ROME -- The music swelled, heavenly clouds began to fade and impossibly bright rays of lights began to cut through the theater. And then it stopped.

The spectacle's artistic director, Marco Balich, waited patiently. "What's going on?" he asked his creative producer.

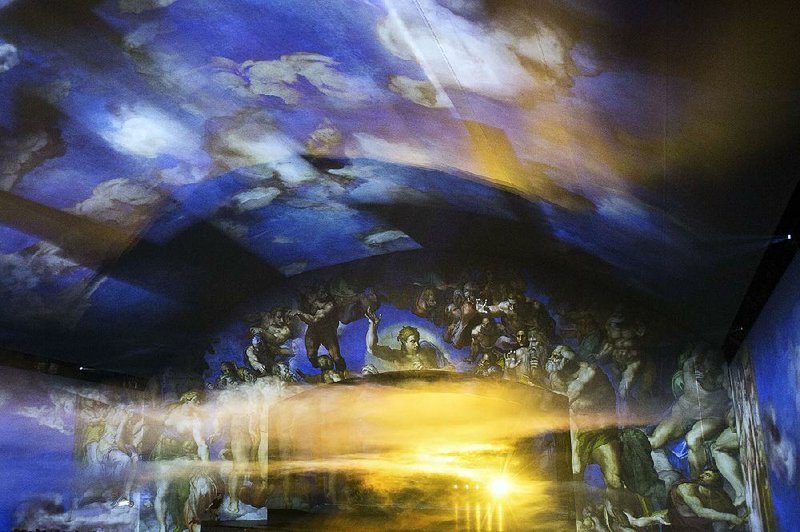

"Power outage," responded the producer, Stefania Opipari. Later, she said that it was the first time all of the lasers, projectors and special effects of the multimedia production, Universal Judgment: Michelangelo and the Secrets of the Sistine Chapel, had been turned on at the same time. "It was a minor problem," she said. "We fixed it."

The debut of Universal Judgment was just over a week away, but if Balich, who is also the show's producer, was nervous, you'd never have known it.

He has a lot at stake on the production, which debuted Thursday. He has booked this capital's former symphony hall for at least a year. If it is successful, it would become Rome's first permanent theatrical production along the lines of Broadway in New York or the West End in London.

The Vatican has approved the project, on the condition that it would respect the artistic, religious and spiritual values that the Sistine Chapel embodies. Balich has to live up to that promise.

The Vatican Museums, which house the Sistine Chapel, provided high-definition digital reproductions of the frescoes in the hall at a reduced rate because they acknowledged the project's educational value. Museum experts consulted on historical and other questions. "This I liked, because it showed that they were serious," said Barbara Jatta, director of the Vatican Museums.

At the same time, Balich had to create something that will enchant Romans (who, surrounded by beauty, are reluctant to pay for it), tourists, cardinals and teenagers. He has got a private investment of $11 million and years of planning riding on it.

Balich also has to convince Italy's traditionally skeptical art conservators that he is not out to circumvent visits to the real chapel with a glitzy concoction that includes theater, ballet and many, many bells and whistles. "Italy has all these very conservative art critics, and they are against the idea of 'spettacolarizzazione,'" he said, using an Italian expression for putting on a big show.

"They hate that word; I love that word," Balich said. "When they say, 'Oh but we don't want to make a Disney kind of thing,' I say, 'But Disney was a genius -- what's wrong with that?'"

One of Italy's most respected cultural critics, Tomaso Montanari, described the over-the-top effects as "visual Viagra," wondering outright whether they were "more of a mirror of the present than a means to better understand the past."

"It's like all the buzz over virtual sex -- but what's wrong with the real thing?" said Montanari, who teaches art history at the University of Naples. "It's based on the notion that Michelangelo no longer speaks to modern sensibilities."

The Vatican followed the process step by step. While it did not interfere with the creative aspects of the production, Vatican officials kept tabs to make sure that the show's content and references were historically accurate and did not stray too far from the righteous path.

"We have been very, very, very obedient and careful and precise because that was our insurance policy. To have them on board was to be sure that everything will be exact and appropriate," Balich said of the Vatican's support during a rehearsal break.

"Obviously this comes with a price," he said, conceding that if he had his way, he would have "probably added more special effects."

The musical merger between the Vatican Museums, keepers of one of the greatest artistic troves of humanity, and Balich, best known as the designer of over-the-top spectacles -- among them the closing ceremony of the Sochi Olympics in 2014, both ceremonies for the Turin Games in 2006 and the 550th anniversary celebration of Kazakhstan -- was not an obvious match.

Pope Francis is known for his casual, avuncular style. The Vatican, though, is not accustomed to sharing top billing with the likes of Sting, who wrote the main theme of the show.

But Balich believes that his Olympics experience played in his favor. "The Vatican understood that our work is always celebrating values," he said. "In the Olympics, you don't go in with a cynical approach."

Balich said he wanted "to put the grammar of the big Olympics at the service of the Sistine Chapel, which is one of the milestones of humanity." The Vatican, he added, understood "that we were well intentioned."

It took some time. Balich first began discussing his idea with the Vatican in 2015. He laughed when it was pointed out that it took Michelangelo four years to paint the Sistine Chapel's ceiling, between 1508 and 1512, about the same time as it took to complete the project.

The Roman Catholic Church has a long history of embracing technological advancements, however. The Vatican was at the forefront of astronomical research for centuries. Pope Pius XI championed Guglielmo Marconi to establish Vatican Radio in 1931. Several popes were intrigued by photography in its nascent years, and Leo XIII was the first pope to be filmed giving a blessing in 1896.

Leo XIII "understood that through the camera, he was blessing the audience. A pope who was confined reached the world through the new medium," said the Rev. Dario Edoardo Vigano, the prelate responsible for the Vatican's communications division, which approved Balich's project. With the show, the Vatican is embracing a language that appeals to young generations, Vigano said.

The 60-minute performance does not seek to evangelize, Balich said, adding, "The Vatican never suggested it should." Instead, the production is more like a meditation on Michelangelo's relationship with his creation, and on creation in general. "It's about capturing the spirit between the artist and his masterpiece," said Lulu Helbek, co-director of the show.

"We can't do anything bigger than Michelangelo -- it's like committing a sin to suggest that," said Fotis Nikolaou, the show's choreographer, and another Olympics alumnus. "We're [working] with this masterpiece in the new forms of art, video, dance, theater. It's like saying thank you to a masterpiece like the Sistine Chapel."

As most sightseers to the real Sistine Chapel know, the visit isn't always edifying. The hall, though large, is almost always packed, and even though silence is mandatory visiting can be noisy. Ensuring that visitors have a positive experience there "is constantly on my mind," said Jatta, the Vatican director -- and a problem that still has to be resolved.

Last week, Jatta saw a rehearsal of Universal Judgment and gave it a thumbs up. "It's a delicate way to tell a beautiful story of faith, art and history," she said. "And it's a way of communicating the Sistine Chapel in a way that many generations can understand."

Asked whether she thought it could replace visiting the real thing, she blinked.

"No, sorry," she said, and smiled.

Religion on 03/17/2018