"To be succinct, concise and brief:

I do not care for Miss O'Keefe"

-- Dwight Ripley, "Alphabetical Guide No. 2," circa 1952

So ubiquitous as to seem invisible, it is hard to know what one thinks of Georgia O'Keeffe.

We know the name and the reputation, the flowers and desert landscapes. But there is more than a hint of Southwestern kitsch in there, and discussions of the flowers manage to come back to the artist's denial of any intentional evocation of the gynecological. In this age where basketball players and presidents aspire to become nothing more than brands, it is tempting to regard O' Keeffe (1887-1986) as less an agent of creation and more a designer's marque.

Most of us first encounter her work in reproduction, in posters framed in the bedrooms of maiden aunts or in sets of cards of desert scenes sold in museum gift shops. There is an American tang in the name, four declarative syllables presenting as a trademark. You would have heard the name even if you'd never seen her work or her image.

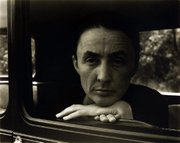

Which is unlikely. O'Keeffe was one of the most photographed women of the 20th century thanks to her relationship to photographer Alfred Stieglitz. And you may have heard a version of that story as well.

Stieglitz was not only an artist, but an important art promoter and patron, one of the most powerful figures in the Manhattan art world. In 1916, when he was 51 years old and at the height of his influence, he was given a portfolio of charcoal drawings by an unknown 28-year-old art teacher working in the Texas panhandle. "At last, a woman on paper!" he's said to have Eureka-ed. He immediately began to show the work in his gallery, without informing the artist.

A patron at the gallery, a friend of O'Keeffe's, happened to see them. So the artist traveled to New York to chew him out for showing her art without permission. "I am Georgia O'Keeffe and you will have to take these pictures down," were allegedly her first words to him.

But something happened between them. Back in Texas, she wrote him: "I'm getting to like you so tremendously that it some times scares me."

By 1918, Stieglitz had arranged studio space for O'Keeffe in New York; soon he left his wife and moved in with her. By 1924 they were married, and from 1916 to his death in 1946 they wrote more than 25,000 pages of letters to one another. He photographed her more than 300 times. (And eventually was unfaithful and cruel to her, taking up with 22-year-old Dorothy Norman and mounting an exhibition of unflattering photographs of a sun-weathered O'Keeffe. But she was with him on his deathbed.)

It is not difficult to believe that O'Keeffe benefited greatly from her association with Stieglitz; it's difficult to uncouple the art from the mythology. Not even O'Keeffe could quite do it. Christine Taylor Patten, a painter who worked as O'Keeffe's caretaker during the last years of her life, remembers a conversation from 1984 when O'Keeffe lamented that she wished she'd "kept a diary" because "I think I know now my life is never going to look right."

. . .

While fame and familiarity have warped whatever view we might have of O'Keeffe, one way to look at something hot and bright is through the filter of others. That's one reason to investigate The Beyond: Georgia O'Keeffe and Contemporary Art at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville. The exhibition will be on display until Sept. 3 before moving on to the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, and in 2019 to New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut.

It juxtaposes 36 works (many from Crystal Bridges' collection) by O'Keeffe from various points of her career with the works of more than 20 working artists, chosen specifically by Lauren Haynes, Crystal Bridges curator of contemporary art, and Chad Alligood, an independent curator, for ways their art relates to and comments on O'Keeffe's.

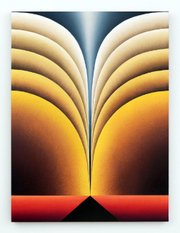

There are some obvious echoes between O'Keeffe's New York night scene Radiator Building--Night, New York, which she painted from her window at the Shelton Hotel in 1927, and Israeli American painter Sharona Eliassaf's Stars to Dust, Dust to Stars. They're both geometric paintings of stylized skyscrapers that simplify the articulated details of the structure with sharp lines. But Eliassaf's playful, sunny palette and wry introduction of pop culture (Wheel of Fortune-style panels) contrasts with O'Keeffe's elegant Art Deco-ish treatment. (Which in turn rhymes with Loie Hollowell's 2016 painting Yellow Mountains, which marries the Precisionist lines of Radiator to O'Keeffe's preoccupation with natural forms and desert scapes.)

