It seems it's not a protest in the age of social media without a photograph. From the women's marches to Black Lives Matter protests to sit-ins for a Green New Deal on Capitol Hill, participants have flooded the digital landscape with photos of their activism: demonstrators brandishing signs and packing America's streets, plazas and corridors of power.

But while social media makes this act of sharing protest imagery seem like a new innovation, it's actually an organizing tool with roots almost two centuries old. Antebellum abolitionists pioneered the use of photography as a tool for social movements, and in the process they heightened their sense of solidarity and urgency, exacerbating the political crisis over slavery.

Abolitionists understood that building a movement meant making themselves visible. Early photography offered a bracing new tool for them to do so. Arriving in the U.S. from Europe in 1839, the medium was widely hailed as a means of picturing the world with startling precision.

Though long exposure times and clunky cameras made photography a poor tool to take action shots of slave auctions or floggings in the South, it did offer activists something else: a means of picturing themselves in their ongoing battle against slavery and racism.

In the 1840s and 1850s, leaders and rank-and-file members alike made a concerted effort to craft and share portraits with other activists, to document fugitives who escaped along the Underground Railroad and to circulate images of black and white rebels who helped rescue enslaved people and aimed to trigger slave rebellions.

The reasons for abolitionist pictures were many. For some, seeing an image of a fellow radical could inspire. At least black abolitionist photographer Robert Douglass Jr. felt as much when he copied white activist Abby Kelley Foster's daguerreotype (an early form of non-reproducible photography) into a lithograph to sell. As he wrote to her, "[I]f in regarding your Portrait a single spirit is ... excited to action for the advancement of the great and Holy cause in which you are so indefatigably engaged I shall be amply rewarded."

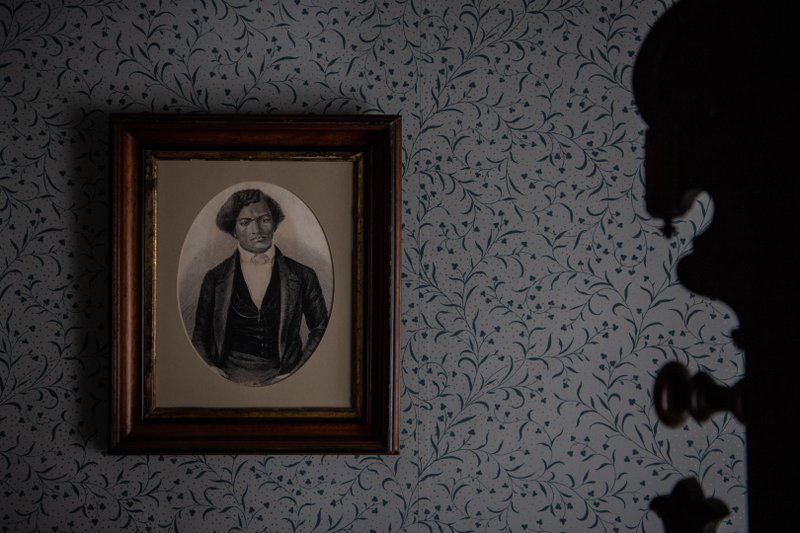

For abolitionist and author Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery, creating photographs served an additional purpose beyond solidarity: demonstrating his fundamental humanity and subverting anti-black racism. These efforts rested upon a crucial insight. As Douglass explained, "man is a picture-making and a picture-appreciating animal," which for him was "an important line of distinction between man and all other animals."

This understanding helps explain why Douglass became the most photographed American in the 19th century with at least 160 separate poses. Douglass took care to portray himself in dignified fashion, regularly appearing in a suit, tie and vest. He did not photograph the scars on his back (nor, from my research, did other fugitives before the Civil War). Photography for Douglass was not a means of documenting the brutality of his previously enslaved condition. It was about taking part in this most human of activities and staking a claim to equal humanity.

Photographs circulated within the movement, knitting it together. Perhaps no one's image spread more than John Brown's. After Brown's failed 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, Va.--a raid he hoped would prompt a revolt among enslaved people--activists feverishly sold and consumed his likeness. One of the most popular photographs depicted Brown with a long beard and hands in his pockets, rendering him as much an old sage of the movement as the firebrand who aimed for violent upheaval.

Such photographs were displayed at public memorials and in abolitionist homes after Brown's execution. Lydia Maria Child wanted "to have every form of his likeness that can be devised, and have no corner of my dwelling without a memorial of him. The brave, self-sacrificing noble old man." Images of Brown and others forged a new type of social movement glue, generating admiration and solidarity.

Abolitionists also made news pictures of dramatic action. This even took place along the networks that made up the Underground Railroad. In Philadelphia and Cincinnati, fugitives stopped to pose for pictures before they traveled onward, and though few of these images survive, written accounts reveal their emotional power.

In her diary, black abolitionist Charlotte Forten described seeing one of these fugitive photographs in Philadelphia--in this case "a daguerreotype of a young slave girl who escaped in a box." (The image likely envisioned Lear Green, who had escaped from slavery in Baltimore by stowing herself away in a chest with minimal supplies.)

Forten was gripped by this image that re-enacted a moment in the fugitive's flight. As she detailed, "My heart was full as I gazed at it; full of admiration for the heroic girl, who risked all for freedom; full of indignation that in this boasted land of liberty such a thing could occur." The photograph, which in this case sparked both anger and admiration, was a captivating new way to witness resistance in action.

Photographs underscored the fierce urgency of the present; they also helped abolitionists stage the future. One of the more remarkable abolitionist images was taken in August 1850 in Cazenovia, N.Y., where activists convened to protest the Fugitive Slave Law. Since the law made Northerners complicit in returning fugitives (fining and jailing them if they failed to help), it was especially repulsive to abolitionists, more than 2,000 of whom met at Cazenovia in shared dissent.

Those who posed for the camera included Frederick Douglass (seated), Gerrit Smith (standing in the center), and Mary and Emily Edmonson (flanking Smith). An early protest image, the daguerreotype visually enacted in miniature form the interracial society abolitionists sought to achieve.

Abolitionists were not the only ones using this new visual technology for political purposes as the national crisis over slavery deepened. In the South, enslavers commissioned studio portraits of enslaved people, especially individual portraits and interracial pairings of enslaved women holding white children. As pro slavery rhetoric, these images suggested bondage was benevolent (hence the well-dressed enslaved people), erasing the coerced labor, violence and commodification of human beings central to the system.

By the Civil War, enslavers had also begun pasting photographic portraits of enslaved people onto want ads to identify them. Technological change, then and now, was not inherently linked to social justice.

But this does little to diminish the visual legacy of abolitionism. Their uses of photography, the "new media" of the antebellum era, initiated a meaningful visual tradition, by which a social movement made itself and its actions tangible.

Talk of "slacktivism" over the past decade has rightly highlighted the limitations of "liking" an article on social media as a means of political engagement. But this critique risks missing the potential of circulating and viewing photos. Looking back at American abolitionism reminds us of the potency of the photograph to forge political communities and spread the news that resistance is happening.

Editorial on 05/05/2019