Arkansas cattle ranchers and their expert advisers in the federal government waged a war on cattle ticks 100 years ago. Then as now, ticks were repulsive blood suckers infested with protozoan parasites. They weakened the cows, sickened the cows, killed the cows and their ubiquity made even healthy cows unmarketable.

Meanwhile, another war raged beside the war on ticks — against it.

There was a war on the war on ticks. As historian David Marquis once put it, the anti-tick-war war didn't have a name, but it did have a ton of TNT. It sprang up anew every spring and summer from 1908 through the 1930s.

I know what you're thinking, if what you're thinking is "Huh?" That's what I said, too, because who wouldn't want to eradicate ticks? Pardon my speciesism, but death to ticks.

Writing for the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, Holly Hope explains that the federal tick-eradication campaign began with a quarantine line in 1891 that was intended to protect Northern cows from Texas tick fever — babesiosis. Even healthy Southern cows sold to northern packers were to be slaughtered immediately once they crossed the line and shipped to their destinations as meat.

That was a hassle, hurt everyone's bottom lines, invited corruption and did nothing to save the tick-burdened farmers or protect uninfected farms below the line.

In the early 20th century, Department of Agriculture researchers worked out plans for dipping cattle in pesticides. Eradication districts were voluntarily formed, and farms inside them dipped stock on a set routine. Big concrete dipping vats were built in three-quarters of Arkansas counties by 1914, with 25 to 40 vats per county. Stockmen wouldn't have to drive their herds farther than 3 miles for a dip.

They helped finance the program by paying a 5-cent-per-head annual tax.

There was general compliance but, Hope writes, obstructionists known as "kickers" arose among small farmers "who did not have the education or economic resources to effect changes at the government level. Their frustrations were expressed by refusal to dip, dynamiting dipping vats, arson of property belonging to pro-dippers and government employees, and verbal threats against those groups — threats that eventually escalated to assault or murder."

And so beginning about 1908 there were frequent news stories in spring and summer issues of Little Rock newspapers about vats dynamited and people wounded, killed or arrested. There also were reasonable-sounding letters to the editor from anti-dippers explaining their belief that the chemicals and the process harmed their herds.

One hundred years ago today, the Arkansas Gazette carried a stringer's report from Hope (the city) that late on May 10, a Saturday night, five men tried to dynamite a dipping vat near Patmos, and three of them were shot by farmers guarding the vat.

The wounded were named Huckleberry, Betts and Hatch.

It is said the dynamiters were in the act of lighting the fuse to explode the dynamite when the guards fired. It is difficult to get the people in the neighborhood to discuss the shooting.

No arrests have yet been made, either for the shooting or for refusing to dip cattle, but warrants, it is said, have been issued.

MEANWHILE . . .

A Wisconsin brewing company named Schlitz began to market itself as "The Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous" in the 19th century. During Prohibition, Schlitz dropped the word "beer" and developed near-beers. A Schlitz ad in the May 14, 1919, Gazette promoted Famo, the "worth-while cereal beverage."

The Anheuser-Busch beverage Bevo having been introduced in Arkansas in July 1916, Famo looks like copycat marketing. And indeed, a history of the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Co. posted online by the Sussex-Lisbon Area Historium of Milwaukee has Schlitz developing Famo in 1917. Not that it matters at this late date.

It's fun to read the description of the new beverage offered to Arkansans, because, you see, Famo was more than a drink.

It is a food. Every time you take a glass of Schlitz Famo you are taking something to eat.

Every compound essential to the human body is present in Schlitz Famo — protein, carbohydrates, mineral matter and water — the only factor absent being fats, and they are formed in the body from the carbohydrates.

They certainly are. But remember — in 1919, fattening was not a negative thing to say about a food or drink. Manufacturers were trying to fatten people up.

PARTY

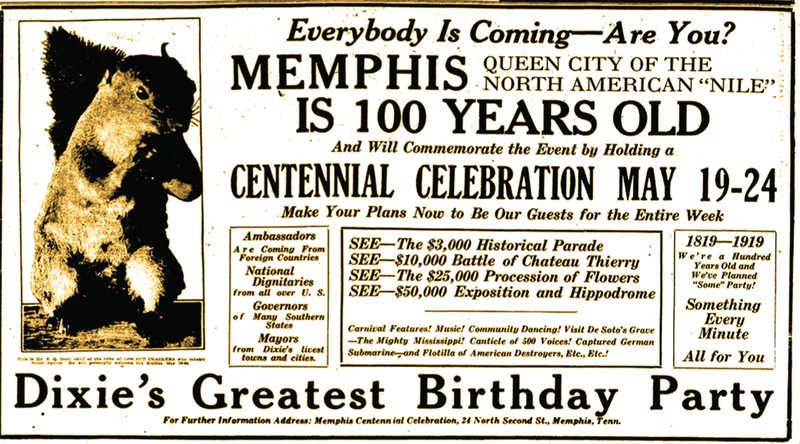

To celebrate its centennial, the city of Memphis planned a festival May 19-24. Organizers clearly thought the promise of vast expenditure would bring visitors a-running: ads touted a $10,000 re-enactment of the Battle of Chateau Thierry, a $3,000 historical parade, a $25,000 procession of flowers, a $50,000 exposition and a Hippodrome.

And for the kiddies, squirrels. If you squint, small type below a photograph of a squirrel in a May 11 ad for the fest introduces Mr. S.Q. Irrel, chief of the tribe of 1,000 Nut Crackers who inhabit Court Square.

I was enjoying imagining the organizing committee fretting about rodents in public spaces and deciding to make a virtue of a deficit, but a bit of online research soon revealed that a section of Court Square was nicknamed "the squirrel pasture." It was Memphis lore.

If nothing else, today's Old News should illustrate that certain stories and ads we find hilarious were not necessarily trying to be funny in 1919. But at least one that at first blush seems serious was meant as a joke. "Wanted for murder" ads appeared occasionally without other explanation in the Gazette.

They describe someone 5 feet, 10 inches tall, weighing 191 pounds, with an iron-gray upward curling mustache and a withered left arm.

This person is wanted for "atrocities against humanity."

Neither a bounty hunter's ploy nor creative marketing for a vaudeville show, they were house ads — ready-made blocks of type the composing room could slip into unsold ad spaces. The "murderer" that readers were to report on sight was the former German kaiser, Wilhelm II, who opposed the Allies during a war that has a name, and not just one name: In 1919 they called it the "Great War"; today we say "World War I."

Email:

cstorey@arkansasonline.com

ActiveStyle on 05/13/2019