And seen outside the context of O'Keeffe's Yellow Jonquils #3, Jennifer Packer's small (and untitled) depiction of yellow flowers at a funeral might not evoke O'Keeffe at all, or might in its austere modesty seem to rebuke the supersized blooms. But side by side, you feel the connection.

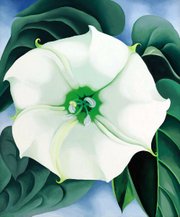

One of the things often said about O'Keeffe's work, sometimes even by her enthusiasts, is that it tends to look better in reproduction than in person. Cameras love her matte finishes and the meticulous brushwork that, when closely considered, betrays the effort. But, to borrow a term from Erica Jong, zipless art is as illusionary as Hollywood romance, and there's something about encountering an iconic painting like Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 (1932) up close and in person that delivers it from the realm of cliche. It helps to see how the paint was bossed around the canvas, to have confirmation that human hands intervene to make the work.

Regardless of whether you have a taste for O'Keeffe's work or not, one of the things The Beyond illuminates is how she prefigured the modern preoccupation with freighted framing, a strategy of choosing just how much (and how little) of a subject to show. She picks her angles like a canny cinematographer, and if we don't quite believe her protests that a canyon is just a canyon, maybe we can appreciate her making us collaborators in her art. As the exhibition's title suggests, we always have the sense that the world continues beyond the frame of an O'Keeffe painting.

That's one of the things at play in Tulsa artist Mark Lewis' Peoria Avenue #7, a piece that many might find familiar (it won the Arkansas Arts Center Delta Exhibition's Grand Prize in 2013). It's an oversize work constructed of strips of paper of varying grades of gray, cut and glued into place to create a realistic image of a street scene, assembled -- collaged -- from life.

There's that same sense of selection in Cynthia Daignault's Light Atlas, a series of 360 small paintings that chronicle a six-month road trip she made across the United States. She stopped to paint a new panel every 25 miles, snapshots of her progress. The Beyond balances Daignault's work with O'Keeffe's Cebolla Church, a 1945 painting of a sun-washed New Mexican mission. And while O'Keeffe to some degree anticipated photorealism, she also worked in expressionist and abstract modes, to the point that Kim Keever's 2017 photograph Abstract 30682b fits nicely with some of O'Keeffe's Wassily Kandinsky-inspired experiments with synesthesia.

Maybe the work most overtly influenced by O'Keeffe is Anna Valdez's slyly subversive Deer Skull with Blue Vase, a tableau framed against floral wallpaper that seems to be in direct conversation with O'Keeffe's From the Faraway, Nearby to which it hangs perpendicular. It could be read as a comment on the co-opting of O'Keeffe's themes by those maiden aunts through which we first encountered the artist.

. . .

When you go looking for the Great American thing, as O'Keeffe famously set out to do, you must be prepared to encounter, and maybe embrace, consumer kitsch.

O'Keeffe divides people; it can be argued that she's one of the defining artists of the 20th century, the "mother of American Modernism," a proto-feminist whose best work (which includes some of her last work, rendered after she started going blind) belongs in the pantheon of the best work our kind has ever done.

On the other hand, familiarity and popularity never enhance an artistic reputation. Ask Elvis Presley, who some people insist is still available, about how one's legend obscures one's art.

It all comes down to taste. Some find her work thrillingly spiritual, others perceive in it a suggestion of a depth that isn't there. And while O'Keeffe always insisted that her biography, her personality -- the "where and how" she lived -- was unimportant, her myth overshadows her work. You can love some of it, yet still suspect that it's rather minor.

But what's undeniable is that it persists. It's what these (relatively) young artists have taken up. It's what goes forth. Not many remember Dwight Ripley now -- he doesn't even rate a Wikipedia entry -- though he was a better artist than he was a poet (his drawings were "pioneering in the use of colored pencil") and an even better botanist, with several important scientific discoveries to his credit.

No one really cares that he didn't care for Miss O'Keeffe.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 06/17/2018