Let's talk dubs.

A small item in the Oct. 15, 1918, Arkansas Gazette captured a vivid scene from the streets of the capital city:

Fire which damaged two one-story dwellings at Ninth Street and Broadway early yesterday morning brought forth a hero for one brief minute, then made him into a dub again.

Cheerfully, the item reported that "Pete," a blind black man who played a big bass viol in a segregated orchestra, couldn't tell how far the fire might spread and so hastily made his way out of his building. In the street he let out a yell begging someone, anyone, "Save mah fiddle. Save mah fiddle."

Before the eyes of a hundred spectators, one brave bystander dashed into the burning building.

In a minute out he dashed with the precious bass viol under his arms. The big instrument obstructed his view as he ran across the street, his feet became entangled in a stretch of fire hose and down came hero, fiddle and all, with a loud bang.

Owned by the Bragg family estate, the buildings were not greatly damaged. But the instrument was a goner; and that would-be Good Samaritan fled as quickly as he could.

The Gazette is a trove of such vignettes, glimpses of everyday life that would be charmers were they not so often delivered in dialect that seems designed to mock the speakers. But it was the reporter's word "dub" that stopped me.

The headline used it, too: "A Hero for One Brief Minute, and Then a Dub Again." What did it mean?

Dub is an unincorporated community in Poinsett County. And we know people named Dub. The 2017 voters rolls list three people with that last name and two whose middle name is Dub. Remember Jefferson County Sheriff Walter C. "Dub" Brassell (1920-2000) and Pulaski and Perry counties prosecutor Wilbur "Dub" Bentley (1927-2007)?

Perhaps it's no coincidence that their first names begin with W. Imagine a young speller sounding out the letters, and Dub becomes a natural nickname. Someone, please, run ask Chief Justice William Howard "Dub" Arnold about that and report back.

Having lived in the age of dubbed, or copied recordings, as well as the age of voice dubbing -- replacing foreign speech with a translation -- cousins might call a boy who looks like his daddy "Dub."

We know it's an old word. Quaintly power-consolidating monarchs rewarded loyal followersby dubbing them Sir This or Sir That with a sword tap. But according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the noun joined the language in the middle of the 15th century as an artificial fly for fly fishing.

By the 16th century, Scots were calling stagnant pools "dubs."

By the end of the 1500s, "dub" was the sound of a beating drum, and then the sound of a blow, or of vigorous scrubbing in the bath.

The OED proceeds through other meanings until it reaches an Americanism that explains what the Gazette reporter was saying: "one who is inexperienced or unskillful at anything; a duffer, fool."

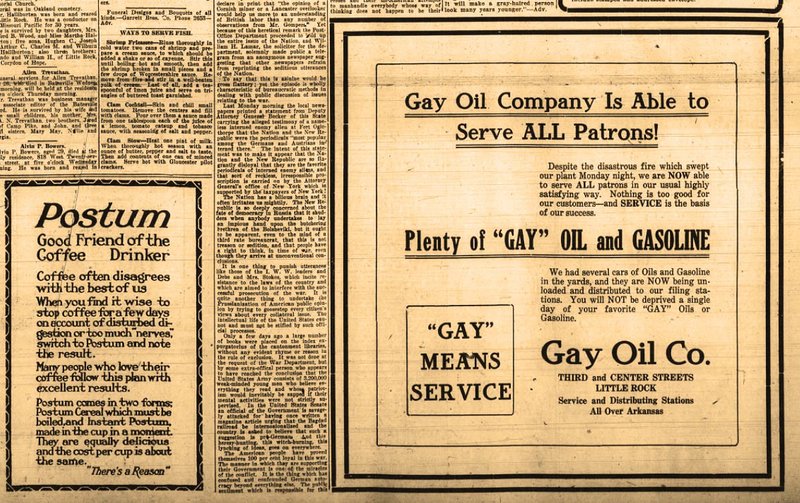

GAY OIL ON FIRE

Those long-ago Arkansans feel like neighbors -- until they go all racist on us or they don't want to pay for sewers or we notice they're still riding horses around town. Or they use some word the way they used it, a way that doesn't make sense to us.

An easy example is "gay." Even though my dictionary's definition still begins with "joyous and lively; merry; happy; lighthearted," the word has evolved since 1918.

And so the title "Gay Office Building" engraved on a facade at 300 S. Broadway in Little Rock might give ... I almost typed "might give us the giggles," but I should know better than to presume Dear Reader is as immature as I am.

The Gay Oil Co.'s two-story, brick, classical revival building is on the National Register of Historic Places, but in 1918 it didn't exist. Gay Oil had headquarters at Third and Center streets, and its storage tanks were near the Arkansas River at Ninth Street, beside tanks for the Rock Island Railroad.

On the night of Oct. 7, 1918, a Gay Oil delivery truck backfired. Its cylindrical tank had just been filled, and gas had run over the sides. The driver escaped an instant inferno; and no one else was hurt -- even though six tanks containing 15,000 gallons each, a 25,000-gallon tank of lubricating oil and several 20,000-gallon machine-oil tanks exploded.

Firemen from companies two and four somehow weren't decapitated by flying sheet iron.

The Arkansas Democrat reporter estimated that great blurts of burning oil launched skyward at least a dozen times, roaring 500 to 600 feet and evaporating as they fell. After about three hours, oil sluicing through a sewer pipe reached the river.

The surface of the water over a large area was immediately a mass of flame, at times the flame reaching a height of about 20 feet.

Fire crews brought that under control, somehow, after 30 minutes.

A black cloud covered the city. Damage was estimated at $70,000. The Hilliard Monument company nearby was destroyed, without insurance; but the Darrow Warehouse, filled with baled hay, escaped.

Two days later, Gay Oil ads in the Democrat and Gazette assured customers it was delivering "plenty of 'Gay' oil and gasoline" to its filling stations.

A highlight box in the ads proclaimed, "Gay means service."

BETTYS

One more odd word from 1918 before I let you go.

Although negotiations had begun to end the Great War, the U.S. Food Administration -- aka Herbert Hoover -- tightened its fist around sugar, butter, flour, meats.

On Oct. 14, 1918, the Gazette reported new rules for restaurants and boarding houses:

All bread must contain 20 percent flour substitutes; each person should be served no more than 2 ounces of such bread per meal; no bread could be served until the first course was on the table; no bread, toast or bacon could garnish a plate; only one kind of meat per person per meal; no more than 1/2 ounce of butter or American cheese per person per meal ...

No guest is permitted to have more than one teaspoonful of sugar, and that only when asked for.

Banquets were condemned, as were "unnecessary" suppers, teas and luncheons. The public should eat only three meals a day.

In this climate of austerity, marketers got creative, witness an ad from the American Cranberry Exchange, trademark: "Eatmor Cranberries."

Over a recipe for Cranberry Betty, an ad published 100 years ago Thursday declared, "Oh You Betty: A piquant, moreish, Hooverizing, come-hither pudding."

Hmm. "Betty" was then, at it is today, a baked dessert of sugared fruit and buttered crumbs. But something else is going on in this ad, a flirty allusion.

I have ransacked the Internet and the OED in vain for evidence that, in 1918, "Betty" was slang for a pretty girl. All I've found are observations that the name was a specifically American shortening of Elizabeth, dating from 1860, and it began rising in popularity about 1915.

But also during World War I, "betty" became slang for a man who did a woman's work, or a gay man.

I doubt they were selling cranberries as the gay berry, but who knows? Words have changed.

Email:

cstorey@arkansasonline.com

Style on 10/22/2018