BEIJING -- China's National People's Congress on Sunday voted in favor of a plan to abolish presidential term limits, making it possible for President Xi Jinping to stay in power indefinitely and cementing a shift in Chinese politics.

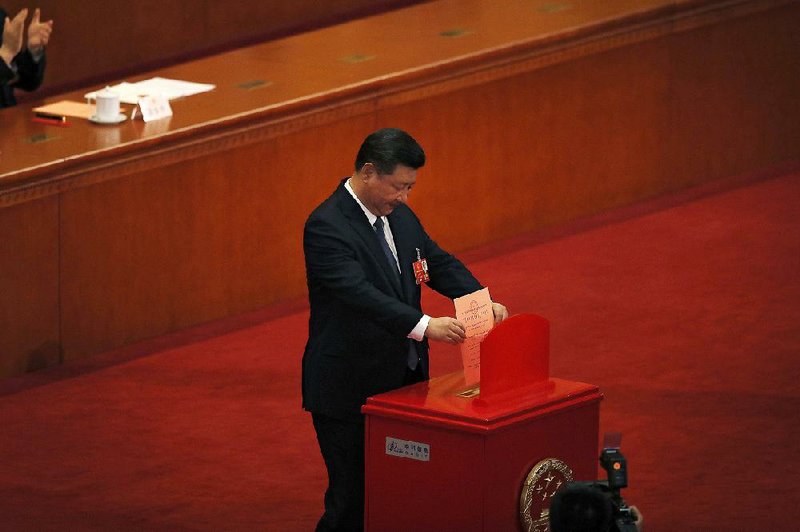

At Beijing's Great Hall of the People on the western edge of Tiananmen Square, 2,964 delegates cast their votes, with 2,958 voting in favor of the constitutional amendment, two against, three abstentions and one invalid vote.

The amendment was among a set of 21 constitutional changes approved by the congress, further underscoring the total dominance of Chinese politics possessed by the 64-year-old Xi. He serves simultaneously as the head of state, leader of the ruling Communist Party and commander of the powerful 1 million-member armed forces.

The ballot came two weeks after Communist Party-controlled media announced the proposal. It was the clearest evidence yet that Xi plans to rule beyond the end of this second term, in 2023, taking China back to the era of one-man rule just as it steps up its role in global politics.

The delegates applauded briefly when an official declared the vote was over, and clapped again for 20 seconds when the outcome was announced.

"No disagreements, no different points of view," Ma Shunnan, a delegate representing the Chinese navy, said in a brief interview shortly before the vote. "Every delegate is on the same page."

"It means that Xi is now unquestionably a Leninist strongman," Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at SOAS University of London. Xi, unlike his predecessor, is not first among equals but "lord and master of them all."

The vote upends a system enacted by former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in 1982 to prevent a return to the bloody excesses of a lifelong dictatorship typified by Mao Zedong's chaotic 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution.

"This marks the biggest regression in China's legal system since the reform and opening-up era of the 1980s," said Zhang Lifan, an independent Beijing-based political commentator.

"I'm afraid that this will all be written into our history in the future," Zhang said.

BACK TO FUTURE?

Though state-controlled media insisted that the constitutional changes had "won the hearts of the people," the news spurred a wave of public worry about a return to the despotic politics of the past.

"It's a historic retrogression," said Li Datong, a former editor of China Youth Daily, a state newspaper.

"Throughout history, only Chinese emperors and Mao Zedong had lifelong tenure until their deaths," Li said. "And what came out of that was a disaster for the society and many painful lessons."

"If the constitution of one nation can be amended by the most powerful person according to his or her will, the constitution is not a real constitution," said He Weifang, a law professor at Peking University.

"The legacy of Deng Xiaoping's efforts to avoid lifelong presidency have been abolished completely," he said.

The move has crushed faint hopes for political reforms among China's embattled liberal scholars and activists, who now fear even greater repression. China allows no political opposition in any form and has relentlessly persecuted independent groups seeking greater civic participation.

