When the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled in early 2018 that a sentence in the state constitution protecting the government from lawsuits was to be taken literally, attorneys and lawmakers who had been operating under a much different precedent for 20 years said the decision created more questions than answers.

In the year and a half since that first decision, state attorneys sometimes have had success in raising claims of sovereign immunity to dismiss lawsuits over wage disputes and whistleblower claims.

Yet in other decisions, the justices have held that some instances allow for the state to be made a defendant in its courts.

A web of more than a half-dozen decisions in the recently ended term of the high court has clarified some aspects of the latest sovereign immunity precedent, attorneys said in recent interviews. At the same time, some said there were questions yet to be resolved by the court.

"It looks like the court has backtracked a little bit since Andrews," said Little Rock attorney Alex Gray, referring to the court's Jan. 18, 2018, decision in the case Board of Trustees v. Andrews, in which a 5-2 majority of the court re-established a strict standard for immunity.

"But the constitution remains the same," added Gray.

The basis of the justices' ruling lies in Article 5, Section 20, of the Arkansas Constitution of 1874. That section simply states: "The State of Arkansas shall never be made defendant in any of her courts."

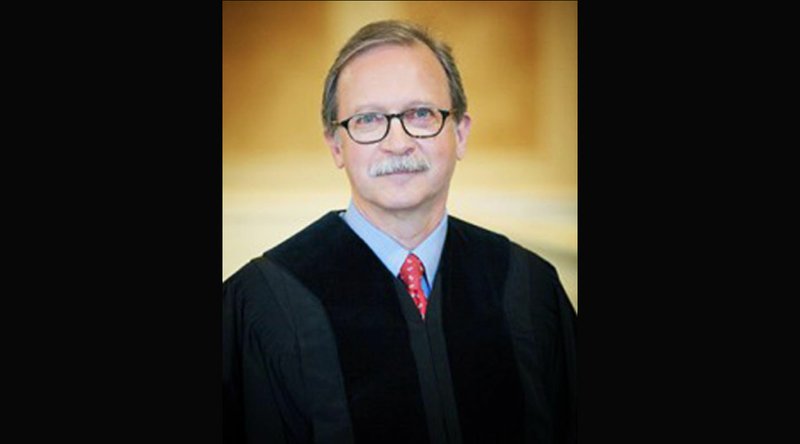

In Andrews, Chief Justice Dan Kemp wrote for the majority that the court would interpret that sentence "precisely as it reads."

The impact of the decision was to overturn about 20 years of precedent that had allowed the Legislature to pass laws waiving the state's immunity, such as in the Arkansas Minimum Wage Act. The plaintiff in the case, Matthew Andrews, had sued under that minimum-wage law, seeking back wages from a public community college.

In October 2018, another 5-2 majority decided that sovereign immunity did not bar a challenge to Arkansas' newly enacted voter-identification law, because the lawsuit in question sought relief other than a money judgment. Several attorneys who spoke to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette said that case, Martin v. Haas, added the most clarity to the court's views on sovereign immunity.

In Haas, Justice Robin Wynne wrote that because the plaintiffs were seeking to block the state from implementing its voter-ID law through "declaratory and injunctive relief, not money damage," the state could not raise sovereign immunity in its defense. (Wynne and the court's majority otherwise found the voter-ID law constitutional.)

In decisions after Haas, the court's majority has clarified that declaratory or injunctive relief can be sought when a state agency or official is acting illegally, unconstitutionally or ultra vires, which is a Latin phrase used legally to say "beyond its authority."

A ruling in December, Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission v. Hurd, upheld the Arkansas Administrative Procedure Act and determined that sovereign immunity did not bar the judicial review of an agency decision reached by the commission. Again writing for the majority, Wynne found that the circumstances of the case differed from Andrews because the commission's "role in the proceeding is that of a tribunal or a quasi-judicial decision-maker rather than a real party in interest."

Yet still, several months later, with Wynne again writing for the court's majority, the justices struck down portions of the Arkansas Whistle-Blower Act in a suit filed against state Treasurer Dennis Milligan by a former employee. In Milligan v. Singer, the court ruled that the employee, David Singer, was not seeking injunctive relief, but a claim for monetary damages barred by sovereign immunity.

Grant Ballard, a Little Rock attorney, said the Hurd case muddled the court's rationale behind the Andrews decision because both the Arkansas Minimum Wage Act and the Administrative Procedure Act -- and likewise the Whistle-Blower law -- were drafted by lawmakers.

"It's unclear in what circumstances, if any, the Legislature can allow a suit against the state to proceed," Ballard said. "Attorneys who represent businesses that are regulated by the state still have a lot of questions."

Ballard represented six Arkansas farmers in a lawsuit challenging the state Plant Board's regulations on the herbicide dicamba. In June, the justices ruled 6-1 that the lawsuit was not barred by sovereign immunity.

Not all attorneys who have litigated the issue in court, however, agreed that the majority lacked a consistent approach.

"There could always be some factual scenario that you or I aren't thinking about," said Scott Trotter, an attorney who represented Monsanto -- the manufacturer of dicamba -- in a related lawsuit against the Plant Board.

"Generally speaking, in my view, it's pretty clear," Trotter said.

CLAIMS COMMISSION

For Andrews and others seeking money damages from state entities, Kemp wrote that they should seek relief from the Arkansas Claims Commission, an administrative agency established in 1955 to hear monetary claims against the state. Critics of the court's decision, however, argued that the Claims Commission process is too political as its rulings must be reviewed and approved by lawmakers. There are times when lawmakers have altered the commission's monetary judgments.

In interviews with the Democrat-Gazette in the days after the Andrews decision, lawmakers who sit on the Claims Review Subcommittee -- which reports to the Legislative Council -- said they expected their workload to increase.

Since the Andrews decision, the number of claims filed with the Claims Commission have jumped by two-thirds.

In fiscal 2017, there were 789 claims filed with the commission, according to its director, Kathryn Irby. That number rose the next fiscal year, when Andrews was decided, to 1,074 claims, and jumped to 1,303 claims in fiscal 2019, which ended Sunday.

The commission has not added to its staff of five to handle the increased caseloads, said Irby.

The commission's decisions are reached by five part-time commissioners, who are appointed by the governor.

"We cannot directly attribute the increase in claim filings to the Andrews decision," Irby said in an email. "Since Andrews, there have been less than five claims filed alleging violations of the Arkansas Minimum Wage Act."

One justice who has been a frequent dissenting voice on the court's sovereign-immunity rulings, Karen Baker, at first warned that the justices' decision to overturn precedent could have broad implications. But as the majority has narrowed its application of the doctrine in subsequent rulings, Baker has criticized the other justices for being inconsistent.

In one recent dissent, Baker wrote that "the majority cannot pick and choose when an exception or exemption may apply."

Marian McMullan, a Little Rock attorney who recently argued against the use of sovereign immunity in a right-of-way lawsuit, said that the court's majority had been "quite consistent" since Andrews in ruling that sovereign immunity did not apply in cases where the state is alleged to have acted illegally.

However, she said the contrast between that line of reasoning and the Andrews decision still raised questions.

"Why isn't that considered an illegal activity if they aren't complying with the law of compensation?" McMullan said. "No one has been able to answer that."

A Section on 07/05/2019