Look at all your material things; your pictures and dishes and furniture; your tools and clothes and toys.

What do they say about you, about the time in which you live, about the life you lead?

A lot, of course.

Years from now people will look at the things we have left behind, the things we used in our everyday lives, to learn about us.

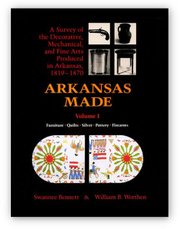

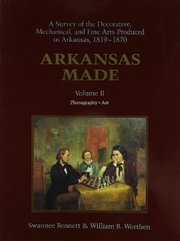

In the early 1990s, two books were published by the University of Arkansas Press that gathered material items made by people in Arkansas over 21 years in the 19th century. Written by Swannee Bennett and William B. Worthen of the Arkansas Territorial Restoration, now known as Historic Arkansas Museum, the two volumes celebrated goods made by Arkansas artisans and artists.

. . .

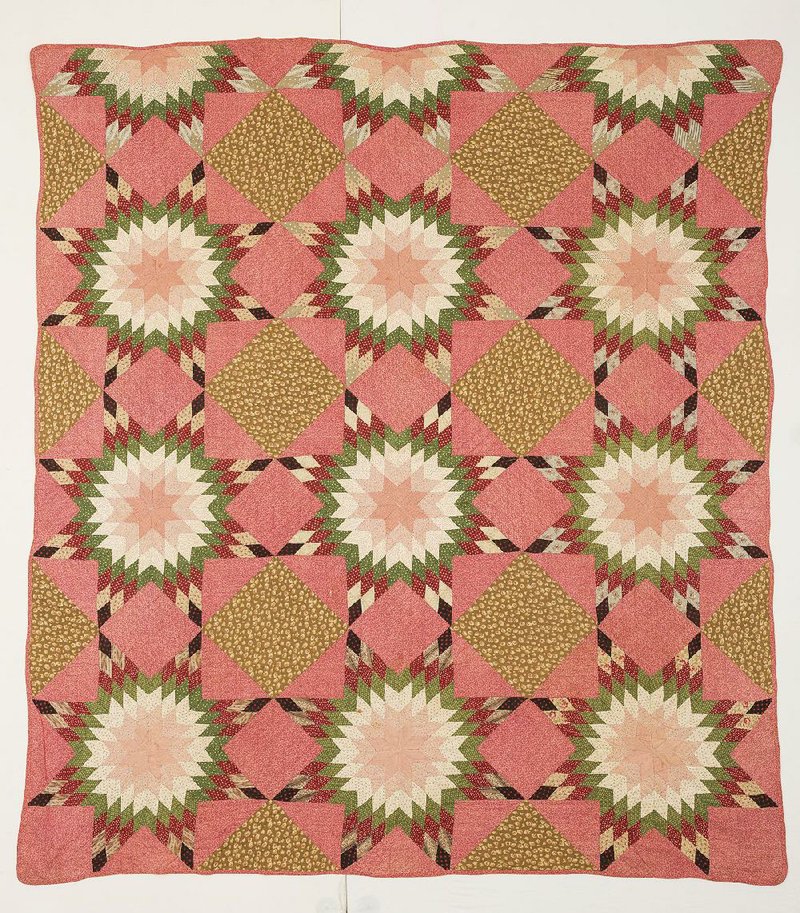

Arkansas Made, A Survey of the Decorative, Mechanical and Fine Arts Produced in Arkansas 1819-1870 Volume I was published in 1990 and focused on furniture, quilts, silver, pottery and firearms. Volume II from 1991 concentrated on photography and art.

The books were the result of a sort of treasure hunt that took researchers across the state and beyond, says Bennett, the museum's director and chief curator.

"We started doing the field work in 1976," he says. "We traveled everywhere. I was in Tennessee, Mississippi, New York, Alabama, and every county in Arkansas."

The result was an ambitious pair of books, each with about 200 photographs, that detail the state's material culture from that time and the items that were made here and used by people who lived here.

"A place's reputation is often based on its material culture," says Worthen, the retired former director of the museum. "We realized no one had done any serious research into the artistic legacy and material culture of Arkansas. If you don't have information about it, you tend to think it's not worth much."

Included in the books are things like a cherry and tulip poplar bureau, circa 1860, from Greene County made by Lawrence Thompson; a rare jug, also circa 1860, made by the Bird family of potters in Dallas County; a painting from 1822 that was sketched in Arkansas by John James Audubon and that appeared in his Birds of America; Caplock "Schuetzen" rifles made by Little Rock gunsmith Edward Linzel between 1870-80; Karl Bodmer's spare, beautiful 1833 watercolor Confluence of the Arkansaw and Mississippi River; artist Seth Eastman's 1848 sketches showing the earliest images of Helena and many other gems.

