In March, between the time 17 high school students and educators were massacred by a lone shooter in Parkland, Fla., and 10 more were killed in Santa Fe, Texas, a school district in Pennsylvania furnished all of its 200 classrooms with weapons--in this case, buckets of rocks for students to throw at would-be school shooters.

A few weeks later, another of the state's school districts armed its teachers with miniature baseball bats. One can hardly blame school administrators for trying to do something, anything, to protect the children and themselves at a time in which school massacres have become commonplace enough to characterize as "a unique American ritual."

On May 25 it happened again, when a student at an Indiana middle school opened fire, wounding a student and a teacher.

I do not yet keep rocks in my philosophy classroom, but it would be a blunt visual reminder of the risk now associated with being a group of people who predictably gather in conference centers, restaurants, offices, subways, and along streets and sidewalks. In a very fundamental way, the trust that once allowed us to interact freely in public spaces has been broken.

In thinking about this issue, I recently returned to a 1937 treatise called Rinrigaku, meaning "the principles that allow us to live in friendly community" by the late Japanese moral philosopher and cultural historian Watsuji Tetsuro. This is how he describes that intricate web of trust:

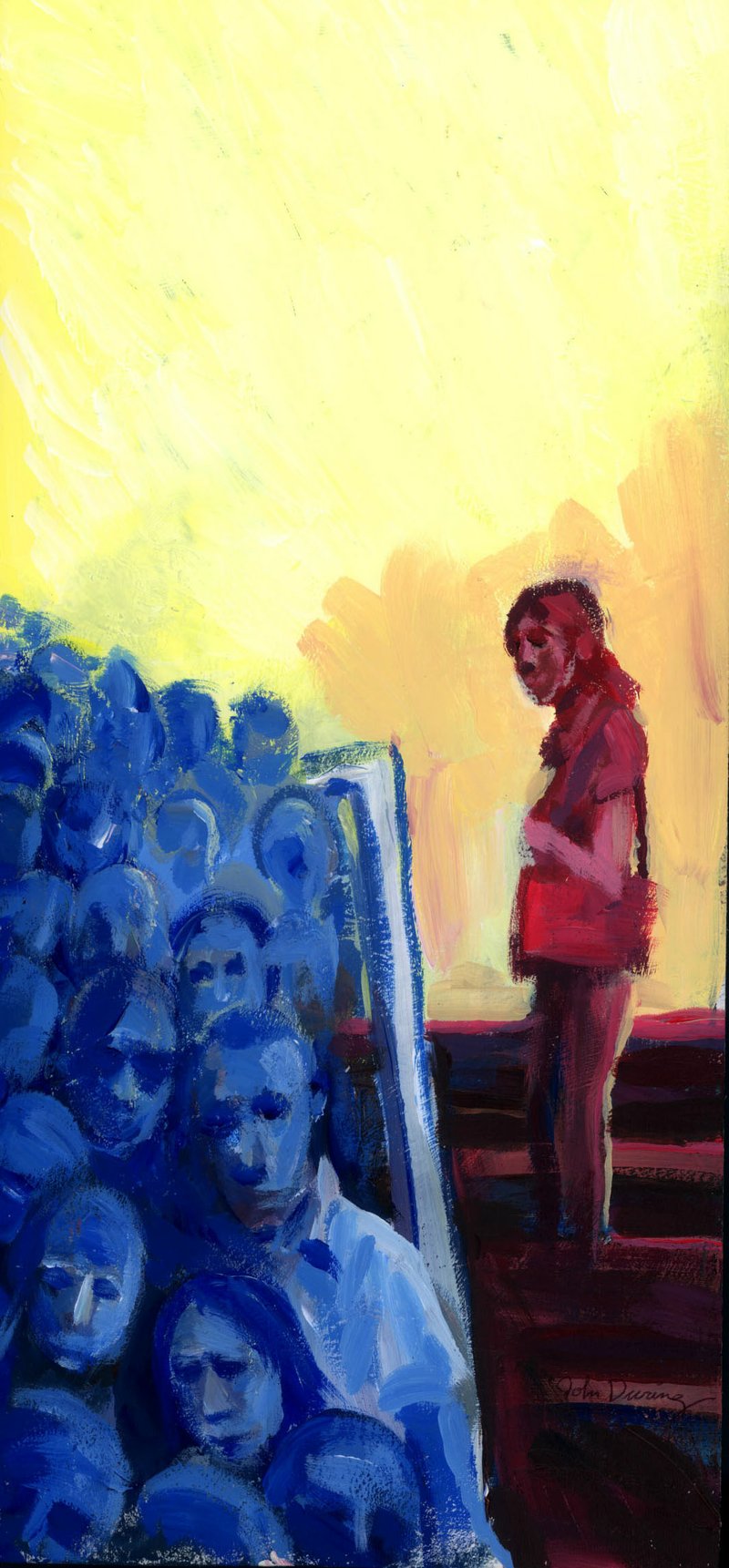

"Even a cursory glance at our everyday life is enough to show just how much trust is in evidence. This is no less the case even with life on the street, where the connection of human beings with each other is weakest, than with the intimate communal

life of a family or friendly relationship. People walk in the midst of a crowd without having to be prepared to defend themselves. Precisely because they take it on trust that strangers have no more intention of inflicting a wound on others than they themselves have, they are able to walk at ease with an unguarded attitude."

