SAN FRANCISCO -- The contemporary Internet was built on a bargain: Show us who you really are, and the digital world will be free to search or share that information.

People detailed their interests and obsessions on Facebook and Google, generating a river of data that could be collected and harnessed for advertising. The companies became wealthy. Users seemed happy. Privacy was deemed obsolete.

Now, the consumer surveillance model underlying Facebook and Google's free services is under siege from users, regulators and legislators on both sides of the Atlantic. It amounts to a crisis for an Internet industry that up until now had taken a reactive approach to problems like the spread of fraudulent news and misuse of personal data.

The recent revelation that Cambridge Analytica, a voter profiling company that had worked with Donald Trump's presidential campaign, harvested data from 50 million Facebook users raised the current uproar, even if the origins lie as far back as the 2016 election.

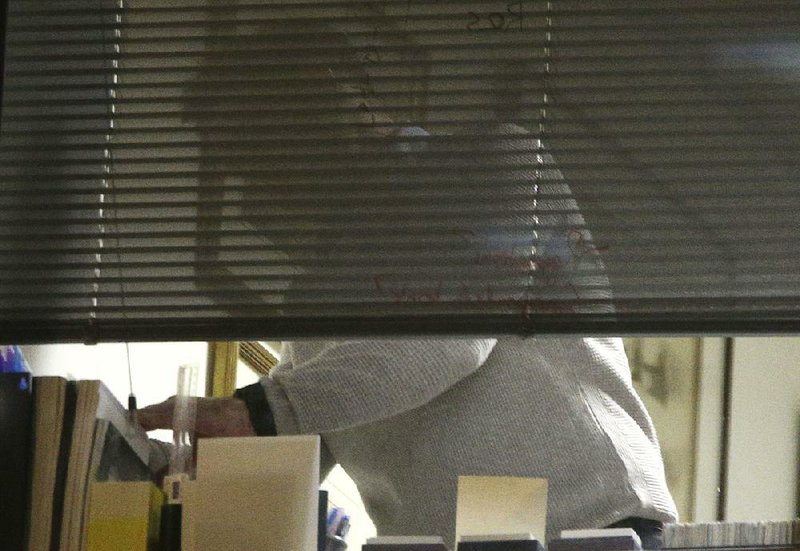

On Saturday, Britain's information regulator said it was assessing evidence gathered from a Friday raid on Cambridge Analytica's office.

More than a dozen investigators from the information commissioner's office entered the company's central London office late Friday, shortly after a High Court judge granted a warrant. The investigators were seen leaving the premises early Saturday after spending about seven hours searching the office.

The regulator said it will "consider the evidence before deciding the next steps and coming to any conclusions."

"This is one part of a larger investigation by the ICO into the use of personal data and analytics by political campaigns, parties, social media companies and other commercial actors," it said.

The data firm suspended its chief executive Alexander Nix last week after Britain's Channel 4 News broadcast footage that appeared to show Nix suggesting tactics like entrapment or bribery that his company could use to discredit politicians. The footage also showed Nix saying Cambridge Analytica played a major role in securing Trump's victory in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Cambridge Analytica's acting chief executive, Alexander Tayler, said Friday that he was sorry that SCL Elections, an affiliate of his company, "licensed Facebook data and derivatives from a research company [Global Science Research] that had not received consent from most respondents" in 2014.

"The company believed that the data had been obtained in line with Facebook's terms of service and data protection laws," Tayler said.

His statement said the data was deleted in 2015 at Facebook's request and denied that any of the Facebook data that Cambridge Analytica obtained was used in the work it did on the 2016 U.S. election.

IDEAS FOR CHANGE

There has been a good deal of debate about more restrictive futures for Facebook and Google. At the furthest extreme, some dream of the companies becoming public utilities. More benign business models that depend less on ads and more on subscriptions have been proposed, although it's unclear why either company would abandon something that has made them so prosperous.

