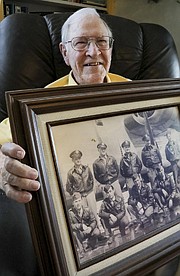

On a gray, drizzly day 75 years ago, William “Dub” Toombs of North Little Rock reported for duty the morning of June 6, 1944, on an air base near the English town of Ipswich.

As a flight engineer with the 493rd Bombardment Group of the Eighth Air Force, Toombs, 95, said the day was business as usual: up at 4 a.m., then breakfast in the mess hall before heading to the briefing room for that day’s mission.

“They came down and pulled the curtain back and the executive officer said, ‘Gentlemen, we’re invading the continent this morning,’” Toombs said. “That’s how we knew there was going to be an invasion.”

What has become known as D-Day — the invasion of Normandy by about 160,000

Allied troops during World War II that eventually led to the liberation of Europe from Hitler’s Germany — was Toombs’ first mission.

“I never saw so many airplanes in my life,” Toombs said. “Everything that could fly, flew that day.”

[D-DAY 75TH ANNIVERSARY: See full 48-page section in today's digital edition]

At 7 p.m. today on HBO, Toombs and eight other airmen will be the voices accompanying film footage long thought lost of air combat over Europe many months before D-Day.

The Cold Blue, a documentary by Vulcan Productions is comprised of color film shot by Oscar-winning director William Wyler, who joined the war effort in the summer of 1943 specifically to chronicle what B-17s faced as they bombed factories and military installations.

Director Erik Nelson, who is president of Creative Differences, recently discovered nearly three dozen reels — 15 hours total — of Wyler’s footage in the vaults of the National Archives. Wyler used part of the footage for the 1944 documentary, The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress, which tells the story of a U.S. Army Air Forces’ B-17 bomber.

The B-17s flew daylight raids over Europe and suffered heavy losses. One of the cinematographers of the 16mm color film, Harold J. Tannenbaum, was killed in France when the plane he was in was shot down by enemy fire.

“There were a lot of outtakes and film he [Wyler] didn’t use for the Memphis Belle. The film was in extremely bad shape. They didn’t know if it could be cleaned up, but they were able to completely redigitize the film,” said Dr. Nancy Toombs, Toombs’ daughter. “It’s like it was made today. They came up with the idea, ‘Why don’t we do a documentary in the present day and let’s talk about what Wyler did?’”

Nelson’s team traveled the nation interviewing nine aging veterans who flew on B-17s.

From the beginning, the producers reached out to Nancy Toombs, who is a past president of the Eighth Air Force Historical Society. She had followed her dad as he traveled the nation and to air bases of Europe getting to know other airmen at reunions and battle sites.

It was Nancy Toombs who suggested to the filmmakers that they try to find a veteran who flew each of the 10 positions on the B-17: pilot, co-pilot, bombardier, navigator, top turret gunner/engineer, radio operator/gunner, ball turret gunner, right waist gunner, left waist gunner and tail gunner.

Dub Toombs can be heard in the documentary reliving the harrowing 28 bombing missions — eight on a B-17 bomber and 20 more on a B-24 — he survived. The horror, he said, is still with him today.

“Fear. Absolutely. Without a doubt. Completely. I ’ v e h e a r d people say, ‘Oh, I wasn’t scared.’ If you wasn’t scared, there’s something wrong,” Toombs said. “ Yo u d o n ’ t p a n i c . I t ’ s like someone pointing a gun at you and threatening to pull the trigger. You don’t panic, but at the same time, you might be sweating like the dickens. We did our job. We had people come back and tell the flight surgeon that, ‘I just can’t do this. I can’t fly. No way. I will jump out of the airplane first.’”

Dub Toombs saw many planes fall from the sky and the resulting carnage that comes from warfare. He was aboard his own plane when it crash-landed in a turnip field near Brussels after two engines were shot out.

“We talked about it. Paris had been liberated. Brussels had been liberated. We were about the same distance from each city and we decided we’d try to go to Brussels. We flew for probably close to two hours,” he said. “We knew we weren’t going to get back to England. No way to get across the channel. We discussed whether to ride the plane down or bail out. We couldn’t bail out then because we were over enemy territory. If you bailed out then, you were going to be a prisoner of war if the civilians didn’t kill you first.”

“They had just been liberated. Everybody got out all right and we spent the night there, the guest of the Brussels people,” he said. “They were celebrating wildly.”

Nancy Toombs said she grew up at her father’s knee hearing war stories. She remembers a footlocker on her grandmother’s porch and a picture of her uncle, Wilton P. Toombs Jr., who was killed in an air battle.

“There were all these uniforms in the there, and I would walk around in those uniforms re-enacting the war,” Nancy Toombs said. “I was drawn to that. In my day, women couldn’t fly, couldn’t train. I had a secret love affair with airplanes. I was exposed to it, was around it and knew about it.”

She knows, though, that recollections of a bygone era will soon disappear as World War II veterans, most well into their 90s, pass away.

“This has been a labor of love for me. I do it because I want to, and I’m crazy about these guys,” Nancy Toombs said. “Most of them do not have children who are interested. If your dad didn’t talk about it growing up, you didn’t know about it. The grandchildren are even less interested. We’re going to fade away. There’s no doubt about it. There’s not going to be enough of us to continue into perpetuity.”

The Cold Blue documentary did a good job of capturing the reality of the World War II experience, Dub Toombs said.

“It couldn’t have been any better because it was all actual film, actual combat,” Dub Toombs said. “There was nothing staged about it. You can’t be any more real than that.”