"The men have failed ... It's time to call out the women."

-- Adolphine Fletcher Terry

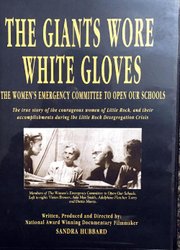

Sandra Hubbard's 1997 film The Giants Wore White Gloves: The Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools will screen at 2 p.m. Sunday at Ron Robinson Theater in downtown Little Rock's River Market. Hubbard -- who produced, wrote and directed -- will hold a question-and-answer session afterward.

It's part of the Clinton School Speaker Series that's co-sponsored by the Central Arkansas Library System's Butler Center, the theater, and the University of Arkansas Clinton School of Public Service. While all these events are free, you might want to reserve your seats by emailing publicprograms@clintonschool.uasys.edu or by calling (501) 683-5239.

The film, a little more than 40 minutes long, is a straightforward documentary that relies on the testimony of talking heads, archival footage and lots of still shots of newspaper stories. What's compelling is the story it tells.

Most people are vaguely aware of the circumstances that pushed Little Rock into the national headlines in 1957. When nine black students attempted to integrate Central High School in September 1957, Gov. Orval Faubus called in the Arkansas National Guard to block their entry. Later that month, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent in 1,200 members of the U.S. Army's 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell, Ky., and placed them in charge of the 10,000 National Guardsmen. The Little Rock Nine attended school that year.

The following September, Faubus invoked a recently passed state law to close four Little Rock schools pending the outcome of a public vote on whether to integrate them. On Sept. 16, 1958, the Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC) had its first meeting.

Initially organized by Adolphine Fletcher Terry, widow of U.S. Rep. David D. Terry (and sister of writer John Gould Fletcher, who won the 1939 Pulitzer Prize for poetry), and her friends Vivion Brewer (wife of Arkansas' U.S. Sen. Joe T. Robinson's nephew Joe Brewer), and Velma Powell (married to Central High School's vice principal J.O. Powell and a member of the interracial Arkansas Council on Human Relations), the WEC was a group of upper- and middle-class white women who worked to reopen Little Rock schools.

They first met on Sept. 16, 1958, at Terry's antebellum home, the Pike-Fletcher-Terry House at the corner of Eighth and Rock Streets, which now serves as the Arkansas Arts Center's community gallery. They immediately embarked on a campaign to keep the schools open but were rebuffed when, less than two weeks later, Little Rock citizens voted by a 3-1 margin to uphold Faubus' action.

The schools remained closed for the rest of the academic year.

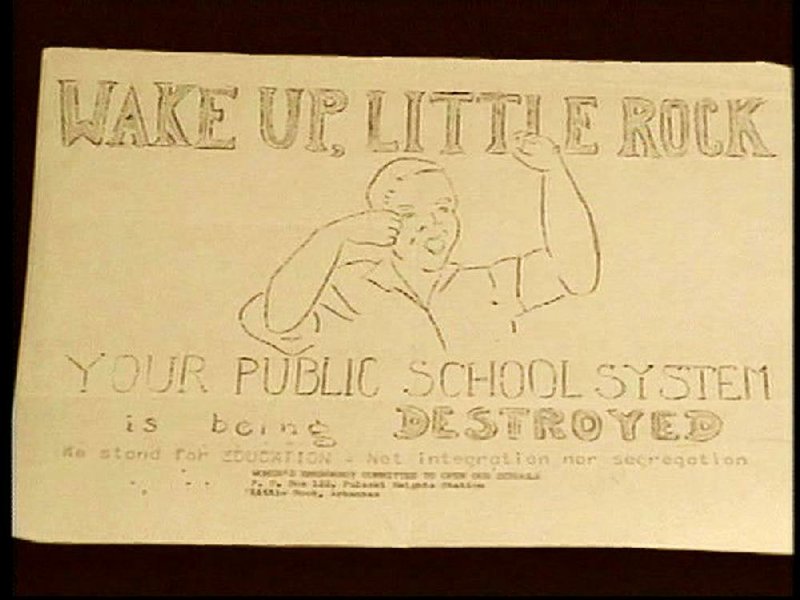

The WEC persisted despite hate mail and other social recriminations. The stigma of being labeled as an integrationist was strong enough that most of the group's membership remained secret, and when Brewer suggested collaborating with black women, the group decided to remain segregated. They adopted a public stance of standing "neither for integration, nor for segregation, but for education." They weren't about race mixing; they understood the closing of the schools as a disaster and wanted to retain the district's teachers.

In November 1958, five of six school board members resigned in frustration, and the WEC actively recruited "moderate" candidates who pledged to work to reopen the district's schools. After the elections, there were three segregationist school board members and three moderates.

On May 5, 1959, everything came to a head in a tempestuous school board meeting. Realizing that the hard-line members meant to fire teachers suspected of being sympathetic to desegregation, the three moderates walked out. With no quorum, they reasoned that the board couldn't fire the teachers. But the three remaining members acted anyway, firing 44 teachers.

This action galvanized the community, and the WEC went door-to-door to collect names for petitions, contacted voters, set up carpools to help take voters to the polls, and positioned themselves as poll watchers. When the votes came in, the three moderate members stayed on the board while the segregationist members were removed. Little Rock's high schools reopened in August 1959.

With the initial crisis over, the WEC members voted the organization out of existence in 1963. Still, many members continued to support education and equal opportunity individually and through other organizations, such as the Panel of American Women, whose members sought to change public opinion about desegregation through personal stories told by an integrated group of women. Through their work in the WEC, many women realized their potential political power and worked to empower others by providing voter education seminars and actively campaigning for candidates who supported public education.

Hubbard's film has the advantage of having been made while many of the members of WEC were still alive, and benefits from the firsthand testimony of Powell and others involved with the committee. It's a well-made film about a remarkable and courageous band of sisters.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

www.blooddirtangels.com

MovieStyle on 09/14/2018