Our story so far: Recovering from a heart transplant, our critic Piers Marchant is spending his post-op convalescence filling in gaps in his cinematic education by watching in 30 days 30 "important" films he'd somehow missed. This is his second report.

The second week of this experiment hit a major technical snag: My Blu-ray DVD player died in inglorious fashion, just as I was about to watch Blow-Up. Dealing with Sony's support team has been less than rewarding to this point, but many thanks to my friend for loaning me her family's player so I could at least complete this week's list. Next week, I will hopefully be back on track, but decidedly not with a Sony player. Later note: And also not with the new unit I ordered, which got stolen off of my front stoop upon delivery. Sigh.

To repeat: Just to keep things relative, I am awarding a score on a 10.0 scale at the end, along with what I'm calling a Relevancy score out of five stars. In other words, even if I wasn't wild about the picture, I still believe it is an important film for me to have seen. Expect a lot of fives on that category.

1. Make Way for Tomorrow (1937): The setup might sound preternaturally hokey -- an elderly couple (an excellent Beulah Bondi and Victor Moore), after losing their house to the bank, are forced to separate and move in temporarily with two of their five reluctant children.

Living without each other for the first time in 50 years, they grow more miserable and despondent, aided on that score by the bitter, put-upon attitude of their children, who all have lives of their own that they don't want intruded upon.

Leo McCary's film, which could easily have wallowed in sentiment and false good cheer, shockingly stays its perilous emotional course. We watch in abject horror as Bart and Lucy are made to feel more and more unwelcome and extraneous in the homes of their children. One of them has no children, only a galling and hideous husband utterly uninterested in helping anyone else out.

As Bart and Lucy are reunited for one last evening together before Bart gets shipped out to California with yet another of their ungracious children, they blow off the planned dinner with the kids and instead spend their limited time together sweetly reliving some of the highlights of their honeymoon in New York.

Brave, unflinching, and absolutely devastating emotionally, the film never turns away from its protagonists' fate or besmirch itself with some smarmy Hollywood hokum or deus ex machina, and, as such, remains every bit as vital and honest as it was more than eight decades ago. Like one of Chekhov's short stories, the film's harsh-but-fair truth is so searing and real, it will never feel dated.

Score: 9.7/10

Relevancy: 5/5

2. Gaslight (1944): An exercise in revulsion and loathing: You so despise the controlling, hateful character of Gregory (Charles Boyer), who essentially locks his adoring wife, Paula (Ingrid Bergman), in her London home, doing everything in his power to drive her to madness by making her think she's becoming forgetful and unglued, you spend half the movie wanting desperately to be able to punch him in the face.

With his indeterminate Eastern Euro accent, even the way he beseechingly calls her name -- "POH-la" -- as he seems to do nearly every sentence he utters from his repugnant lips, becomes enraging. Naturally, the thriller, masterfully put together by George Cukor (The Philadelphia Story), absolutely encourages this sort of furious response: Thankfully, we are meant to hate him every bit as much as we need to, in order to survive to the third act, whereupon poor, suffering Paula gets some backup, from Detective Cameron (Joseph Cotten, playing yet another character who meets a woman once and can't get her out of his mind).

In the meantime, Cukor's camera seems to linger over Boyer's smug face and imperious features, practically daring you to jump out of your seat and paste him a good one. It's infuriatingly riveting stuff.