In a sign of the issue's sensitivity, government censors have aggressively scrubbed social media of expressions ranging from "I disagree" to "Xi Zedong." A number of prominent Chinese figures have publicly protested the move, despite the risk of retaliation.

Nevertheless, Xi's confident, populist leadership style and tough attitude toward corruption have won him significant popular support.

Zhao Minglin, 32, a vice president of a Beijing investment firm, said it would be easier for Xi to carry out his vision of raising living standards if more power were concentrated in his hands.

"I will definitely support this constitutional amendment and this government. This is a powerful and strong government," Zhao said. He added, however, that he was concerned that the public discourse lacked a space for dissenting voices.

Some Chinese people worry that the abrupt change augurs a return to the strife over succession that troubled the eras of Mao and Deng.

"Abolishing the term limit on the leader of state does not make a leader but a usurper," Wang Yi, a former law lecturer who now works as a church pastor in Sichuan, said via a phone message. "Writing a living person's name into the constitution is not amending the constitution but destroying it."

OTHER AMENDMENTS

Since his ascendance in 2012, Xi has moved quickly to consolidate power at home and trumpet an ever-grander vision of China's place in the world.

Defying norms of collective leadership established over the past two decades, Xi has appointed himself to head bodies that oversee national security, finance, economic reform and other major initiatives, effectively sidelining the Communist Party's No. 2 figure, Premier Li Keqiang.

In addition to scrapping the limitation that presidents can serve only two consecutive terms, the amendments also inserted Xi's personal political philosophy into the preamble of the constitution, along with phrasing that emphasizes the party's leadership.

Another authorized a new investigative agency to step up the anticorruption drive that Xi has used to consolidate his control over the party.

The slide toward one-man rule under Xi has fueled concern that Beijing is eroding efforts to guard against the excesses of autocratic leadership.

The head of the legislature's legal affairs committee, Shen Chunyao, dismissed those worries as "speculation that is ungrounded and without basis."

Shen told reporters that the party's 90-year history has led to a system of orderly succession to "maintain the vitality and long-term stability of the party and the people."

"We believe in the future that we will continue with this path and discover an even brighter future," Shen said.

Officials have also said the elimination of presidential term limits is aimed only at bringing the office of the president in line with Xi's other positions atop the Communist Party and the Central Military Commission, which do not impose term limits.

Xi has built his presidency on a promise to "rejuvenate" China and put the country back at the center of the world. Now he must deliver, experts said.

"Everyone expects that this will make Xi Jinping a stronger, more decisive leader, but it's also possible that he will need to justify this change by maintaining his popularity," said Mary Gallagher, director of the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan.

"That doesn't bode well for difficult reforms ahead: Will the [Communist Party] be able to raise the retirement age? Enact a property tax?" she continued.

"A second-term president with nothing to lose might have been in a better position to enact these changes and accept the blame before stepping down."

While some scholars questioned the wisdom of the move, others said they saw value in sending the message that Xi would be setting policy for many years to come.

"In fact, the more Xi Jinping's position is consolidated and the longer his governing time is to last, the more secure it is for the continuity of the policies," said Liu Jiangyong, a professor at Renmin University's School of International Relations.

Tsang, of SOAS, said the constitutional change signaled a worrying trend: the elimination of dissenting views in policymaking.

"If Xi is right, he will be more effective in getting his policies implemented," Tsang continued. "But if Xi gets it wrong on any major policy matter, God (or Marx) help China, for there will be no one else who can."

"Term limits, avoidance of a cult of personality, and the end of routine political purges -- all of these were part of China's reform-era leaders' efforts to steer the nation out of the chaos and instability of the Maoist era," said Carl Minzner, a professor of law at Fordham University in New York and author of a new book on Xi's authoritarianism. "As these start to fall like dominoes, the operative question is: What could go next?"

Information for this article was contributed by Emily Rauhala, Amber Ziye Wang, Shirley Feng, Luna Lin and Yang Liu of The Washington Post; by Christopher Bodeen, Fu Ting and Shanshan Wang of The Associated Press; and by Chris Buckley and Steven Lee Myers of The New York Times.

A Section on 03/12/2018