One hundred years ago on Thursday, Mayor Charles Taylor promoted his stenographer into the post left vacant when his private secretary went to war.

Thus did Nellie Mae Bossart (or Nelliemae, Nellie May or, most likely, Nella May) make history in Little Rock.

The Arkansas Democrat noted her historicity Aug. 2, 1918:

Miss Bossart has been stenographer in Mayor Taylor's office for the past 18 months, and prior to that time was employed in the bank of the W.B. Worthen Company. Some of the work devolving upon the secretary will be performed by attaches of the health department. This will be the first time in the history of the city that a woman has been secretary to the mayor.

Of course a Nellie Mae could not be expected to carry quite the same load as a capable man like Charles E. Taylor Jr., the mayor's son and former private secretary, who had enlisted in the naval aviation service. Some office duties must shift to the health department and the city clerk, too.

By summer 1918, so many Arkansas men had been shipped off to war that women's employment opportunities were at high water. Of course, women worked outside their homes long before the Great War recast necessity as patriotism, but the war opened vacancies in office work, and women learned those skills and took those jobs.

You can trace the changing climate in the Democrat and Arkansas Gazette classifieds. In 1914, it was rare to see an ad like "Young lady stenographer; must be willing to work for small salary to start." Slightly more common were ads in which young lady stenographers sought jobs. But lady stenographers were almost as scarce as job offers for them.

In 1918, lady stenographers were invited to apply, and ads promised good conditions.

Ads from the U.S. Civil Service Commission urged patriotic women stenographers to visit or write the office at Third and Olive streets in St. Louis -- "Today! Now!" -- for information about government openings with salaries from $1,100 to $1,200.

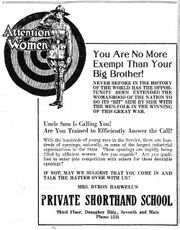

In Little Rock, private schools cited those salaries as they competed for female students with classes in bookkeeping, Gregg and Graham shorthand, advanced accounting, stenotyping and the use of something called "office appliances."

Draughon's Practical Business College, 112-114 E. Capitol Ave., offered instruction by mail or in person and did not charge extra for civil service training:

More than 250 students have joined our classes since June 1. The largest summer enrollment in our history; and there's a place for you.

Two Draughon's employees -- office secretary Byron Harwell and his wife, a teacher whose first name I do not know -- split from Draughon's to open the Mrs. Byron Harwell's Private Shorthand School in July 1918. But the school enrolled men as well as women, and by late August, it was his school, not hers, on the third floor of the Donaghey Building at Seventh and Main streets.

Miss Jennie Mitchell supervised instruction. She had been the head of the Underwood Typewriter Co.'s employment department.

She gives the student personal instruction in the use and care of the typewriter and modern office methods. Students finishing under Mrs. Mitchell are saved the embarrassment usually experienced in filling their first positions, by the ignorance of modern office methods.

Meanwhile, Byron Harwell's name was showing up routinely in churchy news, eventually including notices that he would preach.

In December, the Harwells closed their school. Byron explained in a two-column notice in the Gazette that he had been training to be a Methodist minister and had accepted a ministerial post out of state. Harwell's students would transfer to Draughon's.

ADVANCING

The same day it reported Nellie Mae Bossart's promotion, the Gazette reported that "Women Are Fastest Typists." In 1913, at New York, Miss Margaret B. Owen had tapped 125 words a minute for 60 minutes. Two men followed close behind her, hitting 120 and 117 wpm.

But at the world championship contest in Toronto in 1914, Owen retained her title, clattering away at 126 wpm for half an hour.

A man hadn't won since H.O. Blaisdell knocked out 110 wpm in 1910.

Now an army of fast-typing women was marching into offices, cleaning all the typewriters, taking over men's empty chairs. However would men's starving families survive when the men came home from war?

NELLA MAY

Since she had made history, I imagined it would be easy enough to trace "Nellie Mae Bossart" in the archives. I was wrong.

The few small items, which spelled her name various ways, convey that she was the daughter of W.P. and Mary Bossart of 1000 E. Ninth St. Her brother, Will, was in the 346th Infantry band and served in France.

She performed in shows with other young ladies of the YWCA. Once, she sang in the chorus of a "four-act musical extravaganza, minstrel and vaudeville review" for the Lions Club. And she belonged to a literary society, the Athena Delphian Chapter, with whom she was in a library program about "Prehistoric Man."

On July 27, 1918, she and 10 other young ladies of the Studio Club gave an informal program at the Officers' YMCA. The girls furnished refreshments, too, and about 125 officers were present -- with chaperones, of course.

But after June 1922, she vanishes from print. I felt sure she had married, and so I spent a bit of time on the public library's free account with Ancestry.com, looking up U.S. Census records. The spelling Nella May proved the most fruitful. Here's what I think I know:

She was born in 1892 in Herington, Kan., where she attended college. Her father worked for the Frisco railroad as a grain dispatcher.

In February 1925, she married Capt. Percy Langdon Blodget, a mining engineer who may have trained at Camp Pike during the war. He had graduated from Stanford University, where he ran track.

Married once before, he had one son. He worked for oil companies, and they lived in Beverly Hills.

Her parents remained in Little Rock. In 1930 she sent them a photo of her with Percy Jr. that wound up in the Gazette society pages.

After 42 years of marriage, Percy died in 1967. Nella May lived on at Los Angeles, dying in 1983. She was 90.

cstorey@arkansasonline.com

ActiveStyle on 07/30/2018