For several years I belonged to an informal "Saturday Club" that met irregularly for lunch at Burge's in Little Rock's Heights neighborhood. It was a small gathering of writers, students, and fans of comics and animation art. One of the members was a quiet man who spoke only when he had something of substance to contribute. He displayed a good-natured sense of humor and a wide-ranging interest in comic-book artists, cartoons and film. His name was Carlton Hames Ware, and when he died on Sept. 5 at the age of 75, people far beyond that close-knit circle in Little Rock felt they had lost a friend and mentor.

I came to know Hames 40 years ago. In my first semester of law school, I was trying to find some distraction from the daily doses of mind-numbing legalese. A classmate who knew I had read and loved the Classics Illustrated series of comic-book literary adaptations as a kid told me he had found some in a flea market. He thought they might make a good break from Torts and Future Interests. The following weekend I drove to the place on the Old Benton Highway and was surprised to find old CI titles I had never seen.

This was during a period when organized comic-book collecting was in its early stages. Classics Illustrated comics, with their multiple print runs, were considered esoteric oddities. As I combed through the issues, I kept running across the neatly penned name "Hames Ware" or the initials "CHW" on the covers. My stack continued to grow taller, and finally the dealer said, "There are more than 100 Classics here; I'll let you have them all for $100." I knew that some of the titles had been out of print since the late 1940s, and I assumed I'd never see so many again, so I pulled out my checkbook.

The seller said, "These all came from the childhood collection of Hames Ware. He's an expert on comic-book artists, and he lives in Little Rock. You should give him a call. He's a really nice guy." He gave me the number, and I made the call. Hames was delighted to hear his Classics had gone to a good home, and he invited me to visit him to talk about the series. It was the beginning of a decadeslong friendship and -- more than law school -- a life-changing education.

What I didn't know about Hames when we met in 1978 was that he was already something of a legendary figure in the developing field of comics-art scholarship. From 1973 to 1976, he and co-editor Jerry Bails (known as the "Father of Comic Book Fandom") produced the four-volume Who's Who of American Comic Books, which meticulously documented the careers of Golden Age artists. Hames interviewed many veterans of the comics-art shops. His profiles of them, along with his colleague's, have formed the foundation for decades of serious research in the newly respectable field of comics studies. His notes and papers are now part of the collection of Columbia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

I was one of those who directly benefited from Hames' pioneering research. In 1993, with his encouragement, I began working on a manuscript that became Classics Illustrated: A Cultural History. I wanted to tell the stories of the artists, scriptwriters, and editors who created the series and made it an international graphic-novel prototype. From my conversations with Hames over the years, I had learned that he knew several CI contributors and was still in contact with them. In those pre-email days, he generously provided me with mailing addresses, connecting me with Lou Cameron and other artists whose correspondence and phone interviews formed the narrative core of my book.

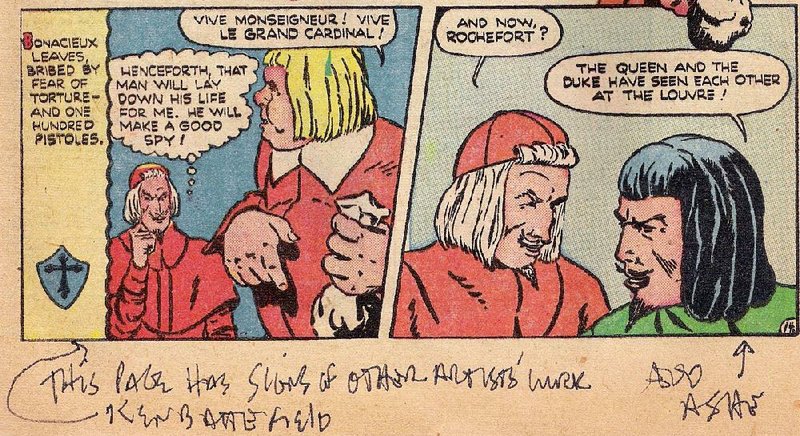

Hames introduced me to the history of the comic book, the comics-art shops of the 1940s and 1950s, and the styles that marked artists as different as Lillian Chestney, Matt Baker and Reed Crandall. He taught me the elements of comic-book illustration as an art form long before I had heard of Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics. In a series of tutorial sessions over a four-month period, Hames patiently went through issue after issue of Classics Illustrated with me, providing panel analyses. I still have my working copy of The Three Musketeers, which includes several notes by Hames. "This page [credited to Malcolm Kildale] has signs of other artists' work," he indicated in a bottom margin. To illustrate the point he wrote the name "Ken Battefield" with an arrow pointing to one figure and "Edd Ashe" beneath a neighboring panel.

Always sympathetic to the underpaid artists of the Golden Age and never dismissive of lesser illustrators, Hames always placed their work in the context of the assembly-line demands of the comic-book industry in its heyday. He made artists live again in anecdotes gathered from his years of interviews, and he punctuated his stories with the voices of the subjects, capturing, for example, the exuberance of Robert H. Webb, illustrator of the CI editions of Two Years Before the Mast and The Dark Frigate, who in retirement declared with satisfaction: "I used to draw boats, and now I build them!"

Hames went beyond mimicry in his impressions. He created a wide range of character voices that served him well in his parallel career as a professional voice artist. His work earned him a local and national reputation in the realm of radio and television commercials as well as film and radio productions. For a Central Arkansas Library System millage-increase campaign, Hames created a memorable Mark Twain who encouraged readers to vote. In a radio-play adaptation of Frankenstein, he supplied the haunted narration of a sea captain who rescued the tortured hero in the Arctic. Hames once told me that he could have made more money with his voice if he hadn't felt obliged to refuse projects that he found ethically compromised.

His younger sister, Lynne Clifton, remembers Hames as the creator of "elaborate fantasy games for our brother Allan and me," short plays, and even a "movie" made of "Polaroid stills viewed sequentially." He practiced artist identification at an early age with his sister: "Sometimes, Hames would invite me to look through a stack of comic books to try to find the artists' signatures, which were often cleverly hidden. I realized later that he was pretending that he didn't already know where they were. I think he was always very generous in that way, helping others feel they were achieving on their own."

I know exactly what she means. "You can spot these artists yourself now," he told me when we reached the last Classics Illustrated title. But I knew better. It was the gift of Hames Ware to every person he taught.

MovieStyle on 09/21/2018