Bryan Massey was 7 when he picked up his father's brand new screwdriver and hammer and started chiseling a portrait of his uncle out of a chunk of wood.

"I was always doing art. I always knew art was going to be part of my life in some form or fashion," says Massey, chairman of the art department at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway. "It was a relaxing thing back then. I didn't really think about it being a career."

Massey's first sculpture was a gift for his uncle, who was wounded during his second tour in Vietnam, but drawing was his favorite artistic outlet as a child growing up in rural Princeton, N.C.

"In 10th grade, I asked my mother if I could paint the Incredible Hulk on the wall in my bedroom. She said I could on one condition," he says. "I had to paint on the opposite wall a 6-foot figure of Jesus Christ, so I've got Jesus Christ on this wall and the Hulk on this wall -- talk about good and evil."

He didn't attempt sculpting again until after a chance encounter with a sculpture professor at East Carolina College in Greenville, N.C., where he was majoring in commercial art.

"I was on campus and I heard this racket so I went around the corner and there was this little man -- he was probably about 5-foot-2, baldheaded with a goatee. A cable had snapped and this stone was teetering on this old truck," Massey says. "I got the stone on my shoulder and forced it back on the truck so it wouldn't fall off."

The professor, who had noticed Massey's brawn, didn't know he was an art student but invited him to take his sculpture class in the fall regardless.

"He said he needed some strong students in the sculpture department," Massey recalls. "I still have the small piece from his class that I carved in marble. I liked the idea of working with my hands, of manipulating the stone, pushing it back and forth, and that's how I got started in stone carving."

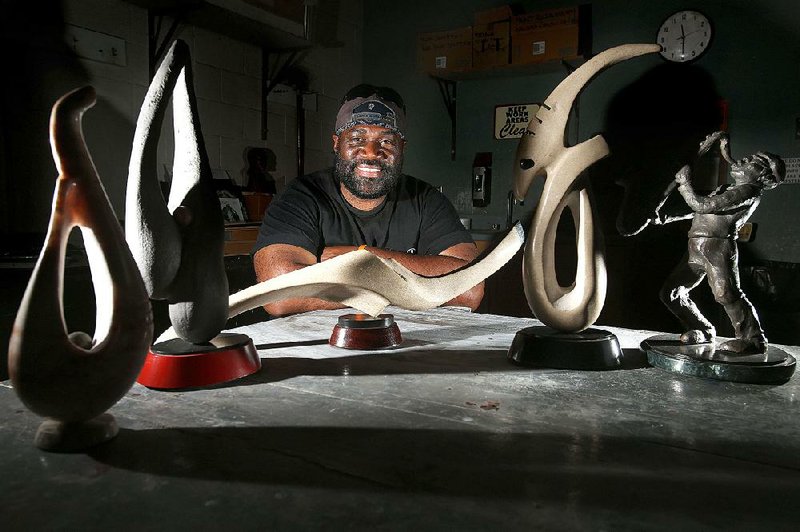

Massey was hired by UCA in 1988 as an assistant professor. Since then he has created artwork that stands in Little Rock's Riverfront Park, CARTI's sculpture garden, Russellville High School and the Grammy Museum in Cleveland, Miss. In 2006, he received the Governor's Award for Individual Artist, and he was commissioned to create monuments to Silas Hunt, the first black student to attend the University of Arkansas School of Law and former Arkansas Gov. Sidney McMath.

Last weekend, during the National Conference of Contemporary Cast Iron and Practices in Birmingham, Ala., he received the Charles Hook Award, granting him a solo exhibition at the Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark.

Massey was commissioned to create a sculpture that hangs on the wall of the $16.7 million Donaghey Hall at UCA. Otis, a 15-foot long, 8-foot wide, 2,000-pound stainless steel bear, was unveiled at the hall's grand opening in 2016.

"Otis is one of my favorite characters from Andy Griffith, growing up in the '60s," Massey says.

When he took the job at UCA, Massey didn't expect to be there long.

"I came planning to stay five years and move on," he says.

One of his uncles had been stationed at the Blytheville Air Force Base and his home had been hit by a tornado. And he had heard about the 1957 desegregation crisis at Little Rock's Central High.

"Those were the things that stuck in my mind about Arkansas," he says. "Then I thought about it -- Arkansas, Conway, virgin territory. They don't have a stone carver in the area. Now, they still don't have an African-American stone carver here in the state. Other people dabble in stone but not like what I'm doing."