"We were very pleased with the creative legacy of early Arkansas," Worthen says. "It showed that Arkansas was in the mainstream of the artisan tradition. We had a lot of people who came to Arkansas just to be able to make things and sell them."

Tim Nutt, director of the historical research center at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, came across the Arkansas Made books as an undergraduate at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway.

"It's a comprehensive resource for all of the arts that have come out of Arkansas," he says. "It touched on every aspect of the arts, from fine art to decorative art to furniture. Nothing like that had ever been produced before. It was a wonder to see those two books published."

Now Bennett, Worthen and researchers with the museum have assembled an expanded version of the first two books that reaches into 1950 and also looks back to the earliest people of Arkansas and the material items they left behind.

UA Press is again the publisher, and while there's no firm publication there are hopes to have it out by next fall.

"We are excited to publish these new volumes which showcase the abundance of artistic talent and creative spirit present in Arkansas from 1819-1950," says UA Press director Mike Bieker. "The first two volumes in the series were greatly appreciated by our readers, and we feel confident the new volumes will be equally treasured."

. . .

There's a quote from artist and art critic John Ruskin that Bennett loves.

"Great nations write their autobiographies in three manuscripts -- the book of their deeds, the book of their words and the book of their art."

"That is so true," says Bennett, who worked at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia before returning to the Historic Arkansas Museum in the early '80s. "Objects can tell us a lot about the attitudes, the assumptions, socio-economic development of an area and one's place within the community."

And also about the people who made the objects.

"You had to have cabinet makers, you had to have brick masons, you had to have blacksmiths," Bennett says. "All of those things that cause industry to work and to survive in what was slowly developing as this frontier that was moving inexorably west as part of manifest destiny."

A chapter in the expanded volumes by State Archaeologist Ann Early covers American Indians in Arkansas, which weren't a part of the first two books.

"We wanted to make sure that the first Arkansans, the first people of Arkansas, were represented," Bennett says.

"My job was to provide a summary and review of objects made by native people in Arkansas over the millennia," Early says.

Her chapter includes "objects of special technical, aesthetic qualities that were good examples of things made in Arkansas by native people," she says. Some of the items date back to the end of the ice age, 13,500 years ago.

The most recent artifacts included are painted animal skins housed at a museum in France that are believed to have been made in the 1700s by Quapaw Indians in eastern Arkansas.

"They are not signed, and we don't have eyewitness testimony to their manufacture," Early says, "but the imagery and the organization of the painted skins indicate activities and events in Arkansas, and we believe they are connected to the Quapaws."

There also is a new chapter by Tommy Jameson and Joan Gould on vernacular architecture.

"It's architecture of the people, an amalgam of styles," Bennett says.

. . .

As early as the late 1870s, artisans such as cabinet makers, silversmiths and gunsmiths were being eased aside by the growing industrialization of America, Bennett says. Furniture, guns and other goods were being made elsewhere in mass quantities and shipped here.

Artists, though, continued applying paint to canvas.

In compiling the new expanded versions, Bennett says, the number of visual artists working in Arkansas was the biggest surprise.

Working with Little Rock art appraiser and adviser Jennifer Carman, he says, they found "a total of 1,100 people we would identify as professional artists or cottage artists, self-taught. Gosh, it's just an unbelievable group of painters who were here."

Missouri's Thomas Hart Benton frequently painted in the state, Bennett says, and Eureka Springs artists Louis and Elsie Freund are also represented in the new edition.

Over the years, Historic Arkansas Museum has become sort of the state's attic, the place where neat, old Arkansas stuff gets stored.

"One of the nice things about the last books was that it brought some things out of the woodwork," Worthen says. "People said, 'Well, I have something that could have been in that book,' and we'd say, 'May we see it?' We're the primary repository for the state for this kind of thing. Nobody has anything that compares to the breadth and depth of Historic Arkansas Museum's Arkansas Made."

For Nutt, the expanded editions already have a good start.

"They are building from a great foundation. Anything they build on from the original two Arkansas Made books will be a great work. I'm glad it's being updated, and I'm looking forward to seeing what other artwork and furniture is presented in these new volumes."

The work will continue, Worthen adds.

"The Arkansas Made team at the museum is incredible ... we really think this is going to be a beautiful publication. We've put a lot of energy into getting these books out, and that energy will be allocated to other things for a while, but we will always have an interest in Arkansas Made, and we will always collect Arkansas creativity. It's our history, and we are completely committed to doing this."

Style on 11/04/2018