When I observe my own everyday life in the wake of mass shootings, bombings and vehicle attacks, I find that basic element of trust absent. I walk ill at ease and read articles like "How to Protect Yourself During a Mass Shooting" written by the former Marine Ed Hinman after 26 people were killed by a shooter at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas: "Mass shootings can happen anywhere, at any time. It's imperative that everyone know how to react."

I dutifully watch a video posted with the article called "Run, Hide, Fight." The best option is to run, and we should encourage others to flee with us, but "don't let their indecision keep you from going." The illustrated slides instruct us to choose a route carefully, think unconventionally, consider jumping out a window. Be quiet and stealthy. If I can't run, I should hide, and make a plan while under a desk in a barricaded room. What plan could that be?

If that fails, fight. Use the element of surprise against the shooter: create chaos, swarm, move the weapon away, attack. "You must be an active participant in your own survival," Hinman writes. And this means being prepared to grab a fire extinguisher, scissors, or a pen "to incapacitate him with speed, surprise and violence of action."

Perhaps others don't hear the chilling ring of remarks like, "I'm already executing my evacuation plan before anyone else." I wonder if theaters will increase ticket prices for exit row seats. Hinman makes an appeal to a very American way of thinking, wherein the individual asks "How can I protect myself" without asking what it would take for us to shape our shared world into a fit home for collective life.

Unfortunately, the loss of trust in public space does not reduce the risk or mitigate the danger of being in that space. Lost trust creates moral and even mortal dangers, including the ways we potentially trample ourselves and others through fear and preparation for violence in public spaces. Hinman tells us that if he observes a person behaving strangely, "I'll listen to my intuition like any animal bent on survival." Does he not remember Trayvon Martin, whose concealed Skittles triggered the survival instinct of a hyper-vigilant citizen?

The post-9/11 "If you see something, say something" campaign has increased pressure to report anomalies and unconventional behavior, which is certain to intensify in response to serial mass shootings. Someone in my friend's neighborhood called the police on him for taking a walk with his newborn child in a front carrier because they thought he was casing the street with a fake baby. On another day, my sister watched the police arrive at a playground to question the mother of an autistic child whose messy hair, mismatched clothes and erratic movements caused someone to think they had better say something, but not to the mother who was supervising her child.

Where the strange registers as dangerous and the feeling of being threatened sanctions pre-emptive action, public spaces become untrustworthy environments for those who are even slightly unconventional (or insufficiently white). Largely futile conformity-enforcing vigilance undoes public space as a place for free exchange, for encounter with difference, and for adventure.

We could make our public spaces more trustworthy for everyone by eliminating access to military-style weapons and drastically reducing the number of guns in circulation. The attraction of pseudo-expert survival advice may signal hopelessness--the belief that it is either too late or not yet possible to aggressively regulate guns. Or it may be that responses that require reliance on the political cooperation of strangers are an unwelcome reminder of how deeply we depend on others for real security.

In his book Torture and Dignity, philosopher J. M. Bernstein has pointed out that relations of trust are so foundational to everyday life that they remain largely invisible until they begin to break down. Bernstein calls flights from our inescapable vulnerability fantasies of independence: "Radical dependency" is part of the human condition from birth to death, "no matter how absurdly and desperately this is denied and repudiated."

Distrust triggered by random violence doesn't select precise targets. It spreads ambient anxiety incoherently. It digs up deeply entrenched bias and paranoia and in the imagination makes enemies not of the citizens of some distant tribe or nation but of those to whom we are most closely bound.

Fortunately, the imagination can be retrained. I hear the words of emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius: "We were born for cooperation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids, like the rows of upper and lower teeth," which suggest that an individual cannot act in a fully human way without trusting other people just as one foot, hand, eyelid or tooth cannot walk, wash dishes, blink or chew on its own.

We magnify our powers through trust in others, and we atrophy them through distrust. The solution to broken trust caused by gun violence may be investing more trust in each other, which is intuitive and counter-intuitive at the same time.

In my son's storybooks a lion helps shelve books at the library, bears sit around the breakfast table, and wolves give goodnight kisses after howling at the moon. It is easy to imagine the wild animals in the books as tame, trusted.

But at school, at the movies and at church there are fierce human animals roaming and hunting, and everyone tells us that we had better learn how to run, how to hide or how to make ourselves fierce. We can't yet imagine a way to disarm them and find our way back to trust.

Mavis Biss is an associate professor of philosophy at Loyola University Maryland.

Editorial on 06/10/2018