A dozen years ago I wrote about a four-volume biography of Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson, a 19th-century baseball player some believe is the most important figure ever -- bigger than Babe Ruth or Jackie Robinson. Anson was not only the game's first great hitter, but the man primarily responsible for the color line that existed in major league baseball until Robinson and Branch Rickey broke it.

Still, most readers might be forgiven for finding a four-volume biography of anyone -- much less a player from baseball's dead ball era -- exhausting. What I found remarkable about Howard W. Rosenberg's work was his combination of scrupulous scholarship with an almost eerie absence of authorial ego. Rosenberg's methods were refreshingly basic. He relied most heavily on contemporary newspaper accounts from which he quoted at length. While he occasionally expressed opinions, he was quick to offer documentary evidence both for and against his suppositions.

His style could be abrupt, but for the reader already interested in the subject Rosenberg could be revelatory. His judgments were nuanced. He pointed out that while Anson was certainly racist and on a number of occasions refused to take the field when other teams used black players, he was also a well-known hothead. His influence on teams other than his own has probably been overstated.

Rosenberg was alert to the connections between Anson and other figures such as Mike "King" Kelly (whose story was highlighted in the second volume, Cap Anson 2: The Theatrical and Kingly Mike Kelly: U.S. Team Sport's First Media Sensation and Baseball's Original Casey at the Bat) and John McGraw (Cap Anson 3: Muggsy John McGraw and the Tricksters: Baseball's Fun Age of Rule Bending). Given the requisite (nerdy) interest in his subject, Rosenberg's books are rich with detail and historical filigree. If you are the sort of baseball fan who enjoys Bill James' data-driven work, you might find the experience of reading Rosenberg's hyper-objective books similarly rewarding.

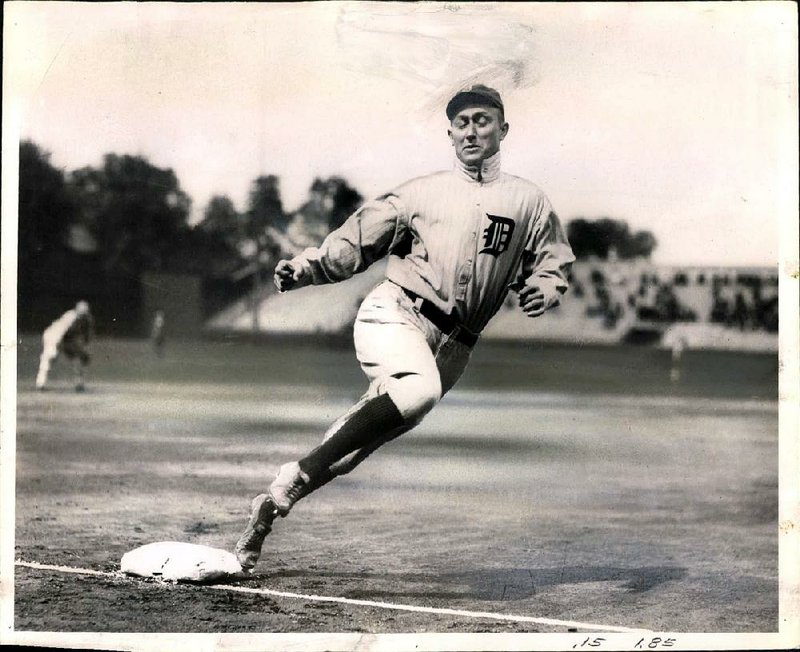

Now Rosenberg has turned his attention to another baseball figure, one much better known than Anson, and delivered the comparatively breezy single-volume Ty Cobb Unleashed: The Definitive Counter-Biography of the Chastened Racist (Tile Books, $32). Cobb is famous for a couple of things: He was baseball's best hitter before the emergence of paradigm-shifting Babe Ruth and for being a horrible, violent racist. That was exploited in Ron Shelton's myth-embracing 1994 film Cobb, which starred Tommy Lee Jones as a wife-beating, game-throwing spike-sharpener who sexually assaults a woman in a hotel room and confesses to murder.

