Preterm birthrates in Arkansas are getting steadily worse, according to a report released today by the March of Dimes.

For the first time since 2010, the state will receive an F on a report card focused on maternal and children's health and compiled by the nonprofit. Only three other states have higher rates of premature births.

Black families are most affected in Arkansas, with a preterm delivery rate -- defined as babies born before 37 weeks of gestation -- that's 47% higher than the rate for all other women in the state.

"We need to reverse this trend," said University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences neonatologist Dr. Whit Hall. "We have a long way to go to be able to figure these things out."

Hall said the findings point to a "huge burden" that can cost families hundreds of thousands of dollars and subject babies to painful procedures and poor health outcomes.

For Arkansas, the report estimates that the average preterm birth costs $59,000, which includes medical care for the mother and child, special-education services and lost productivity.

Preterm birthrates have been rising in the state since 2016, which was also the first year the March of Dimes used new methodology for calculating the rates, said Faith Sharp, the group's Arkansas maternal child health and governmental affairs director.

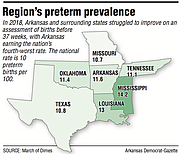

Data from 2018 marked the fourth year of increases in the national preterm birthrate, which is now 10%, a news release accompanying the report said.

While the increase in Arkansas was only a slight uptick -- climbing to 11.6% last year from 11.4% for 2017's babies -- it pushed the state into the "failing" category, accompanied by Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, West Virginia and Puerto Rico.

Sharp said advocates and policymakers in Arkansas need to "sit down and start planning."

"These are our babies. These are our moms. ... We really need to heavily rely on what's happening in other states," she said. "You know, maybe there's a key."

Within Arkansas, preterm birthrates rose between 2017 and 2018 in Benton, Sebastian, Craighead and Faulkner counties, with improvements seen in Pulaski and Washington counties.

Full county-specific data from 2018 isn't yet available, but Monroe, St. Francis and Sharp counties had the highest preterm birthrates from an average of 2015-17 numbers.

Even "high-resource" counties, however, posted numbers above the national average, which "really kind of speaks to the fact that it's definitely not one factor," said Arkansas Department of Health senior physician specialist Dr. Sam Greenfield.

Hall called the increase in premature births a "national catastrophe," adding that although Arkansas has a low mortality rate for preterm babies, its overall infant mortality rate is stubbornly high because of preterm deliveries.

"The U.S. is facing an urgent maternal and infant health crisis," the March of Dimes said in its release. "This crisis is not just about the health of babies born too soon, it's about those we've lost."

NO EASY ANSWERS

Researchers are still learning about the underlying factors for preterm birthrates in Arkansas, where gains seen earlier in the decade are gradually being erased.

While there are lots of theories, providers say it's a complex problem with precise causes that have proved hard to nail down -- "the exact why is never quite easy to say," said Greenfield, who also practices at UAMS.

Extremes of reproductive age (people who are very young or old when they get pregnant), genetic factors, a previous preterm birth and lack of access to prenatal care all have been linked to preterm deliveries.

Falling numbers of people with insurance coverage as well as drug use during pregnancy -- especially of methamphetamines -- also are on local doctors' radars as possible connections.

General population-health issues also seem to contribute to more complications, such as pre-eclampsia or gestational diabetes, said Arkansas Family Doulas owner and founder Sondra Rodocker. Doulas are nonmedical individuals trained to support people through childbirth and other health-related experiences.

"People are typically becoming predisposed to some of these issues before they even get pregnant, and then pregnancy just further complicates it," she said. "Growing a tiny human, it takes a lot of work."

Clinicians do know that being born too soon is connected to health problems and expensive treatments that can be traumatic for infants and families, starting with lengthy hospital stays immediately after birth.

Babies born ahead of schedule are "subjected to numerous procedures that are developmentally unexpected," such as undergoing surgery or being put on a ventilator, Hall said.

"We think primarily in terms of the short term, the hospitalization. But we also have to think of the long-term issues."

Premature babies can struggle to eat or put on weight. Later, they can have problems with cognition and attention, and they are at higher risk of developing cerebral palsy or of dying suddenly as infants.

What causes preterm birth to disproportionately affect black families in Arkansas also isn't well understood, though it's likely "multifactorial," Greenfield said.

Socioeconomic status, a few genetic markers related to issues such as membrane ruptures, and bias among health care providers -- which may make women less comfortable seeking care -- all could play a part, experts say.

Systemic racism -- a bias embedded in institutions or processes that are thought to disadvantage members of minority groups -- also might contribute, Sharp said.

For example, some women may live in communities with limited access to transportation or have unstable housing situations with no fixed address.

"It makes it harder ... for those women to link to resources that would [support] a healthy pregnancy," she said.

MATERNAL EFFECTS

Clinicians and advocates said tackling high preterm birthrates in Arkansas will take mobilization by lawmakers and health care providers, including addressing "maternal health deserts" in many counties.

"I think that it goes all the way from grassroots efforts to policy changes," Sharp said.

State Rep. Mary Bentley, R-Perryville, who co-sponsored Act 829 of 2019 to found an Arkansas maternal mortality review committee, said policymakers will need to look carefully at data to lower preterm birthrates on a statewide basis.

"We have these little pockets, here and there, that are doing things, but nobody's coming together," she said.

Providers cited the need to ensure easy and widespread access to prenatal care during pregnancy, which correlates with reduced preterm birthrates.

Those visits establish "a degree of comfort, rapport, but also it's education," Greenfield said. "That provides an opportunity for prevention or early detection."

Some research shows good outcomes for group prenatal care, an approach the March of Dimes has implemented lately through clinical partners in Northwest Arkansas.

Sharp said efforts in that area have had a major effect on the Marshallese community, which now has the second-lowest premature birthrate (behind Hispanic women) in the state.

Telemedicine programs connecting smaller hospitals to the state's major birthing centers, as well as women with obstetric services, also have had a positive effect, clinicians said.

In Little Rock, a chapter of a program founded through the historically black Zeta Phi Beta sorority offers free classes during pregnancy in an attempt to prevent preterm births, low birth weights and infant deaths.

Stork's Nest program director Beverly Cook said the course is geared toward people with low incomes, but anyone can attend. It teaches pregnancy and parenting skills and offers incentives for getting prenatal care.

That's important for black women, who have a higher risk of preterm delivery, she said.

Kimberly Titus, 34, recently went through the course while she was pregnant with her son, Kingston.

Titus' previous child, Queen, was born a week premature. The Little Rock mother took her kids to Stork's Nest this year while she learned more about health during pregnancy and about postpartum care.

"They got to color, [and] I got to learn some things that I may not have learned about," she said.

A Section on 11/04/2019