For me, the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival signals the beginning of the best part of the movie year.

From here until the end of 2018, I expect to be in full-on movie critic mode. I'm planning to be around the 27th annual Hot Springs festival this week (though we'll miss the second weekend of the festival because of a commitment to the Savannah Film Festival), and for the next couple of months I'll catch up on notable films missed this year and plowing through end-of-the-year "for your consideration" screeners.

I've seen a fair number of the 127 films that will screen in Hot Springs. Of the full-length features I can wholeheartedly recommend Chris Quinn's Eating Animals, Kate Novack's fashion icon profile The Gospel According to Andre, Julie Cohen and Betsy West's RGB, Matt Tyrnauer's Studio 54, Michael del Monte's Transformer (about a transsexual woman who competes in weightlifting competitions), Michael Dweck's poignant stock car story The Last Race and Morgan Neville's Won't You Be My Neighbor?.

(The critical and commercial success of RGB and Won't You Be My Neighbor? might lead us to believe this is The Year of the Documentary. But we could have said that about every year since 2002, when Michael Moore's Bowling for Columbine became a box-office sensation.)

I'm intrigued by Sally Rubin and Ashley York's Hillbilly, the film that opens the festival this evening (it will screen in the Crystal Ballroom of the Arlington Resort Hotel & Spa; check hsdff.com for tickets and more information) and by Dana Adams Shapiro's Daughters of the Sexual Revolution: The Untold Story of the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders, which will close the festival.

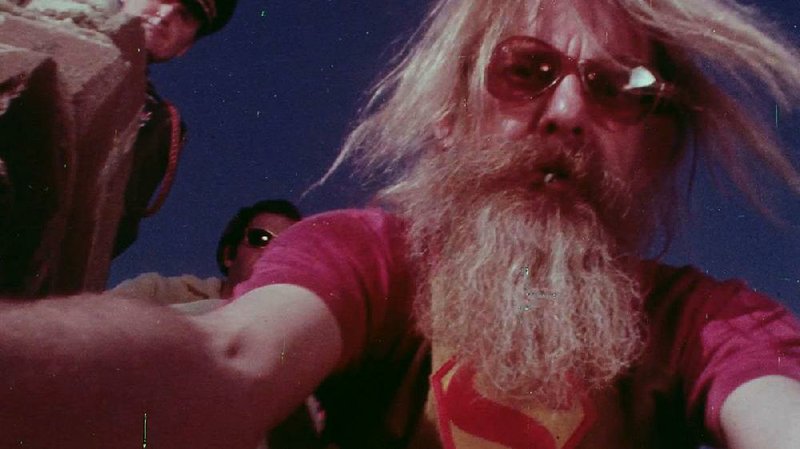

In between, see Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi's rock-climbing movie Free Solo; Amy Scott's cautionary tale about '70s director Hal Ashby, Hal; and Little Rock filmmaker Mark Thiedeman's work-in-progress Kevin, about a young skateboarder who chooses to live life on his own terms, becoming a source of inspiration for the friends and family around him.

Venerable Arkansas filmmaker Larry Foley has two shorts in the festival, the 44-minute Make Room for Pie, which shadows Little Rock-based food writer Kat Robinson on her travels around the state, and the 14-minute Frank Broyles, Arkansas Legend. Gospel of Eureka compares and contrasts the performances of Eureka Springs' drag community with the city's long-running Passion Play.

But what always happens is that I stumble into something unexpected. It's wonderful to drift into a film with no expectations. Sometimes I drift right back out, but every festival yields its surprises.

While -- thanks largely to the Hot Springs festival -- Arkansans might be better educated about the entertainment possibilities of documentaries than the general public, there are quite a few of us who still equate the word "documentary" with a certain kind of didactic broadside or eat-your-vegetables moralizing. There is still the idea that documentary watching is a serious pursuit, undertaken for purposes of self-improvement. When some people think about documentary films, the image that comes to mind is grainy black-and-white footage of Ukrainian peasants standing on line for rations of black bread and vodka, or perhaps red-jawed lions running down gazelle in the Serengeti.

We should know better. Every December it's easy to find 20 or 30 nonfiction films that deserve to be considered among the year's best of any sort. And I don't necessarily think consumers should use documentaries differently from other features -- the alert moviegoer understands that every movie is selling something, be it a placed product or the idea that we create the world as we apprehend it. A documentary is a kind of journalism, and therefore it must either conform to established notions of fairness and accuracy or suffer the poor opinions of ethicists. We ought to understand that documentaries are generally made to corroborate an opinion, that they are arguments made by people who have a point of view. While we may not agree with that point of view, we probably shouldn't expect partisans to be balanced.

There's a trick to this. If an argumentative documentarian goes too far -- if he cooks evidence or ignores the facts that don't fit in with his pet hypothesis -- he runs the risk of being discredited. This is why someone like Michael Moore (or Dinesh D'Souza) becomes such a polarizing figure. Moore not only makes himself the center of his films (an appropriate strategy for someone looking to draw an audience) but he occasionally overplays his hand.

It's not just what you have to say, it's how you say it. There are no doubt times when a documentarian who aspires to reach a reasonable audience must make difficult choices. My preference is for documentaries that practice best journalistic practices, but the artist's only prerequisite is to connect. Propaganda can entertain; we just ought to be aware that it is propaganda.

And there's nothing wrong with seeing a movie just because it makes you feel good. That's why I've got Don Hardy Jr. and Dana Nachman's Pick of the Litter -- which follows a litter of puppies as they train to become guide dogs -- on my must-see list.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

www.blooddirtangels.com

MovieStyle on 10/19/2018