Given who she really was, the military had little choice in how it described Shannon Kent. They said only that she was a "cryptologic technician," which anyone might assume meant that her most breakneck work was behind a desk.

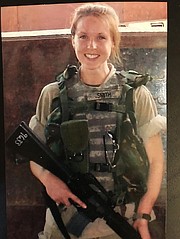

In reality, she spent much of her professional life wearing body armor and toting an M4 rifle, a Sig Sauer pistol strapped to her thigh, on operations with Navy SEALs and other elite forces -- until a suicide bombing took her life in January in northeastern Syria.

She was, in all but name, part of the military's top-tier special operations forces. Officially a chief petty officer in the Navy, she actually worked closely with the nation's most secretive intelligence outfit, the National Security Agency, to target leaders of the Islamic State.

The past few years have seen a profound shift in attitudes toward women in combat roles.

Since 2016, combat jobs have been open to female service members, and they have been permitted to try out for special operations units. More than a dozen have completed the Army's Ranger school, one of the most challenging in the military. Some have graduated from infantry officer courses, and even command combat units. And in November, a woman completed the Army's grueling Special Forces Assessment and Selection course, the initial step to becoming a Green Beret.

Yet Kent illustrates an unspoken truth, that for many years women have been doing military jobs as dangerous, secretive and specialized as anything men do.

She would sometimes muse that conversation, even with people who had top security clearances, would be simpler if she could just join a special operations unit.

"She'd tell me, 'You can say what you do in two words, but I have to explain over and over to people what I do, and half of them don't believe me'," said her husband, Joe Kent, who recently retired after a 20-year career in the special forces.

"As the years went on, she wished she could just say, 'Hey, I'm Joe, and I'm a Green Beret.'"

"In many ways, she did way more than any of us who have a funny green hat."

Only in death can friends and family talk about a life that showed just how far women had quietly advanced into the nucleus of the nation's most elite forces.

"Her job was to go out and blend her knowledge of cryptology and sigint and humint to help the task force find the right guys to paint the 'X' on for a strike or a raid," Joe Kent said.

Cryptology is code breaking; sigint is signals intelligence, like intercepting and interpreting phone calls and other communications; humint is human intelligence, the art of persuading people, against their instincts, to provide information.

At 35, Shannon Kent was expert in all three. Her husband credits a knack for gleaning information picked up from her father, a lifelong police officer.

"She understood how all the pieces came together," he said. "She wasn't just relying on local informants. She knew how to fill in the gaps through her knowledge of different intelligence capabilities. She was kind of a one-stop-shop for finding bad guys."

Kent spoke a half-dozen Arabic dialects and four other languages. She was one of the first women to complete the rigorous course required for other troops to accompany Navy SEALs on raids. She could run a 3:30 marathon, do a dozen full-arm-hang pull-ups and march for miles with a 50-pound rucksack.

She did this while raising two boys, now ages 3 and 18 months, and, for a time, battling cancer.

She used her five overseas combat deployments to master the collection of human intelligence, gaining the trust of tribal leaders, merchants, and local government officials who confided in her, often at great risk to themselves.

That is the kind of mission she had been on Jan. 16, when a bomber killed her and three other Americans at a restaurant in Manbij, Syria. The Islamic State claimed credit for the attack. She became the first female service member to die in Syria since U.S. forces arrived in 2015.

More than 1,000 people attended Kent's memorial service at the U.S. Naval Academy Chapel in Annapolis, Md., where she was posthumously promoted to senior chief petty officer and awarded five medals and citations. The awards described her special operations work and also said she had been the noncommissioned officer in charge at the NSA's operations directorate for four years.

By the time the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were reaching their highest pitch, women had been trained as intelligence collectors, linguists, interrogators and other specialties that put them on the front lines.

That Kent's last assignment was in northeastern Syria, where American forces work with the Kurdish militia, was fitting: There are many female fighters and commanders in the Kurdish forces.

"Women have been on the front lines with special operators for 16 years," said Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, author of a book about female troops working with elite forces in the combat zones of Afghanistan. "But because that community is unseen and so rarely talks about their work, it's been hard to know how much women have done."

Kent developed skills that have become critical over the past two decades, including the immediate exploitation of documents, hard drives and other intelligence found during raids, and sophisticated methods of targeting that combined eavesdropping, human intelligence and relationship mapping.

In her first combat rotation, in 2007, she worked with the Joint Special Operations Command in Balad, Iraq. She did two more rotations in Iraq before a long stint at a remote outpost in Zabul province, Afghanistan, in 2012, where she won awards for being a top human intelligence collector and linguist.

Early in her career her language skills and easy manner had made her good at "tactical questioning" of people during missions. "That was her foot in the door," Joe Kent said.

"Back then I don't think SEALs were enthusiastic about talking to locals, and Shannon found a place where she could be of value, and she poured her heart and soul into it," he said.

The Kents first met during intelligence targeting training at Fort Belvoir, Va., where Joe Kent had been assigned to an Army Special Operations command after seven deployments to Iraq. They were married Christmas Eve 2014.

"We got set up by another girl who does the same stuff," Joe Kent said. "It's a pretty insular type of community, and we had similar life experiences."

But for a cancer diagnosis -- and the Pentagon bureaucracy -- Shannon Kent would not even have been in Syria.

After so many hard missions and becoming a mother, she had decided to become a clinical psychologist and treat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

That meant becoming a Navy officer and spending six years studying and training. She was scheduled to go to the Navy's Officer Development School in Rhode Island in June, and to begin her classes for her doctorate in the fall.

But she had been diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2016. She told her husband, then on a deployment, only after the surgery was successful.

"She just sent me a picture of her throat scar and said, 'I had a little cancer, but I got it cut out. I didn't want to bug you,'" Joe Kent said.

Even though she was considered cancer-free, the military's rules blocked her from becoming a commissioned officer. But the rules still allowed her to deploy to the most hard-fought combat zones.

She pressed her case with congressional representatives, and her husband followed up with the Navy after her death. This past week, the Navy modified its rules to make it easier for enlisted service members who wish to become officers to petition for medical waivers.

"The Navy fixed everything that kind of screwed Shannon," Joe Kent said.

SundayMonday on 02/10/2019