We are not innocent. Our attention is worth something. Corporations want to capture it and will pay for the opportunity to flash their logos and make their impressions. Most of us can't remember a time when it wasn't that way, if it ever wasn't that way, and some of us won't have any problem paying to see a feature-length Pepsi commercial/basketball comedy when Lionsgate's Uncle Drew hits theaters at the end of the month.

It's hardly the first time a movie has been made from slight material; Jim Varney's character a was created as a comic spokesman in 1980 to advertise an appearance of the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders at an amusement park near Bowling Green, Ky. He went on to become a spokesman for various products in regional television commercials -- the character ended up carrying 10 films (four of which went direct to video) and another six were reportedly in development when the chain-smoking Varney, who as Ernest filmed an anti-smoking spot in the '80s, died of lung cancer in 2000.

Arkansans will remember John Hudgens, a former TV newsman and political consultant, as The Big Man, a character confusingly similar to Ernest who served as the spokesman for North Little Rock's Twin City Motors in the '80s and '90s. Though this caused the producers of the Ernest commercials to threaten litigation, after Varney's death Hudgens portrayed Ernest in some TV spots -- you can watch one a demo reel of these spots on YouTube at youtube.com/watch?v=2pO26Qnct5A -- and in a CGI version.

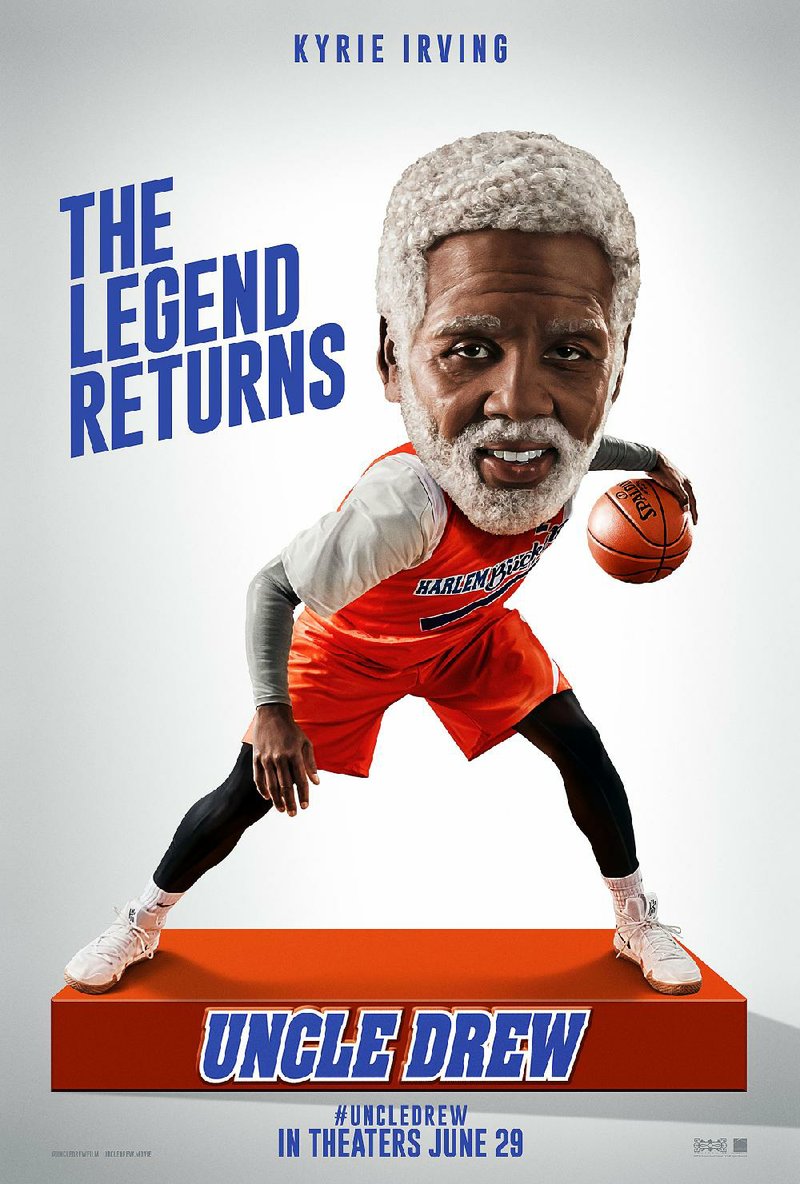

Anyway, the Uncle Drew phenomenon story began in 2011 when Kyrie Irving, the first pick in the 2011 NBA draft and a rookie guard with the Cleveland Cavaliers, agreed to appear in a commercial for Pepsi that ran during the 2012 Super Bowl. In the commercial, Irving appeared in old age makeup as Drew, a septuagenarian streetball legend. Irving is credited with creating the character and with writing and directing several of the series of ads, which were subsequently turned into a Pepsi-branded Web series.

