Because the New York Film Festival is the New York Film Festival (even their numbering system is confusing as they go not by year but by editions of the festival), the press aren't invited to spend a week, taking in multiple screenings a day, a la Toronto International Film Festival, or Sundance. Instead, their press screenings are mostly before the festival even starts (as our accreditation makes abundantly clear, our badges do NOT grant us access to the public screenings) and are spread out over several weeks, one or two films a day.

So this year, I chose a two-day, two-night spread that allowed me to see four films, including this year's Main Event: The world premiere of Martin Scorsese's hotly anticipated mob movie The Irishman, which stars Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Al Pacino and couldn't possibly be more New York than if it gloated about the Yankees while eating a folded slice from Di Fara's. I left on a Wednesday in late September and returned on a Friday: Here's what happened in between.

Wednesday, Sept. 25

12:39 p.m.: Megabus up to New York

This Greyhound offshoot -- their measured corporate response to the rise of the inexpensive Chinatown bus lines that began proliferating in the early 2000s -- is relatively pleasant and cheap (if you book it early enough, you can get round trip from Philly for $24, which wouldn't pay for your first half-hour of parking in Manhattan). They offer free WiFi, and about every fifth trip or so, it actually works. Today, I get lucky and log on easily, which helps. As a bonus, the bus takes you to 27th Street and 7th Avenue, which is an easy walk to grab the 1 train up to Lincoln Center, where all the press screenings are held.

4:18 p.m.: Walter Reade Theater

For most screenings at the NYFF, I plan to get in line about 75-90 minutes early (as with all press screenings everywhere now, it's first-come, first-serve, unless you are blessed with a blue-bordered priority badge and can skip in line about 15 minutes before the screening begins -- sadly, I'm not afforded that luxury). For Varda by Agnés, I wouldn't think I'd need to be here more than an hour early, but with little else to do, I go and sit in line now. At least I'm number one. This is a far cry from Friday morning's screening of The Irishman, which starts at 9 a.m. My plan is to be there at 7 a.m., God help me.

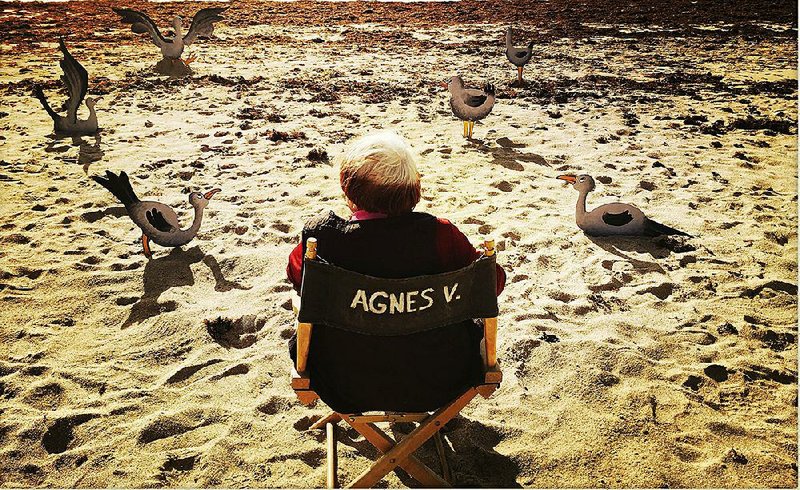

6 p.m.: Screening of Varda by Agnés

A playful sort of doc/retrospective from the much venerated French auteur and visual artist, who died in March, the film takes the form of one of her various speaking engagements (it opens with a crowd sitting in an ornate theater, with a director's chair bearing her name -- "Agnes V." -- in the foreground), with footage of several of these talks intercut with her own philosophical musings on her work, and the evolution of her branching out into other forms of art. The effect is beguiling, a celebrated artist suggesting some of the thought process behind her best-known films (she explains the interplay of "subjective" versus "mechanical" time in Cleo from 5 to 7), as well as her earliest works. What comes through most clearly is her open curiosity, and her tremendous generosity of spirit, the two most prominent reasons for her success. Her assessment of the cinematic language is fascinating, if a bit truncated, with so much ground to cover, and the later installation works she developed in the latter years of her life are also quite wonderful. Through it all, you get the sense of how she was able to fit in so unobtrusively through other peoples' lives, as she explains how she once filmed a Black Panther protest as a kindly, little lady discreetly holding a camera. It's an absorbing vision of the life of an artist, perhaps made even more accessible by the nature of her craft.