Rosenberg, as much as is possible, assays these myths and returns a portrait of a man of his time as well as a useful and insightful critique into the literature surrounding Cobb. The author has not only produced his own scrupulously sourced biography -- he fact-checked all the other major biographies of Cobb since 1961's My Life in Baseball, Cobb's autobiography written with sportswriter Al Stump (whose 1994 book Cobb: The Life and Times of the Meanest Man Who Ever Played Baseball was the basis for Shelton's movie).

Ty Cobb Unleashed isn't the sort of thing that lends itself to a conventional review. So I asked Rosenberg about it.

Q: What's your background and how did you become interested in Ty Cobb -- who, I'm guessing, died before you were born -- and 19th-century baseball, a subject on which you are likely the world expert?

A: I'm a journalist by trade. Right after college in 1987, I moved from Long Island to Arlington, Va., where I still live. After one brief job for a newsletter called Superconductor Week, I wrote in Washington, D.C., for a Jewish wire service for about five years. Then in my full-time jobs, I moved to other fields, still generally having to do with writing or editing. In 1997, when under-challenged at my job, I visited the Library of Congress to consider researching 19th-century baseball, especially first basemen. I was hooked pretty fast, and wrote four books, but not on first basemen, that accounted for pretty much all of the library's newspaper holdings, and those of other libraries, relating to major league baseball from 1871 to 1900.

Q: Are you a fan of the modern game?

A: My interest in modern baseball hit a high and then crashed when I joined a fantasy baseball league in college. Instead of rooting for teams, I began rooting for individuals and sometimes for ridiculous scenarios to occur during a game; for example, a relief pitcher who you want to get a save could only do so if his team lost an eight-run lead and he was inserted. My dad at one point offered to pay me money not to watch so many games!

Professional basketball is the sport most similar to 19th-century baseball in allowing fans to see the players close up, including their personalities. I've seen pro basketball praised for that quality, but of course not for sharing that with early baseball.

I do have an unusual tie-in to the sport this century: I compiled the first official Boston Red Sox captain count that appeared in its annual media guide, after the Red Sox learned of my having disputed the official Yankees captain count when Derek Jeter was named in the Yankees one in 2003. My first book (Cap Anson 1: When Captaining Meant Something: Leadership in Baseball's Early Years) featured captains in early baseball.

Q: Unleashed is an interesting book in that it serves as a Cobb biography, an analysis of his cultural impact and a critique of the literature surrounding his life and myth. I remember reading Cobb's own book as a boy (with Al Stump), and Stump's revisionist one in 1994. I'm generally aware of the more recent works you write about in Unleashed. So, in your opinion, aside from Unleashed, which book provides the best -- fairest, most nuanced -- take on Cobb?

What do you see as the prime problems with other books on Cobb and with biography in general?

A: Cobb book authors each have their strengths. For a wild ride, if you don't mind inaccuracy, Al Stump's 1994 book is, hands down, the best. Even Cobb's own 1961 book, which he co-wrote with Stump, was regarded in its day as especially readable for a baseball biography. That's because Cobb liked to battle, and the book captures a lot of his spirit.

I don't think there is any dominant Cobb author for having aced Cobb. In large part, that is because, before me, they all shortchanged what was reported during his post-career. The chief Cobb biographer debate in my book is between two 2015 ones, a well-selling Simon & Schuster one by Charles Leerhsen and a relatively unknown one by Tim Hornbaker, from Sports Publishing.

The Leerhsen and Hornbaker books, to me, are stunning inverses. Leerhsen's style is opinionated and looking to make a splash by correcting history. Leerhsen once co-authored a book with Donald Trump (Trump: Surviving at the Top). Hornbaker's style is subdued, such as in trying to correct the record, but workmanlike in avoiding introducing errors. Correcting some of Leerhsen's findings might be the literary highlight of my book. That's because Simon & Schuster made great hay about how significant its book was especially for correcting Cobb's record on racism. My book, in essence, elevates Hornbaker as more accurate than Leerhsen on tricky subjects, especially racially on Cobb.

Q: You're very scrupulous with your sourcing -- it's never difficult to determine where you got a bit of information -- and transparent about your methods. I don't know that I've ever seen an author approach perfect objectivity so closely. Can you talk about your methods and philosophy?