Now they've stitched together a Blues Brothers "mission from God"-style script and recruited real-life ballers Shaquille O'Neal, Chris Webber, Reggie Miller, Nate Robinson and Lisa Leslie to be artificially aged to augment a host of D League-level supporting cast members that include Tiffany Haddish, Lil Rel Howery, Erica Ash, J.B. Smoove, Mike Epps and Nick Kroll.

It goes without saying that I haven't seen the movie yet -- it's not the sort of thing that makes the festival rounds or gets screened in advance; I'd be a little surprised if they aren't still tweaking it -- but I will say that Irving, who remains a likable figure despite some possibly serious flat-eartherism and the way he forced his way out of Cleveland, evinces a winning presence as Uncle Drew, even if his acting isn't on a par with that of his former teammate and possible arch-nemesis LeBron James.

If we want to get picky, James did this sort of thing back in 2006 with a series of Nike commercials called "The LeBrons" which featured him in five roles, including "Old Man" LeBron. Back in 2015, when Irving was still a teammate and the Cavs were world champions, a reporter asked if he would ever consider appearing in one of the Uncle Drew spots as Old Man.

"I don't do stuff with the other side," James said, "It's all Coke here, baby."

Coke and Pepsi have long been major players in the cinematic product placement, fighting for space on screen as well as behind the concession counter. The secret history of the 1996 summer face-off between Twister and Independence Day was the behind-the-scenes battle between the giant soft drink manufacturers. Pepsi cans were cut into little wings to lift the storm's sensors into the killer tornado in Twister; at a significant point in Independence Day Jeff Goldblum places a Coca-Cola can atop a captured alien spacecraft and directs Will Smith to shoot it off.

Americans don't drink as much soda as we did in the '90s, so maybe the stakes for Pepsi are heightened this year.

A major brand's involvement with a movie doesn't necessarily make for a bad experience -- The Legos Movie and The Legos Batman Movie make convenient counter examples. And product placement in movies has been around at least since 1927, when a shot of a Hershey bar (with almonds) was conspicuously inserted in the silent film Wings, the initial best picture Oscar winner.

In the '60s, the James Bond movies put nearly every one of the character's preferences up for auction: Name brands paid fees or other consideration to be Bond's cigarettes, whiskey, watch and car. (Bond drove an Austin-Healey until BMW supplied him with a snazzy convertible and designed a $15 million tie-in ad campaign around 1995's GoldenEye.) When Bond asked for a martini in Dr. No, it not only was of the vodka variety, it was specifically Smirnoff vodka.

Everyone has heard how M&M Mars turned down a chance for M&Ms to be featured in ET, so the alien munched a rival's product instead, boosting the sales of Reese's Pieces a reported 65 percent. (According to legend, the Hershey Co. -- which makes Reese's Pieces -- wasn't even contacted about its candy appearing in the film.)

Most of us would probably scoff at the idea that we are personally influenced by these crude attempts to confer cool onto material objects, but we might generally acknowledge that it works. The movies taught a lot of us how to dress, flirt, smoke and hold handguns sideways. (Also to open a bar fight with a head-butt, which isn't generally advisable unless you really know what you're doing.)

Product placement works in part because our decision to buy or not has more to do with whether we identify with a product than whether we like it. And when a character we identify with uses something onscreen, we subliminally begin to view using the product as a way of vicariously experiencing the character's life. This identification occurs even in experiments where the subjects are explicitly told the products shown onscreen had paid a fee to be featured. While we might express disapproval of these pay-for-play practices, there's evidence they work better than straightforward commercials.

It's interesting in part because a lot of us -- thanks to Netflix, Hulu and other digital avenues -- aren't subjected to nearly as many overt commercials as we used to be. I can go for weeks without seeing more than a handful of television commercials -- sometimes it even feels oddly refreshing to see the ads during a traditional, over-the-air broadcast of the Academy Awards or the like. And as more and more of us retreat from free advertising-supported channels, it only makes sense that the marketers are going to come after us aggressively.

On the other hand, some of us will pay to sit through a commercial.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

www.blooddirtangels.com

MovieStyle on 06/01/2018