He had just graduated with a master of fine arts degree from Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge.

"I had done 1,500 brochures, with my resume attached," he says. "I folded them up by hand, licked all the stamps and put on the addresses of all these various galleries, museums, schools, and just sent them all out. No response."

He heard about the job at UCA and applied, unaware that he was one of 300 who wanted the position.

"They flew me out and I interviewed and before I even got on the plane to go back to Baton Rouge, they called my wife and said, 'Tell your husband thank you for the interview and we appreciate what he did,'" he says.

Massey, who has two older sisters and two younger sisters, hadn't expected to attend graduate school. He lettered in baseball, football and basketball in high school, although his interest in art was constant. He was called upon to do bulletin boards, banners and fliers, and he painted a bulldog -- his school's mascot -- that still hangs in the high school today.

"I never had a lot of encouragement. I didn't get a lot of support, even from my own family, when I was in undergraduate because they were like 'Art major? Hmmmm. Go to school where you can get something and make some money, make a living,'" he says. "My dad was in law enforcement in the latter part of his career and he talked about me maybe being a highway patrolman. He thought that would maybe be a better route. I didn't want to go that route."

SNEAKING STUDENTS INTO THE STUDIO

At East Carolina University, he sneaked underprivileged students into an art studio after hours.

"We got some clay out and stuff and we were just making artwork," says Massey, who didn't see his professor watching. "That Monday I got called into his office and I thought, 'OK, I've been busted.' And he said have you ever considered teaching? He said, 'I saw what you did this weekend for those kids and I think you'd be great teacher.' I thought, 'Wow, I didn't see that coming.'"

Massey later had an accident with a table saw while making furniture for his apartment, cutting off four fingers on his left hand. He made his way to the dean's office after the accident, and he remembers a tiny woman trying to wrap her jacket around his massive shoulders to keep him warm and prevent him from going into shock before an ambulance arrived.

"I couldn't do anything for about a year and a half," he says. "Once the healing process started I had to go through occupational therapy and physical therapy. I really hated them -- they made me do stuff I didn't want to do because it hurt so bad -- but if it hadn't been for those courageous people I wouldn't have my function back. I have limited function."

Norman Keller, one of Massey's former East Carolina professors, admires his rebellious streak.

"He's one hard-working guy. He really, really just went his own way and sometimes didn't listen to me altogether," Keller says. "He was told not to use that shop and he managed to get in there. That's my Bryan, though. He would go his own way but that was one of the things I liked about him. He was so determined to do things his own way -- to do them the way he wanted to do them."

After graduation, Massey took a job in the forensics unit of the state-run Dorothea Dix Hospital. He was living at home, saving money to start his life, but he and his mother had a disagreement and she told him if he couldn't abide by her rules he should leave. He was homeless for two months, living in a 1977 Chevy Impala that belonged to his employer.

"I would sleep in that car, with nothing to eat for days on end," he says. "I would go visit my sisters to take a shower and stuff like that. I was just bouncing around from place to place."

He reconciled with his family and lived at home again briefly before marrying Delphine, who he met in college, in September 1985. In January 1986, Keller invited him on a road trip to pick up some sculptures and to visit some graduate school programs.

"He called me out of the blue. That was a God moment. I was at a point where I was frustrated and I wanted to create but I didn't have the means to create," he says. "I was still drawing and doing watercolors for people for ink washes and things like that -- $50 here, $75 there. I was itching to get back to stone carving. I was in an apartment complex with no facilities for doing that and grad school was a way of doing that."

Delphine worked full time as manager of a fast food restaurant to support the family while Massey went to graduate school.

"She wanted me to focus on my studies," he says, adding that he told her when he was done he would make sure she never had to work again unless she wanted to.

He worked two jobs, teaching at UCA and doing four 10-hour shifts at a distribution center, so Delphine could be a stay-at-home mom to their now-grown children -- Junia, Bryan Jr. and Javan, all of Conway.

His parents, Margaret and Leon Massey, were blue collar workers, holding various manufacturing jobs.

"I was a latchkey kid and I got in so much trouble," he says. "I didn't want our kids to come home to an empty house."

Brenda McClain promotes Massey's work as artist representative. She met him when Conway gallery Art on the Green, where she was director, was hired by the architectural firm Polk Stanley Wilcox to find a sculptor to do the piece for Donaghey Hall.