A: I went for maximal transparency, of noting the names of my sources always in the main text, especially because that may be only fair when criticizing other authors. But I also chose the style because Simon & Schuster had marketed Leerhsen's book as authoritative. I think that publishers should take another look at their self-descriptions of a book as "authoritative" and "definitive" -- and if they are proven wrong to potentially offer mea culpas or rebates, and for book reviewers to be willing to revisit any previous unwarranted over-the-top praise.

Leerhsen pointed fingers in his book mainly at Stump and, on a few occasions, at 1984 author Charles C. Alexander. Well, based on there being so many favorable online reviews about the quality of Leerhsen's research, I can't wait to see what some of those same people will now say. That said, I have no idea if they will care to read another book on Cobb so soon! Novelty may matter more, leaving me with mostly new-to-Cobb readers.

Q: Is it fair to say that you've concluded that Ty Cobb was a racist, albeit one whose views evolved over the years?

A: Into the 1940s and until some point before 1952, Cobb was indeed a racist as far as being a supporter of institutional racism. My biggest finding was a pair of articles in 1946 by a highly regarded sports columnist (Bill Cunningham of the Boston Herald, born near Paris, Texas) in which he wrote about having overheard Cobb speak a few years earlier about his opposition to social equality on the ball field with black players.

Cobb had a mixed record on racism into the 1940s, and comes across much better racially in the 1950s. Leerhsen and, with less oomph, Hornbaker dispelled the case that Cobb could be considered a violent racist. There is a lot on both sides of the ledger, on whether Cobb was a racist, that one can still weigh. I even argue that one might still be able to call Cobb a violent racist in 1911 for, in playing a popular amusement park game called African Dodger, having no qualms about throwing a baseball at a black man's head, provided that the black man was willing, for money, to take the risk of being hit.

Q: Other writers have placed a lot of emphasis on the killing of Cobb's father by his mother. (In 1905, three weeks before Cobb made his Major League Baseball debut, Cobb's mother Amanda shot and killed his father, William Herschel Cobb, as he was climbing through their bedroom window. She told police she believed he was an intruder -- there was speculation that William believed Amanda was unfaithful and came through the window because he thought she was with her lover. She was ultimately acquitted of voluntary manslaughter.) Do you agree that this was a kind of primal wound that had a great effect on his personality? Or would you rather not speculate?

A: In my book, after saying that it's possible that some people might want to call him a violent racist as of 1911, I add, "It also could be argued that Cobb is a special case, entitled to leeway, because he had to cope with the worst possible violence: When he was 18 years old, his mom killed his dad. In other words, he was, through no fault of his own, desensitized to violence."

Q: Why should we care about Ty Cobb or Cap Anson?

A: I love the question! In essence, authors like me whose writing style is unconventional are saying, "If you can get used to the writing style, you are likely to learn a lot more than you would with books that go through mainstream publishers."

On Cobb, by being forced to weed through so much argumentation, I think overall my writing at times will come across as mainstream as can be. In my four 19th-century books, I focused a lot more on chronological presentation. But my underlying subject matter, I think, was inherently interesting, especially colorful 19th-century one-of-a-kind media stars Cap Anson and Mike "King" Kelly (Cobb and Babe Ruth are their 20th-century white equals), and the 1890s Baltimore Orioles.

While for example a mainstream book will try to set the scene for you for whatever's happening, my books merely present what's happening, and especially by quoting as much as possible. Baseball coverage in the 19th century was often written with a Victorian-era touch that mostly disappeared early in the 20th century. In this book, I still quote as much as possible at times -- not because the writing has charm, but because I think my paraphrases would sound dull and be less authentic. In any mythical listing of baseball book authors, I could be considered a "quote king," for better or for worse.

Q: Have you settled on your next project?

A: This may be a one-off book, in that I can't say that I love 20th-century baseball; the 19th is a lot more likable. Because my books hardly overlap with prior ones and I am far better an analytical writer than a narrative one, I think I will need to find some gaping hole anew to justify doing another.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 07/01/2018