Score: 7/10

Relevancy: 3/5

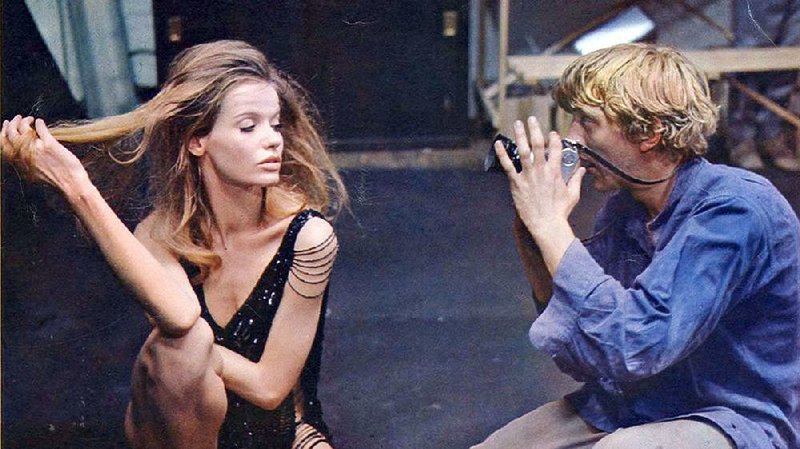

3. Blow-Up (1966): High-fashion photographer Thomas (David Hemmings) has a life of booze, casual sex, and endless work for which he feels more than entitled to be something of a twit. His success is evident in his manner, which is generally brusque and condescending, but shooting an unsuspecting couple in a London park on a whim one morning, he thinks he may have stumbled onto recording a murder taking place.

Michelangelo Antonioni's film, which serves as a pristine time capsule of swinging London on the fringes of the youth rebellion that marked the age, is anything but plot-driven. Thomas' relationship to reality -- what he thinks he's shooting versus what he can see in the edges of his frame after enhancing the image and blowing up the size into almost totally abstract grains -- is put into question, and his reaction suggests a disassociation from reality. (He never bothers to call police, even after discovering a body.)

Fittingly, then, the film ends enigmatically, with him throwing an imaginary tennis ball to a pair of mimes, and then the camera shot places him alone in a sea of green grass, no other figure or structure around him, as he, too, fades out of the scene.

Score: 8.3/10

Relevancy: 4/5

4. Notorious (1946): I would have to deem it as somewhat lesser-Hitchcock -- apart from everything else, practically every agent and counteragent in this spy thriller acts like a complete imbecile, and gets away with terrible decisions and worse schemes -- but there are certainly significant highlights.

Included on that list, the irrepressible Ingrid Bergman (witnessing the peak of her powers), a suitably charming Cary Grant (even if his character spends much of the film acting like a petulant 13-year-old spurred at the eighth-grade dance mixer), and just enough camera highlights, including a dizzying plunge from the top of a high, rounded staircase over a party crowd, down to the fine detail in one character's hand, standing in the middle of the giant reception hall, to keep you engaged. Inessential, but well worth the watch.

Score: 6/10

Relevancy: 3/5

5. Pather Pachali (1955): The modern influence of Indian master auteur Satyajit Ray can be seen in everyone from Spielberg to Yimou Zhang. His most famous work, The Apu Trilogy, begins with this film, an exceedingly rich and humane narrative about an impoverished Bengal family living hardscrabble in the small ancestral home village of Harihar (Kanu Bannerjee), a priest desperately trying to find work to sustain his wife, Sarbojaya (Karuna Bannerjee), and two children, older sister Durga (Uma Das Gupta), and young son Apu (Subir Banerjee).

Ray's film is much less focused on Harihar, however, and stays at home with the family he's forced to leave behind when he goes out in search of work. With things getting ever more desperate at home, and Sarbojaya growing increasingly anxious she won't have enough money to feed the kids, the film's push/pull style, contrasting Sarbojaya's suffering and the kids' romping around the landscape as joyous adventurers, is steeped in a drape of irony that powers the proceedings -- however seemingly small and understated -- into something a good deal more affecting.

Ray, who famously shot this, his directorial debut, without having directed anything before, utilizing a cinematographer who had never shot a film, and a cast that hadn't even screen tested before showing up on set, spent five harrowing years making the film, losing funding on more than one occasion, before releasing what is now considered a masterpiece.

Shot on less than a shoestring, on the strength of the director's vision, it's a testament to artistic ambition, even in the face of oppressively bad circumstances. I greatly look forward to watching the other two films in the trilogy after I complete 30x30.

Score: 9.5/10

Relevancy: 5/5

MovieStyle on 06/29/2018