Congress might pass targeted legislation to restrict consumer data use in specific sectors, such as a Senate bill that would require increased transparency in online political advertising, said Daniel Weitzner, director of the Internet Policy Research Initiative at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

There are other avenues still, said Jascha Kaykas-Wolff, the chief marketing officer of Mozilla, the nonprofit organization behind the popular Firefox browser, including advertisers and large tech platforms collecting vastly less user data and still effectively customizing ads to consumers.

"They are just collecting all the data to try to find magic growth algorithms," Kaykas-Wolff said of online marketers. Last week, Mozilla halted its ads on Facebook, saying the social network's default privacy settings allowed access to too much data.

The greatest likelihood is that the Internet companies, frightened by the tumult, will accept a few more rules and work a little harder for transparency. And there will be hearings on Capitol Hill.

The next chapter is also set to play out not in Washington but in Europe, where regulators have already cracked down on privacy violations and are examining the role of data in online advertising.

The Cambridge Analytica case, said Vera Jourova, the European Union commissioner for justice, consumers and gender equality, was not just a breach of private data. "This is much more serious, because here we witness the threat to democracy, to democratic plurality," she said.

Although many people had a general understanding that free online services used their personal details to customize the ads they saw, the latest controversy starkly exposed the machinery.

Consumers' seemingly benign activities -- their likes -- could be used to covertly categorize and influence their behavior. And not just by unknown third parties. Facebook itself has worked directly with presidential campaigns on ad targeting, describing its services in a company case study as "influencing voters."

"People are upset that their data may have been used to secretly influence 2016 voters," said Alessandro Acquisti, a professor of information technology and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University. "If your personal information can help sway elections, which affects everyone's life and societal well-being, maybe privacy does matter after all."

In interviews, Facebook's chief executive officer, Mark Zuckerberg, and Sheryl Sandberg, chief operating officer, seemed to accept the possibility of increased privacy regulation, something that would have been unlikely only a few months ago. But some trade group executives also warned that any attempt to curb the use of consumer data would put the business model of the ad-supported Internet at risk.

"You're undermining a fundamental concept in advertising: reaching consumers who are interested in a particular product," said Dean Garfield, chief executive of the Information Technology Industry Council, a trade group in Washington whose members include Amazon, Facebook, Google and Twitter.

SUSPICION IN EUROPE

If suspicion of Facebook and Google is a relatively new feeling in the United States, it has been embedded in Europe for historical and cultural reasons that date back to the Nazi Gestapo, the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe and the Cold War.

"We're at an inflection point, when the great wave of optimism about tech is giving way to growing alarm," said Heather Grabbe, director of the Open Society European Policy Institute. "This is the moment when Europeans turn to the state for protection and answers and are less likely than Americans to rely on the market to sort out imbalances."

In May, the European Union is instituting a comprehensive new privacy law, called the General Data Protection Regulation. The new rules treat personal data as proprietary, owned by an individual, and any use of that data must be accompanied by permission -- opting in rather than opting out -- after receiving a request written in clear language, not legalese.

Melanie Voin, a spokesman for the European Commission, said the protection rules will have more teeth than the current 1995 directive. For example, a company experiencing a data breach involving individuals must notify the data protection authority within 72 hours and would be subject to fines of up to 20 million euros (roughly $25 million) or 4 percent of its annual revenue.

In a January speech in Brussels, Facebook's Sandberg said, "We know we can't just meet the [General Data Protection Regulation], but we need to do even more." Google declined to comment.

The United States does not have a consumer privacy law like the General Data Protection Regulation. But after years of pushing for similar legislation, privacy groups said recent events were giving them new momentum -- and they were looking to Europe for inspiration.

"With the new European law, regulators for the first time have real enforcement tools," said Jeffrey Chester, the executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy, a nonprofit group in Washington.

"We now have a way to hold these companies accountable."

Information for this article was contributed by David Streitfeld, Natasha Singer and Steven Erlanger of The New York Times; and by Sylvia Hui of The Associated Press.

A Section on 03/25/2018