Living legends die.

It is necessary, it cements them, it allows for apotheosis. Aretha Franklin is forever what you think she is.

And you are allowed to think differently, to have an opinion like the guy who wrote about her in National Review after she died on Aug. 17, who said, in an otherwise standard issue appreciative obituary that while she was definitely in the Top Five, he "might not rate her as the single greatest female vocalist of the rock era -- Kelly Clarkson and Linda Ronstadt come to mind as more versatile across musical genres and more varied in their emotional resonances."

A guy named Dan McLaughlin wrote that sentence. Fair enough, I guess. He caught Holy Hell across the social media platforms for it, which I suspect is the outcome he was hoping for, which is the only reason I have a problem with his brave decision not to engage in groupthink in the aftermath of Franklin's death. He can have whatever weird idea he wants to have, and on some occasion I might even find it interesting, but hot-taking in the immediate wake of a beloved pop icon's death seems a little too opportunistic and cheekishly self-advertising. (Don't they have editors at National Review?) But that's how the game is played. He won some eyeballs, and some eye rolls.

I don't get into making those kinds of lists. I don't know much about Clarkson. Someday I hope to write longishly and lovingly about Ronstadt's career from Heart Like a Wheel through Mad Love. Aretha Franklin is dead. We won't see her like again.

The moment for Franklin is past. Because most things seem to matter less now, and that's not Clarkson's fault. (Clarkson probably wishes her name had never come up in this context.) Singers can't matter as they once did. Pop music mostly comes down to track-and-hook product, a couple of Swedish guys making beats on a computer and auto-tuned toplines sung by celebrities. Some of whom, like Clarkson and Beyonce, have plenty of Old School chops. And it's not like there weren't empty-calorie teen idols in the '60s. OK. Times change.

That's not Katy Perry's fault.

What I might suggest is that what McLaughlin refers to as the "rock era" has been over for a couple of decades. Maybe longer. Maybe it ended with the death of Kurt Cobain or the ascension of the Backstreet Boys. Some people will blame hip-hop, but if you're actually looking for vital music these days you can't dismiss hip-hop. It's where the real artists are and the proof of that is how it upsets so many people who might have a brief for Foreigner or Foghat or The Human Beinz.

The music died, we're just waiting on the coroner to come back with an approximate time of death.

That's not Taylor Swift's fault.

. . .

Anyway, Aretha Franklin. There are things you need to hear -- the usual ones like "Respect," an Otis Redding song until she flipped it, but others that you might imagine are pretty cheesy too, like the 1985 duet with Annie Lennox of the Eurythmics, "Sisters Are Doin' It for Themselves." Franklin wasn't the first vocalist Lennox and her bandmate Dave Stewart thought of for the collaboration. They initially asked Tina Turner, seven years divorced from Ike and in the midst of her '80s renaissance, to sing on the track.

But Turner found the lyric too militant (!?) and somehow they got word that Franklin was willing. So they flew to Detroit. (In 1991, Lennox told Q magazine that it was a strange session because she didn't have an "immediate rapport" with Franklin: "Aretha struck me as rather shy, a bit sad, a bit lonely. She had an entourage which I thought a bit eccentric -- I wasn't used to it." ) It was worth it for the way Ree leans into her somewhat awkward solo lines in the second verse, "Mothers, daughters and their daughters too/Woman to woman" before Lennox and the gospel choir (the Charles Williams singers) join in: "We're singin' with you."

Lennox and Stewart wrote the song, which was released on Eurythmics' album Be Yourself Tonight and Franklin's Who's Zoomin' Who, which represented a commercial comeback for Franklin, who had gone nearly two years without a chart hit. The album produced three Billboard Top 10 hits, including the R&B No. 1 "Freeway of Love."

"Sisters," which of all the album's cuts seems to loom largest in the rearview mirror, in fact petered out at No. 66 on the R&B charts, No. 18 on the pop charts.

Which means nothing -- Bob Dylan didn't sell a lot of records in the '60s, and last week a guy called me to pooh-pooh the importance of The Band's Music From Big Pink because none of his buddies bought it when it was released in 1968. "We were listening to the Young Rascals," he said. (Which probably isn't technically true because the band dropped "young" from their name in 1967, but whatevs, dude.) Some things acquire significance over time and are fully appreciated only in retrospect, after we can measure how they reverberated and resonated.

So it doesn't really matter how many records Slim Whitman or Gene Austin sold -- Van Morrison matters more because of the psychic space he takes up in the heads of a bully generation that even in its senescenceretains the power to define what we consider important popular music.

While a certain threshold of visibility must be met to be taken under consideration -- an act must have at least attained the brand recognition of, say, the Velvet Underground -- popularity is no guarantee of relevance. Lots of people sell records and selling lots of records might even be held against an artist. Franklin sold more than 75 million records. Slim Whitman claimed to have sold more than 120 million. No one cares.