"I had talked to sculptors all over the world," she says. "I talked to a wonderful sculptor in Denver, and I think it was Denmark as well. We wanted something really significant for the wall. Maybe it was because Bryan knew the school but in my first meeting with him he knew immediately what we needed and just started sketching his ideas."

CHAIRMAN OF THE DEPARTMENT

Terry Wright, dean of UCA's College of Fine Arts and Communication, notes that Massey has a big following.

"He's got a long history here and he knows so many people around in the arts community in the state as well as around the country. It kind of blows my mind how many people know him, as an artist," Wright says. "I was particularly excited when an opening came to chair the art department here and I approached Bryan about doing that because I thought he would be a really good person to do it."

Massey had turned down the promotion to chairman three times before accepting the job in July 2018. He had filled in as chairman when a previous chair had back surgery.

"I got a little taste of what the administrative side is like," he says. "But after much prayer and talking to friends and realizing that I could make a difference in this position I put my name in the hat and entered the interviewing process with the dean in his office."

Wright calls Massey a pioneer.

"He was one of the few African-American faculty members back then, when he first got here," Wright says.

Being a pioneer hasn't always been easy for Massey. Not long after he started his job at UCA, he filed a complaint about university's routine practice of canceling classes -- and contracts -- if not enough students signed up.

"There's nowhere in the contract that said if the courses don't make they cancel the classes," he says. "I was a new father, I didn't have any income coming in the summer. I was relying on this summer job to teach. Now we don't have contracts here, we have letters of appointment."

Sometime later, students approached him with concerns about a clause in the preamble to the UCA constitution, specifying that the school was established for the education of white students.

"These were black students -- at the time probably maybe 6 percent of the student population was minority," Massey says. "When I read it I'm like, 'This is appalling. This is dated back in 1989. This language should have been taken out -- who missed this?' We went to a board of trustees meeting to address this but because we were not on the agenda beforehand they wouldn't hear us, so in protest the students got up walked out and I walked out with them. I guess I was viewed as a troublemaker to some people."

His insistence that the clause be removed garnered death threats.

"The FBI advised me to send my wife and children to North Carolina to my mother-in-law's for about a month until the investigation was done," he says. "I said I wasn't leaving -- they weren't going to run me off."

Massey stayed -- much longer than the five years he anticipated when he first arrived.

He expects to be around to see the projected 2022 opening of the $20 million, 114,000-square-foot Windgate Center for Fine and Performing Arts, which will include space for music and theater programs and performances as well as an exterior space for three-dimensional art.

His administrative responsibilities mean he doesn't get as much time to sculpt anymore. He opts to create only when he has a block of several hours. He prefers to work from 12 to 12 -- he doesn't care if that's 12 a.m. to 12 p.m. or vice versa. The new facility will not only provide a more central location for fine art students currently housed in three buildings, it will afford him a covered outdoor space so he can work, rain or shine.

A 2,500-pound piece of Indiana limestone, which he refers to as his "retirement stone" waits outside the studio. Just as with other stones, he has already looked at it and determined what it will be when it's finished.

"When I'm done with that, I'm retiring," he explains. "I'm just going to walk away and leave it there."

• DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH: Dec. 7, 1960, Goldsboro, N.C.

• MY CREATIVITY IS FUELED BY: My relationship with God.

• FIVE PEOPLE LIVING OR DEAD THAT I WOULD INVITE TO AN ART EXHIBIT: My mom and dad, so they would understand what I was doing; Richard Hunt, a Chicago artist who inspired me when I was younger, Jacob Lawrence, another artist who is deceased; and former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice.

• MY HAPPY PLACE IS: The mountains, watching the sunset. When I was in California working for the summer I would go up into the hills of Berkeley and watch the sun set over Alcatraz.

• A MOVIE I SAW RECENTLY AND LIKED WAS: Black Panther.

• THE BEST ADVICE I EVER GOT WAS: From my dad, who said, "Son, you can't tell grown people what to do."

• MY FAVORITE MEAL IS: Medium well-done T-bone steak.

• MY MOST VIVID CHILDHOOD MEMORY: The day my dad stood up to the Klan in the grocery store in my hometown.

• MY BIGGEST PET PEEVE: Thieves and liars. When I was homeless and I didn't have money to buy food, my parents raised me not to steal and lie and I would rather not eat than steal somebody else's food. I saw how hard my parents worked to bring up us five kids.

• ONE WORD TO SUM ME UP: Defiant

High Profile on 04/14/2019