on 01/28/2018