Robin Robertson is a Scot who has supported himself by working as an editor. He has worked with John Banville and J.M. Coetzee. Mainly he's a poet who has published six collections in the past 20 years.

That puts you off. Probably.

Because there is no time for poetry, which infuriates and makes you feel ... well, dumb. You want something more direct. A jolt, a parsable thrill. Zombies walking, not whatever elliptical thing that can't quite be said.

But listen. You want to look at this book.

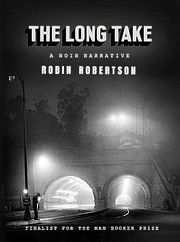

The Long Take. Knopf. $27. Finalist for the Man Booker Prize.

You want to sit with it awhile, long enough to feel its lift and tumble, to get a sense of its rhythm.

The way to watch Shakespeare is to relax into it, like into a bath that first feels too warm. You will acclimate. This book is not difficult; it just presents in syncopation and the discrete apprehended image. You give it a chance, you will pull sense from the jangle. You will get the story. Have faith in yourself.

Read this poetry.

There are other books to which it might be compared. Those of James Ellroy, his Los Angeles-set noirs. This is a story about a soldier back from the war but never home. His nerves ruined. His heart broken.

In 1946, he arrives in New York.

And there it was: the swell

and glitter of it like a standing wave --

the fabled, smoking ruin, the new towers rising

through the blue,

the ranked array of ivory and gold, the glint,

the glamour of buried light

as the world turned round it

very slowly

this autumn morning, all amazed.

A fresh veteran, raw and unfit for civilization. ("How you gonna keep them down on the farm?") Walker, he's called. He's Canadian, from Nova Scotia. He can't go back after the things he has seen, though there was a girl.

Stoic, he's a worker. He finds a foothold. He hangs on.

Spurred by a chance meeting with Robert Siodmak, the German film director who made Hollywood noirs like The Killers, Walker crosses the country, east to west, a kind of pioneer. He ends up in the Los Angeles office of Police Chief William H. Parker and Mickey Cohen. It is a beautiful, provisional place.

He finds a home in Bunker Hill, the now-leveled downtown neighborhood of once-grand Victorian-era homes converted into cheap boarding houses. (I have to believe Robertson has seen Kent McKenzie's 1961 film The Exiles, about young American Indians recently moved from the reservation to Bunker Hill.) He finds a job writing for a newspaper. He finds a friend, a scrappy black man named Billy Idaho.

He finds colleagues and notices ambitious racist Pike, in constant shark-like motion. Jittery and ravenous. Eating a sandwich "like he had something against it."

He finds men like himself, more or less shattered. Glassface, tortured by Nazis trying to make him talk. Battalions of war-ruined men, drinking, sleeping in the streets. Unequipped.

Walker likes to read. He likes the movies. He likes jazz. He walks. He swims in the ocean, the Pacific:

Warmer, in February than the Atlantic

ever is. The smell of it.

It was funny: none of his people could swim.

He learnt in England

those years before the landings,

and loved it now.

Walker likes cities too. He studies them. He understands how they die.

He has success, so his newspaper sends him north to battle-smoked San Francisco to write about skid row.

Here and there the historical facts press forward. Another German, Walter Friedlander, a lawyer who escaped the Nazis to become a professor at Berkeley, turns up in a cameo, saying of the noir film for which he and Walker share enthusiasm: "At last! German Expressionism meets the American Dream!"

He returns to find Los Angeles devouring itself. Bulldozers and cranes, the real estate interest remaking the city, smoothing out its wrinkles and lumps. Redevelopment. The Angels Flight funicular is still there, a minor tourist attraction.

And in the final third of the book -- which is a novel, as well as an epic poem -- we begin to learn something of what Walker did in the war. About what he has been carrying around with him. About the Hitlerjugend, Kurt Meyer and the 12th SS Panzer Division. What they did to the North Nova Scotia Highlanders.

You should read this.

Not because it will improve you in any real sense, at least not any more than we are ever improved by the books we read or the movies we see, but because you will like it. It will get into your system and change you in some small way. Maybe it will make you more alert to the way the world manifests itself to a man like Walker. Maybe you will at least feel like you know a little of how it must be to be a soldier who cannot go home.

You should read this.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 11/25/2018