The University of Arkansas, Fayetteville transfers hundreds of thousands of dollars a year to the nonprofit Razorback Foundation, raising questions about whether the booster club receives public money that would compel it to disclose business records it has shielded from the public, an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette investigation shows.

The money represents "donations" attached to some ticket prices -- for off-campus football games mostly -- and other contributions meant for the foundation but paid to the university, officials said. The university stores the money in campus accounts before settling up with the foundation, documents show.

It's one example of the intertwined financial ties between the nonprofit and the university's athletic department, which in turn relies on millions of dollars per year in foundation funding for an array of functions -- from paying the staff to upgrading facilities, printing promotional items and bankrolling holiday parties.

Arkansans have limited oversight on Razorback Foundation spending, even when it intersects with business at the state's largest public university.

[RELATED: UA nonprofit's $7M topped off '17 athletic payroll]

For example, the nonprofit last year declined to fulfill an Arkansas Freedom of Information Act request for its contract with a search firm to help find the Razorbacks a new head football coach. Separately, the university hired a different search firm to help vet candidates for athletic director -- the searches were happening at the same time -- and provided a copy of that contract when asked.

While the payments from UA to the foundation are not in dispute, the meaning of the term "public funds" in the context of the state's open-records law is contested. Even if the foundation's acceptance of the money sparked disclosure requirements, the range of the documents subject to release solely because of the money is difficult to pinpoint, law professor Robert Steinbuch said.

"This is where these things tend to get murky," said Steinbuch, an author of the Arkansas Freedom of Information Act textbook, who has called the transparency law a "bulwark" against public corruption.

Transparency questions apply to more than just the Razorback Foundation, which is the largest athletics foundation in Arkansas but has many peers in a state where nonprofits support dozens of public agencies, universities and their sports programs.

At least three dozen foundations statewide support public higher-education institutions or their athletic departments. They held a combined $1.8 billion in net assets in fiscal 2016, according to their tax filings, and their combined spending exceeded that of nearly every Arkansas city.

Arkansas State University and the Red Wolves Foundation have also withheld requested records -- specifically, loan documents related to a football stadium expansion project being led by the nonprofit.

Since last year, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette has reviewed roughly 1,000 pages of UA financial records and about 22,000 pages of emails to better understand the relationship between the university and its athletics booster club.

Much of the newspaper's reporting thus far has focused on whether the foundation essentially functions as a wing of the athletic department. The newspaper also argued that records related to former head football Coach Bret Bielema, who was the state's highest-paid public employee, are public business, as are documents related to finding his replacement.

The Arkansas Freedom of Information Act applies to agencies wholly and partially supported by "public funds" but does not define the term. It applies, in part, to records relating to the performance "of official functions that are or should be carried out by a public official or employee."

Arkansas courts, and unrelated laws, have addressed the meaning of "public funds" in various ways for different standards, but whether it applies, for open-records reasons, to money UA collects as part of ticket sales and later gives to the nonprofit is disputed.

Scott Varady, the foundation's director, and athletic department spokesman Kevin Trainor said transfers from UA to the foundation do not qualify as public money. Trainor said the money is "incidentally" processed by the university and set aside immediately for a future transfer to the foundation.

Open-records advocates are split on that question.

Steinbuch said the transfers represent "public funds" and that he believes foundation activities related to the money UA wires the nonprofit are subject to the transparency law.

"Very simply, it is money kept in the account of a public institution," Steinbuch said. "For the purposes of the [state Freedom of Information Act], those are public funds."

John Tull, general counsel for the Arkansas Press Association who specializes in open-records issues, disagrees.

"I don't think it is ever public money," Tull said, suggesting that the nonprofit may have grounds for a lawsuit should UA withhold the transfers. "I think it is consistently the foundation's money."

Tull, however, has maintained that an organization does not need to receive public funds to be subject to Arkansas' open-records law. If a nonprofit like the Razorback Foundation is "so entwined that essentially it's the same" entity as the public agency it supports, its records are subject to the law.

"If I were representing you in that case, I would just ignore the public funds," Tull said. "That's not required."

HOW THE TRANSFERS WORK

Razorback fans who wish to purchase athletics tickets in many cases must also make a contribution to the Razorback Foundation.

Through a $12 million seat-assignment contract with the university, the foundation has authority to determine where people sit at sporting events. The quality of fans' seats is largely based on how much money they give the nonprofit and for how long they've been regular donors.

Most of the time, for on-campus tickets, fans make a season's required donation separately from their ticket purchase. One might, for example, send a check to the foundation and a check to the ticket office to buy season football passes. If a fan does not pay the donation, the athletic department will withhold the tickets, emails show.

For games outside Fayetteville, fans can bundle both payments in a single transaction. One case, which makes up the largest share of the UA-to-foundation transactions, is the Razorbacks' annual football game in Arlington, Texas, where they play Texas A&M in the Southwest Classic.