Thursday, Sept. 26

10 p.m.: Screening of Kelly Reichardt's First Cow

As a filmmaker, Kelly Reichardt's eye always seems to flit about, capturing small details -- a water ripple here, a particular scuff mark on a waistcoat there -- that lend to her films a certain kind of inexpressible poetry. In an age of speed and brevity, her frame slows everything down and forces you to take it all in. She is especially adept at finding such textures and details in the natural world, so her new film, which offers a brief modern prelude before plunging us back into the 1840s, as a gentle-souled man known as "Cookie" (John Magaro) working as a cook for a brigand outfit of fur traders in the Oregon territory, picks mushrooms in a densely wooded glade. He comes to meet King Lu (Orion Lee) as the Chinese businessman on the run hides naked behind some ferns. The two strike up a friendship -- rare enough, we are to understand, in these harsh parts -- and eventually come to craft a risky yet lucrative business, whose lifespan is extremely limited. Despite the callousness of the male-dominated society (which Reichardt happily typifies with the grunting ogres she uses to populate the small villages and forts around them), the film is actually more gentle, tonally, than much of her previous work, largely because of the temperate nature of the two friends, especially Cookie, who never quite seems of this particular world. We know how things end from the early minutes on, but as a testament to Reichardt's skill, when it happens, it still comes as a surprise, a slight undulation in a spider's web hosted between a pair of pines.

1:15 p.m. Screening of Pedro Almodóvar's Pain & Glory

Having garnered extremely positive reviews from Cannes and the Toronto International Film Festival, Almodóvar's latest has some calling it a "return to form" for the Spanish director, but as others have pointed out, he has been making these sorts of mature and melancholic films for the last decade. Early in his career, his films had a burst of cheek, a kid trying to prove what kind of naughty boy he could be, but those days of riotous farce and scatological humor seem far behind him now. Antonio Banderas plays Salvador Mallo, a director of some renown who has been locked up tight, both by his increasing physical discomforts, and by his emotional trauma after the passing of his dear mother (as a young woman, played by Penelope Cruz, and as an elderly woman by Julieta Serrano). Rightly enough, it has been compared to Fellini's 8 ½, another film about a famous director stuck on a lonely island of creative fallowness, but interestingly Almodóvar never indulges in Fellini's more surreal flights of fancy. Instead, he keeps Salvador's memory path straightforward -- early life episodes that eventually begin to gather into something more cohesive -- in such a way as to show a different sort of creative process at work. It's not the genius of 8 ½, but there's a serious maturity in not attempting to ape that masterpiece. Almodóvar's film stands on its own just fine.

Friday, Sept. 27

5:30 a.m. Early Wake-up Call

I'm bleary, having stayed up late watching my Eagles barely beat a tough Packers squad in Green Bay, but by rough estimate, every film critic, programmer, entertainment journo and executive will be arriving early in line for the day's big headliner, so I can't afford to make a mistake.

6:51 a.m.: Arrive at Lincoln Center

Breathlessly, I hop out of the train, fly up the steps of the 66th Street subway station, and walk-jog across Broadway, to finally arrive in front of the Alice Tully Theater, where I am ... fifth in line. Mayhap I was a little paranoid?

9:10 a.m.: Screening of Martin Scorsese's The Irishman

In a sense, Scorsese -- the director of Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Goodfellas and Casino -- making a mob-related film starring Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci, is fighting against his own legacy. And certainly parts of the film in the early going feel almost rote, even with the multi-layered time jumps (controversially covered via anti-aging CGI, see below), but by the time Al Pacino shows up as the infamous, all-powerful Jimmy Hoffa, the president of the teamster's union, things pick up, and by the end, with De Niro's character sitting by himself in a nursing home, alone and lonely, contemplating his end with regret and remorse, the film takes on a dimension that does feel new to Scorsese's well-established form. It isn't as nimbly inspired as some of his best earlier work, but as it happens, that quality adds a pathos to the whole enterprise. It has the feel of a eulogy, a place to put the ashes, as De Niro's character contemplates near the end. The last round-up of a legendary group of performers and artists. It's indeed long at 3 hours and 29 minutes, but you can understand why they would want to hold onto the moment as best they can. It has been 24 years since De Niro, Pesci and Scorsese all worked together, and you get the sense this will likely be the last.

MovieStyle on 10/11/2019