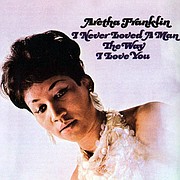

Who's Zoomin' Who? is not even an essential Aretha Franklin album; for those you have to go back to the string she released on Atlantic from March 1967 (I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You, which was remarkably the 10th album of her career) to January 1972 (Young, Gifted and Black). In that stretch she released eight LPs, all of which deserve a place in the library (or Spotify queue) of anyone with an earnest interest in the story of American popular song. Every American should be familiar with Aretha Franklin, just as they should be familiar with Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman.

But if you ask what the best Franklin recording from that period may be, I might say it's Oh Me, Oh My: Aretha Live in Philly, 1972, recorded at the convention of the National Association of Television & Radio Announcers. It wasn't released until 2007, and then only in a limited edition of 7,500 as part of Rhino's Hand Made imprint. (It has since become available for download and streaming, though if you want a physical CD you might have to pay more than $100 on eBay.)

This is Franklin at the peak of her Queen of Soul period, rushing through a 14-number, 56-minute set that touches on her greatest hits to date ("Respect," "Don't Play That Song"), four quick medleys ("I Never Loved a Man/I Say a Little Prayer;" "Day Dreaming/Think;" "Chain of Fools/See Saw," and a claim-staking coupling of "Bridge Over Troubled Water/We've Only Just Begun") along with a funky cover version of the Drifters' "Spanish Harlem," a smooth, sophisticated take on Burt Bacharach and Hal David's "This Girl's in Love With You," and a show-closing "Spirit in the Dark" that's more intense than any of the other versions of the Franklin-penned gospel barn burner. And, here and there, her assured and driving backing ensemble falls away to reveal Franklin's precise yet passionate piano.

If Verve Records hadn't copped the rubric for its jazz rosters' greatest hits compilations, you might have called this Aretha Franklin's Finest Hour.

. . .

There are singers who sing as well as Franklin.

It's hard to say what makes a great voice, though we might agree it's not just accuracy, the hitting and holding of notes. It comes down to taste, which is subjective and not worth arguing (though I think it is). There's something signature in the way each of us vibrates the air, something ineffably and unalterably ours, indivisible from our story. Aretha's story informs her mezzo-soprano, which writhes and shudders and strikes to the marrow if you let it.

Enough people have told Franklin's story in the past few weeks that it seems conventional to do so here. You can go to Google and see 406 Lucy Ave., the Memphis house she was born in, empty now but still standing, picturesque in its sloping poverty. It's a few blocks from STAX Records, now a museum.

Her father was a preacher -- famous in some circles for sermons he delivered in his "million-dollar voice." He moved the family to Buffalo, N.Y., then on to Detroit, where he took over New Bethel Baptist Church. Maybe you know about her complicated family situation -- her father's philandering and how her mother left (but stayed in touch) and died of a heart attack when Aretha was 10 years old. Mahalia Jackson baby-sat her. Gospel singer Clara Ward was her father's special friend and her first vocal mentor.

You know about her childhood gospel singing, how her father's church hosted Oscar Peterson and Nat "King" Cole and Art Tatum, who informed her piano playing, which is likely to forever remain underrated. The Rev. James Cleveland taught her gospel chords. She watched Duke Ellington's hands, she spent time with Dinah Washington, Della Reese, Ella Fitzgerald, Billy Eckstine, and Lionel Hampton. The kids in her neighborhood included Diana Ross and Smokey Robinson.

She had two children before she turned 15. She dropped out of high school in her sophomore year. By then, she was a gospel prodigy, recording for J.V.B. Records, a featured performer on the "gospel caravan" tours her father organized. You might know about the secular career that never really got started at Columbia Records.

You might know about her two bad marriages. You might know she was afraid to fly, and that she collected her money, in cash, before every gig. Sometimes she stuffed it in a pocketbook that she carried on stage and set down on top of her piano.

None of that makes her a better singer -- that's just the stuff that's indivisible from the way she made the air vibrate. You might prefer the way Clarkson makes the air vibrate. That's OK; this is America, where you can still think your own thoughts.

But my thoughts are that we are poorer for the way our music and culture have worked out, for the way we've made everything a game show reducible to winners and losers and page views and downloads and streams. We are driving out the mystery with our formulae and our machines that make the semi-tones snap to some pre-selected value on some grid.

I hate that we have made intelligence a cold thing to be despised in our artists, who are not to blame for the world they have to negotiate. Do not doubt that they have soul, it's just that we have lost our taste for real things. We need the carbonation and the sugar. We do not want our divas to be too sad.

And that is not Adele's or Lady Gaga's fault.

. . .

I think maybe the best thing ever written about Franklin is Nikki Giovanni's "Poem for Aretha" which I wish I could get away with reprinting in full. But the third stanza goes like this:

Nobody mentions how

it feels to become a freak

because you have talent

and how

no one gives a damn

how you feel

but only cares that Aretha Franklin is here like maybe that'll stop

chickens from frying

eggs from being laid

crackers from hating

But having Aretha here didn't stop none of that. And having her gone won't either.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 09/02/2018