Fans who buy tickets online are informed that a portion of the total cost -- $100 for $225 tickets or $175 for $300 seats -- is a "tax deductible donation which qualifies for Razorback Foundation priority points." Beyond that, nothing before the point of purchase expressly says the money is going to the nonprofit.

When the payments are made jointly like this, the money goes to university accounts, with donations split from the ticket price by the third-party ticket-sales vendor, according to officials.

UA later, often months afterward, sends the money to the foundation.

UA records show that the money is typically classified as a liability, "deferred revenue" -- which essentially means a bill to pay -- when it's in the school's account.

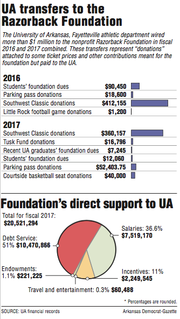

In fiscal 2016, the university wired at least $522,000 to the foundation -- $413,355 related to football ticket donations, $18,600 related to parking-pass donations and $90,450 that the UA collected from students who became foundation members, according to records obtained through the Arkansas Freedom of Information Act.

The following year, UA transferred at least $488,000 to the foundation, records show. Again, donations for football tickets made up the majority.

Varady, who worked at the Fayetteville campus as a UA System attorney before taking the top foundation job, said the system's general counsel reviewed the Southwest Classic ticketing process before it was implemented but did not issue a "formal written opinion."

Speaking generally, Trainor said, the donations are processed through UA as a matter of convenience for fans -- to "streamline the payment process for their ticket purchases."

"These amounts do not constitute 'public funds' because they never belonged to the University," Trainor said by email. "The moneys were never held out to be, intended or solicited for the University."

DEFINING 'PUBLIC FUNDS'

Both Varady and Trainor cited the 2016 Arkansas Supreme Court ruling in McCafferty v. Oxford Am. Literary Project, Inc. to support saying that athletic department money, specifically from ticket sales, does not qualify as "public funds."

Essentially, their point is that UA athletic department revenue from ticket sales qualifies as "cash funds" and not "public funds." The distinction is that the source of the money is not taxes, but what's generally referred to as "auxiliary activities," or other revenue streams.

In essence, cash funds are money that is not tax-derived and not deposited in the state Treasury.

In the context of athletics, auxiliary activities include ticket sales, concession revenue and private gift support, Varady said. He and Trainor have also repeatedly stressed that the athletic department is self-sustaining -- meaning it does not rely on direct taxpayer support or student tuition or fees. The department last year transferred $3.2 million to UA's general fund.

"As defined by the Arkansas Supreme Court in McCafferty, the funds that support the Athletic Department are 'cash funds' -- non-taxpayer dollars -- and not 'public funds' -- tax dollars maintained in the State Treasury," Varady said by email.

McCafferty, as Varady and Trainor said, distinguished between tax revenue and cash funds, but specifically in the context of whether someone could file an "illegal exaction" case -- or a lawsuit alleging that a public agency misspent public money. The case did not involve open-records issues.

"The only issue for this court to decide is whether McCafferty can maintain an illegal-exaction lawsuit to challenge an allegedly improper expenditure from [the University of Central Arkansas'] 'cash fund,'" the decision says.

In fact, the court's opinion, citing its own precedent, says that cash funds are public funds subject to "oversight."

"However, these cases do not indicate that a fund merely qualifying as 'public money' or a 'public fund' is sufficient to support an illegal-exaction claim," it says. "Rather, these cases denote that cash funds and public monies are subject to some governmental regulation and oversight even though they are not comprised of tax-generated dollars."

Several decades of the high court's precedent have broadly considered cash funds to be public money. An earlier decision cited in the McCafferty ruling regarding that question is the 1974 case Parker v. Ark. Real Estate Comm'n. That case, citing an opinion from the 1940s, said specifically that "all cash funds of state agencies are public monies."

Trainor additionally highlighted the definition of "public funds" in Arkansas' procurement law, which also does not address open-records issues.

Arkansas Code Annotated 19-11-203 defines public funds as including "cash funds of state agencies" but specifically exempts "revenues derived from self-supporting enterprises which are not operated as a primary function of the agency."

Steinbuch said the law could be flipped against the foundation. Legislators specifically exempted cash funds as a form of public funds in this instance but did not address it in the open-records law. It can be argued the omission was intentional, he said.

"With that said, I still think that argument of theirs is the only one that's not ridiculous," he said. "I think they can make it. I think it's a losing argument."

In another court decision, the Arkansas Supreme Court in its 1993 Sebastian County Chapter of the American Red Cross v. Weatherford opinion ruled that indirect benefits do not qualify as "public funds" -- the issue in that case was whether the Red Cross' lease of public property at a below-market rent subjected it to the open-records law. The court reached that conclusion after checking Black's Law Dictionary, 6th Edition, for the definition of "public funds."

"Moneys belonging to the government, or any department of it, in hands of public official," the definition read, according to the court's opinion.

Information for this article was contributed by Aziza Musa for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

SundayMonday on 06/03/2018